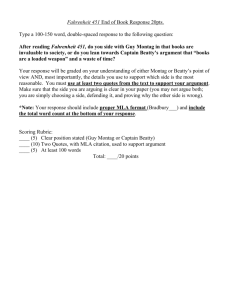

The Hunger Games/ Fahrenheit 451

advertisement