Lesson 70

advertisement

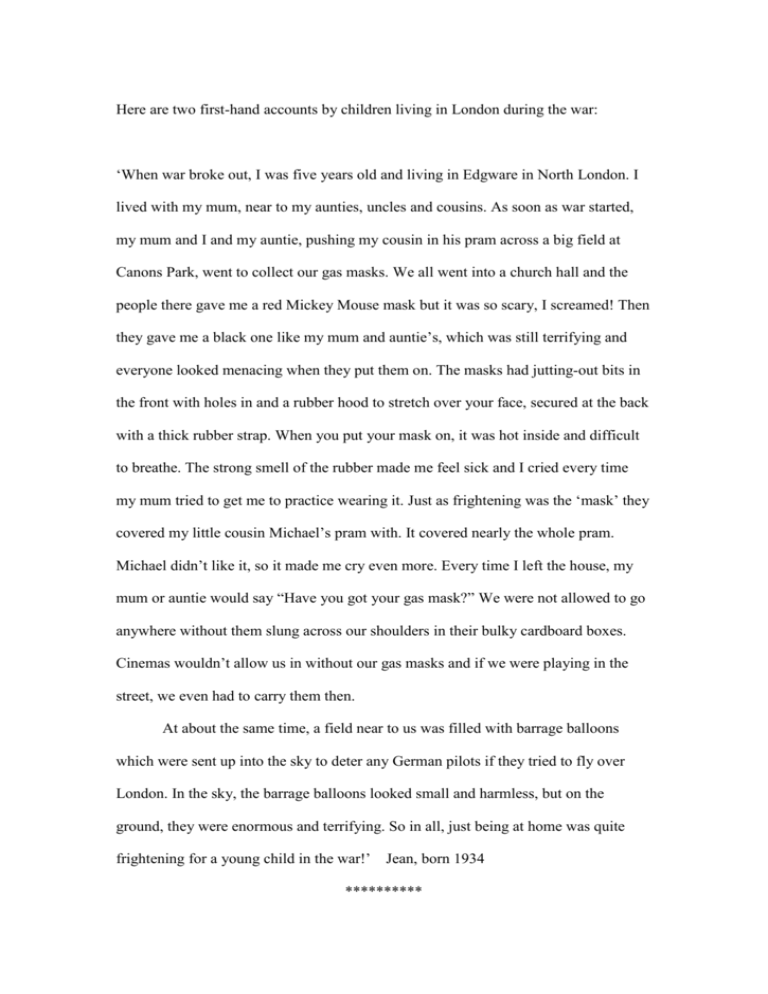

Here are two first-hand accounts by children living in London during the war: ‘When war broke out, I was five years old and living in Edgware in North London. I lived with my mum, near to my aunties, uncles and cousins. As soon as war started, my mum and I and my auntie, pushing my cousin in his pram across a big field at Canons Park, went to collect our gas masks. We all went into a church hall and the people there gave me a red Mickey Mouse mask but it was so scary, I screamed! Then they gave me a black one like my mum and auntie’s, which was still terrifying and everyone looked menacing when they put them on. The masks had jutting-out bits in the front with holes in and a rubber hood to stretch over your face, secured at the back with a thick rubber strap. When you put your mask on, it was hot inside and difficult to breathe. The strong smell of the rubber made me feel sick and I cried every time my mum tried to get me to practice wearing it. Just as frightening was the ‘mask’ they covered my little cousin Michael’s pram with. It covered nearly the whole pram. Michael didn’t like it, so it made me cry even more. Every time I left the house, my mum or auntie would say “Have you got your gas mask?” We were not allowed to go anywhere without them slung across our shoulders in their bulky cardboard boxes. Cinemas wouldn’t allow us in without our gas masks and if we were playing in the street, we even had to carry them then. At about the same time, a field near to us was filled with barrage balloons which were sent up into the sky to deter any German pilots if they tried to fly over London. In the sky, the barrage balloons looked small and harmless, but on the ground, they were enormous and terrifying. So in all, just being at home was quite frightening for a young child in the war!’ Jean, born 1934 ********** ‘In 1939, I was 11 and living in Hackney, London. One day in September, my Headmaster told us we were going to be evacuated. The next day, my mum took me to Liverpool Street station where everyone from my school was gathering with their mothers. All the mothers were crying, which was upsetting as we didn’t know where we were going or when we’d see our families again. We had our gas masks over our shoulders, a small bag of belongings and a label tied to our coats. My label had my name and school written on it. The train took us to a place called Upwell near Wisbech in Cambridgeshire and we were all ushered into a hall, where we stood while several local ladies chose who they wanted to take home. Once they had gone with the other children, the children who were left were rounded up by other ladies who took them off in their cars. After the whole school had gone, my friend and I were left on our own as no one had chosen us, probably because we were tall for our age, so the ladies probably thought we’d eat more than the others. Eventually, one lady came back and drove us to a chicken farm. The house was smelly and dilapidated and the woman who opened the door scowled when she saw us. “I don’t want boys!” She shouted. “I said I wanted girls!” But the woman who had driven us told us she had no choice and left us there. We had to share a bed and were bitten by fleas. In the morning, the woman asked us if we ate crab paste sandwiches. Not wanting to be difficult, we both nodded. From then on, for every meal, she gave us crab paste sandwiches. During the day, we went to school in a local hall, where all our old teachers were, but I was dreadfully homesick. I wrote to my mother to come and get me. Before the war, I had begged her for a bike for my birthday, so I wrote and said if she came for me, I didn’t want a bike. That made her realise how unhappy I was and turned up the next day, but my Headmaster said that if I went back home with her, I would never be allowed back to that school. I never saw him again.’ Stan, born 1928