Qual-Quant Session RR-SoTL 2014

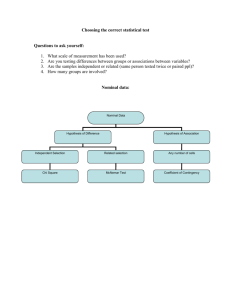

advertisement

Educational research, assumptions, and contrasting with research in the sciences Quantitative Data Analysis: ◦ Types of Data and Statistics Qualitative Data Analysis: ◦ Definitions and Coding “Hard” knowledge Produce findings that are replicable Validated and accepted as definitive (i.e., what we know) Knowledge builds upon itself– “skyscrapers of knowledge” Oriented toward the construction and refinement of theory “Soft” knowledge Findings based in specific contexts Difficult to replicate Cannot make causal claims due to willful human action Short-term effort of intellectual accumulation– “village huts” Oriented toward practical application in specific contexts Descriptive Means Medians Modes Percentages Variation Distributions Inferential Draws conclusions Assigns confidence to conclusions Allows probability calculations Wang, Schembri and Hall JMBE 14:12-24 (2013) FIGURE 5. Student performance in (A) midsemester and (B) final exams across 2010 (n = 265) and 2011 (n = 264) offerings of MICR2000. FIGURE 6. Student Evaluation of Course and Teaching (SECaT) scores across 2010 and 2011 offerings of MICR2000. Students were invited to voluntarily respond to surveys regarding their evaluation of teaching within MICR2000 in 2010 (n = 108) and 2011 (n = 87) using a standardized University-Wide Student Evaluation of Course and Teaching (SECaT) survey instrument. Student responses corresponded to a 5 -point Likert scale and quantified as follows: 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree. Bars represent mean +/– standard error of the mean (SEM). *Denotes a statistically significant difference between student responses for 2010 and 2011 offerings of MICR2000, as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test (p < 0.05). Wang, Schembri and Hall JMBE 14:12-24 (2013) Nominal Categorical No mean ● Education level ● Gender Sounds like “NAME” Ordinal Interval Natural ordering Extends ordinal data Unequal intervals Equal intervals ● Rankings ● Temperature ● Survey data ● Time Sounds like “ORDER” Sounds like what it is Borgon et al., JMBE 13:35-46 (2013) Hurney JMBE 13:133-141 (2012) Boone and Boone Journal of Extension 50:2TOT2 (April 2012) Darland and Carmichael JMBE 13:125-132 (2012) Problem (Theory) Question (Hypothesis) Methods (treatment, control groups) Intervention Data (Triangulation) Conclusions Change practice One category Nominal or Ordinal (Qualitative) Type of Data Two categories Frequency, %, Goodness-offit, 𝑥 2 Frequency, %, Contingency table, Test of Association, 𝑥2 One Relationshi ps Number of Predictor s Multipl e Interval (Quantitativ e) Continuou s Measuremen t Ranks Multiple Regressi on Independent Type of Questio n Two Relation Between Groups Dependent Differences Primary Interest Spearman’ s rS Degree of Relationsh ip Pearson Correlatio n Form of Relationsh ip Linear Regressi on Independe nt samples t MannWhitney U Paired Samples t Wilcoxon Number of Groups Independent Multipl e Relation Between Groups Dependent Adapted from D.C. Howell, Fundamental Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (6th ed.) Wadsworth Cengage Learning (2008) Number of Indep. Var. Repeated Measures ANOVA Friedman One-Way ANOVA One Multipl e KruskalWallis Factorial ANOVA 1. Collect student demographic data a) Want to discover if students between treatment and control groups had the similar ethnic backgrounds 2. Collect test grades before and after intervention a) Want to see if your teaching intervention resulted in a significant difference in test scores between control and treated groups 3. Survey students on their own perceptions of learning a) Want to see if your teaching intervention resulted in a significant increase among responses to Likert-scale questions regarding student learning gains between control and treated groups Graduate school level: You have categorized your students into three performance groups; novice, developing, and expert based on high school GPA and SAT data. You want to compare the performance of these groups on a critical thinking assessment before and after your teaching intervention. Qualitative data is information which does not present itself in numerical form and is descriptive, appearing mostly in conversational or narrative form. Words, phrases, text… Hard vs. soft (mushy) Rigor Validity and reliability Objective vs. subjective Numbers vs. text What is The Truth? Lab notebooks Open-ended exam questions Papers Journal entries On-line discussions, blogs Email Twitter/ ‘tweets’ Notes from observations Responses from interviews and focus groups Qualitative analysis is the “interplay between researchers and data.” Researcher and analysis are “inextricably linked.” Inductive process ◦ Grounded Theory Unsure of what you’re looking for, what you’ll find No assumptions No literature review at the beginning Constant comparative method Deductive process ◦ Theory driven Know the categories or themes using rubric, taxonomy Looking for confirming and disconfirming evidence Question and analysis informed by the literature, “theory” Why do faculty leave UW-Madison? Do UW-Madison faculty leave due to climate issues? Coding process: ◦ Conceptualizing, reducing, elaborating and relating text– i.e., words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs. Building themes: ◦ Codes are categorized thematically to describe or explain phenomenon. Read through the reflection paper written by a student from an Ecology class and highlight words, parts of sentences, and/or whole sentences with some “code” attached and identified to those sections. Why? Read through this reflection paper and code based on this question: What were the student’s assumptions or misconceptions before taking this course? Why? Read through this reflection paper and code based on this question: What did the student learn in the course? Why? Why or why not? Use mixed methods, multiple sources. Triangulate your data whenever possible. Ask others to review your design methodology, observations, data, analysis, and interpretations (e.g., inter-rater reliability). Rely on your study participants to “member check” your findings. Note limitations of your study whenever possible. • • • • Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, Creswell, J.W., and Plano Clark, V.L., 2006, Sage Publications. Discipline-Based Education Research: A Scientist’s Guide, Slater, S.J., Slater, T.F., and Bailey, J.M., 2010, WH Freeman. “Educational Researchers: Living with a Lesser Form of Knowledge,” Labaree, D.L., 1998, Educational Researcher, 27(8), 4-12. Software Atlas.ti and Nvivo cmpribbenow@wisc.edu