data driven research

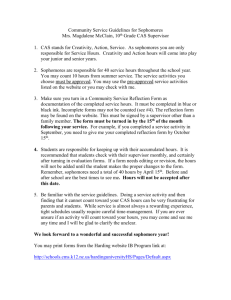

advertisement

Running head: SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS School Engagement Support From After School Programs: Effects On GPA And Attendance For Sophomore Students Nick Yoder Portland State University SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Literature Review Method 4 11 Participants 11 Materials 12 Procedure 14 Results 15 Discussion 17 Conclusion 20 References 21 Appendices 24 Appendix I: Parent Letter 24 Appendix II: English Teacher Guide 25 Appendix III: Student Script 26 Appendix IV: Centennial After School Programs 28 Appendix V: SUN Form 31 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 3 Abstract The purpose of this study was to assess if students who participated in after school programs would have a greater school engagement through increased attendance and grade point averages. 76 sophomore students with fewer than six credits beginning the school year were introduced to after school programs through a school counseling intern. The students were given a number of activities to participate in. In addition, the parents/guardians of the student were notified of the opportunity through a letter and a phone call. Students were tracked through the intervention to see if grade point average or attendance varied during the intervention. This research did not show a significant correlation between attending an after school program and greater school engagement. This study can be a starting point for others looking to improve school engagement with students. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 4 Introduction Recently, there have been numerous studies connecting involvement in after school programs to positive academic achievement and social development. Several studies have pinpointed what types of after school programs have been effective at working with different groups of students. School engagement in this study will be linked to grade point average and attendance levels. When browsing the research, the majority of studies focus on freshmen and senior students. Also in schools, there is a trend of counselors working more with these groups more than sophomores or juniors. Sophomores particularly are often not targeted and therefore lose relationships with adults in the school. If the students are not motivated to succeed, the possibility to fail is greater and the likelihood of dropping out increases. Education in the United States is using data more frequently to support changes aimed at student success. Student success may have looked different over the years, but currently, pressure for success lands in two specific categories; graduation rates and standardized test scores. As the importance of these measures increases, it is the challenge of the schools and school districts to find ways to improve student success. Numerous barriers are found in the way of student success. As poor attendance (National Center for Education Statistics, 2009), drug and alcohol use (Eccles, Barber, Stone & Hunt, 2003), lack of supervision (Fredricks & Eccles, SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 5 2006), lower socioeconomic status (Lamdin, 1996), or simply lagging skills become more prevalent, student success becomes limited. This is found in worsening grades or even failing courses, which can lead to dropping out of high school (Mahoney & Cairns, 1997). Poor attendance at school has been a problem for many years (Lamdin, 1996)(Steward, 2008). As student absences increase, regardless of excused or unexcused, standardized test scores (Gottfried, 2009) and Grade Point Averages (Steward, 2008) decrease. In 2008, 20% of students were absent from school for 3 or more days in the previous month (National Center for Education Statistics, 2009). This leads to a lack of curriculum specific content, as well as a decrease in social connectivity. This affects students in any grade level but the largest impact is to students in a lower socioeconomic status (Lamdin, 1996). Mahoney & Cairns go on to say that some students may dropout of school because of a lack of “maintenance and enhancements” of positive characteristics (1997). The thought follows that without strengthening the positive aspects of students, they are destined not to graduate. There is a true need for strengthening these connections with students and school (1997). Some ways to strengthen connections with students and school are extracurricular programs. These programs are various adult-sponsored activities that fall outside the normal school curriculum and can include various schoolbased activities, community organizations, or youth development programs (Bohnert, Fredricks, & Randall, 2010). These programs can occur before or after school and on the weekends and are called after school programs, which is what SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 6 this study will focus on. Most of these extracurricular activity programs are structured in a way to support positive peer interactions and the development of social skills and values (Fredricks & Eccles, 2006). One main benefit to involvement in after school programs are school clubs or sports are structured in a way that leads to peer interactions and developing friendships in a greater capacity than does the traditional classroom contexts (Fredricks & Simpkins, 2013). Bohnert, Fredricks, & Randall also concert the success of after school programs can depend on the age and culture of the students (2010). Although program quality is the critical framework for recruitment, participation, and retention (Lauyer & Little, 2005), students vary on which activities they engage. African American youth tend to participate more in sports, church-based activities and varied after school programs than in student government or citizenship activities (Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012). Latino students will often rely on trusted friends and institutions like the church for their after school programs (2012). Another interesting aspect finds students who reported that between activities, the ones which participants engaged with both peers and adults, as opposed to only peers or only adults, were the most motivating (Shernoff & Vandell, 2007). Not all students will join after school programs but those that do may see numerous positive outcomes. Durlak, Weissberg, & Pachan found students who were invested in these programs had positive outcomes in feelings and attitudes, various “indicators of behavioral adjustment,” and school performance (2010). SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 7 The indicators of behavioral adjustment resulted in fewer behavior problems at school and with peers (2010). Some behavior changes include the use of drugs and alcohol. Adolescents involved in after school programs in 10th grade reported less involvement with drinking alcohol and using drugs (Eccles, Barber, Stone & Hunt, 2003). Although involvement in sports has shown an increase in participants drinking alcohol levels, it has also shown that they like school more, had a higher Grade Point Average, and were more likely to attend college than nonparticipants (2003). These findings showed a decreased as both “jocks” and “brains” accounted for less drug and alcohol use when enrolled in an activity (2003). “Risky” behaviors are less likely when students are engaged and value their after school program (Fredricks & Eccles, 2010). In addition to reducing problematic behavior, many studies show numerous positive outcomes and prosocial gains made by students involved in after school programs. Students involved in after school programs, regardless of social class, gender, or intellectual aptitudes were more likely to have better educational outcomes (Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003). Academic benefits to students are numerous in several ways. Students involved in programs showed an increase in attendance and academic performance (Mahoney & Carryl, 2005). Over the years, this has resulted in decreasing rates of early school dropout rates in boys and girls (Mahoney & Cairns, 1997). Schools and administrators are consistently looking to improve these numbers. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 8 Students themselves reported being “more adjusted” after graduation than peers who did not participate in after school programs (Fredricks & Eccles, 2010). These activities help develop friendships among diverse peers, especially in supporting interracial friendships (Moody, 2001), that may be unlikely to develop within “normal” circumstances (Fredricks & Eccles, 2006). In fact, Mahoney, Cairns, and Farmer reported that students who were involved for two or more years of after school programs during adolescence were associated with higher educational aspirations and interpersonal competence by twelfth grade and two years after (2003). Though much of this data illustrates student gains, personal views on after school programs and the incentive to join them, still varies greatly. In the US, participation in after school programs is a normal experience (Bohnert, Fredricks & Randall, 2010). Schools around the country will offer programs varying in size, shape, scope and more (Denault & Poulin, 2009). Because of the variety of these programs, students have the ability to find a program that fits their interests. However, not all students participate consistently or even at all. Fredricks and Simpkins illustrated that because activities are voluntary settings and that youth select them (2012), it is beneficial to understanding the rationale behind joining them. There are a handful of reasons that students join after school programs. While difficult to determine how much one of these reasons effects an individual, looking at the variety can influence decision-making. Lauyer and Little determined that there were three key features to joining a group: developing a SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 9 sense of community in safety, committed program staff, and challenging, age appropriate, and fun activities (2005). Some students choose after school programs to foster relationships. Denault and Poulin reported that many students join an activity because they have friends involved in the program (2009). Being with friends and making new friends are primary motives for joining and staying in organized activities (2009). Other students choose sports and athletics for after school programs. This is higher than fine arts in youth through sixth grade (2009). However, in upper grades, the percentage drops when a need for higher skills increases. (2009). This allows for other opportunities as students reach high school. Ultimately, each voluntary activity can be personally expressive (Barber, Eccles, & Stone, 2001) and can be a distinct learning environment with opportunities for growth and development (Fredricks & Eccles, 2010). Although after school programs are mostly voluntary, many students depend on parents or guardians to help them either enroll or attend the activities. Some schools provide transportation to and from home for programs in the morning or after school. Without parent support, many of these programs cannot be participated by the student. In addition, parents’ beliefs about organized activities predict higher rates of participation, including sports (Denault & Poulin, 2009). If parents don’t see value in a program, they may not encourage their student to enroll. Matching program content and scheduling to students needs can help alleviate this concern (Lauyer & Little, 2005). This isn’t always practical, but can be looked at by program developers. In addition, staff can emphasize how the program will help youth develop skills needed for workplace or college, SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 10 which may get families on board (2009). When trying to enroll students, Lauyer and Little describe the importance or reaching out directly to families through phone calls and community outreach (2005). Ultimately, parents are important in the after school program process and support will benefit the student and the program greatly. At Centennial High School, a general education high school located in Gresham, Oregon, school counselors have goals set for each year. The past few years, the team has focused on increasing the number of credits that freshman finish their first year and how well they have prepared juniors to be “college ready.” Currently, there are no goals set for sophomore students. However, sophomore year can be an extremely important year for students. Several studies focusing on sophomores have demonstrated that inclusion in prosocial activity predicted lower substance use, higher self-esteem, psychological adjustment, educational and occupational outcomes and increased likelihood of college graduation (Barber, Eccles, & Stone, 2001)(Fredricks & Eccles, 2010). It also has been shown that being involved can decrease the risky behaviors in 10th graders according to Eccles and Barber (1999). Working with sophomore students is extremely important if school achievement is important to counselors. Enrolling all students into an after school program has its importance, but with the counselors focusing on other age groups, the sophomore age is key to increase school engagement. The purpose of this study is to connect sophomore students to an after school program in an attempt to increase school engagement. School SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 11 engagement will be evaluated by the student’s grade point average and their daily attendance. This study will focus with a researcher working with sophomore students who have earned fewer than 6 credits prior to the beginning of the school year to encourage involvement in after school programs. The researcher will conduct one meeting with each student in which the researcher will discuss after school program opportunities. The researcher will encourage students to join a program and discuss talking with parents or legal guardians to discuss importance of after school programs. The researcher will send information on how to apply for the after school program. The researcher will then make phone call to parents/guardians describing the after school programs, the importance of joining one, and the potential positive effects for their student. Following the phone call, a letter will be mailed to the parent/guardian detailing what was discussed in the phone call. Also, instructions on how to enroll in the programs will be included. In addition, the researcher will give sophomore level English teachers a script of encouraging students to get involved in an after school program. The teacher will mention the programs three times and encourage students to enroll. This program aims to address the research question: Will participation in an after school program increase school engagement depicted by grade point average and attendance percentages? Method Participants SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 12 Participants for this research were students from Centennial High School in the Centennial District from Portland, Oregon. Minority students represent 31% of the population with 22% from the Latino heritage. 45% of students district wide are free and reduced lunch or from a family in poverty. This study will concentrate on sophomore level students who have fewer than 6.0 credits at the onset of the school year 2013-2014. A student who has 6.0 credits or more after their freshman year is considered “on track to graduate” at Centennial High School. There will be no discrimination due to gender, race, language, or otherwise. At the beginning of the school year, there were 76 of 516 sophomores currently enrolled at Centennial High School who had earned fewer than 6.0 credits. Throughout the year, 67 students continued to be enrolled at Centennial High School and received the intervention. Further information on gender, race, or SES was not collected, but can be generalized based on high school statistics. Materials Data on student achievement and attendance was gathered through a multi-district platform called Synergy. Synergy gives the information like attendance, grading, demographics, and other related information. Data was taken from this program and put into a spreadsheet file using Microsoft Excel. Grade point averages and attendance were gathered from synergy. A student Script was created for discussing the after school programs with the students (Appendix III). Students were written passes by the researcher to come down to the counseling office and meet with the researcher. The researcher was in one of three locations. Each location was a separate SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 13 counselor’s office. When students arrived, the researcher talked with the students based on the student script. From there, students were given two forms: the Centennial High School After School Programs list (Appendix IV) and a SUN Form (Appendix V). These forms were to distinguish all the possible after school programs that were offered at Centennial High School. To introduce the after school programs along with information about their importance for the students, a parent letter was created (Appendix I). This letter highlighted information about the programs and why their student would want to use this. The main component of this letter was also the script for the phone call made to parents/guardians. The letter was referenced as the researcher discussed options with the family. A script was also created for all sophomore English teachers (Appendix II). The script introduces the SUN program and other after school programs and how to apply for them. This script was emailed to all teachers and delivered to classes by the teacher. To give students a comprehensive look at all the possible after school programs available at Centennial High School, the researcher created a onepage overview (Appendix IV). This sheet was given to all students and sent home to families in a letter. The SUN program requires registration forms to begin working in their groups. The researcher gathered SUN registration forms to distribute to students and families (Appendix V). To enroll in these programs, students needed to complete a form and bring them to the SUN office. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 14 Procedure The researcher gathered names of students who had obtained fewer than 6.0 credits to begin the school year. The researcher created a script to discuss with students. In addition, a list of clubs and after school programs was created to be distributed to the students. In addition, a SUN form detailing their after school programs was collected to be distributed. The researcher created a pass for each student, which allowed them to leave class during the school day and meet the researcher in the counseling office. The student sat in one of three different counseling office rooms with the researcher. Upon entering, the researcher used the Student Script to invite students to try an after school program. The researcher handed the student copies of the After School Programs page and the SUN form. The researcher then alerted the student that a phone call and a letter would follow informing families of the programs. Once a student had met with the researcher, a letter was sent to the families of the student. The letter included information about the after school programs and the conversation that took place between the researcher and the student. It also alerted parents that a phone call would follow. Approximately a week after a letter was sent home, the researcher made phone calls to the families of the students. A script was followed to discuss the meeting with the student and to clarify the after school programs importance. Two weeks after beginning meeting with students, the researcher spoke to sophomore English teachers about reading a note from the school counselors. An email with a script for the English teachers followed. The script gave teachers SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 15 the ability to talk to their students about the after school programs. All sophomore students at Centennial High School were able to hear this message. Six weeks later, the researcher met with the leaders of Centennials after school programs. The researcher was able to get names of students who had joined a program over the previous weeks. This information was recorded with the student information. Results Through the end of the intervention, 61 students (N=61) were still enrolled at Centennial High School. Sixteen students from the beginning of the study and six students left from the time they first met with the researcher and the end of the study. Those students were not included in the statistics. The intervention group was listed as group 1. Nineteen students (N=19) began participating in an after school program. Group 2 were forty-two students that did not participate (N=42) in an after school program. Students who became involved in an after school program showed some gains on both grade point average (GPA) and attendance. The means of both groups were calculated before the intervention and 6 weeks later, after the next grading period. Means GPA Attendance % Pre Intervention Programs (N=19) No Programs (N=42) Programs (N=19) No Programs (N=42) Post Intervention 1.278 1.331 1.409 0.849 1.111 0.854 0.782 0.645 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 16 An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare change in grade point average for being in an intervention and not being in an intervention. There was not a significant difference in the scores for students in an intervention level 1 (M= .1227, SD = .71802) and level 2 (M= -.0998, SD = .07535) conditions: t (25.824)=1.228, p=.230. These results suggest that an after school programs don’t have an effect on grade point average. GPA Group Statistics Intervention GPA diff N Mean Std. Deviation Std. Error Mean 1.00 19 .1227 .71802 .16472 2.00 42 -.0998 .48832 .07535 Independent Samples Test Levene's Test for Equality of Variances t-test for Equality of Means 95% Confidence Interval of the Sig. (2- F GPA Equal diff variances Sig. 4.585 .036 t 1.416 df tailed) Mean Difference Std. Error Difference Difference Lower Upper 59 .162 .22252 .15713 -.09189 .53694 1.228 25.824 .230 .22252 .18114 -.14994 .59498 assumed Equal variances not assumed An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare attendance for being in an intervention and not being in an intervention. There was not a significant difference in the scores for students in an intervention level 1 (M= SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 17 .1447, SD = .11534) and level 2 (M= .3476, SD = .23808) conditions: t (58.631)=4.481, p=.0001. These results suggest that an after school programs don’t have an effect on attendance. Attendance Group Statistics ATT dur Intervention 1.00 2.00 N Mean Std. Deviation .1447 .11534 .3476 .23808 19 42 Std. Error Mean .02646 .03674 Independent Samples Test Levene's Test for Equality of Variances t-test for Equality of Means 95% Confidence Interval of the Sig. (2- F ATT Equal dur variances 6.444 Sig. t df tailed) Mean Std. Error Difference Difference .014 -3.520 59 .001 -.20288 .05763 -4.481 58.631 .000 -.20288 .04527 assumed Difference Lower .31820 Upper -.08756 Equal variances not .29349 assumed Discussion The results of this test suggest that there is not a significant difference between students who attend after school programs and those who don’t having higher school engagement. Because the data does not support higher increases in grade point average or in attendance, it may be chance that being in an after school program can contribute to school engagement. -.11228 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 18 Although there is not significant support for school engagement, the mean of GPA for students enrolled in an after school program rose from 1.278 to 1.331. In the group of students who did not participate in after school programs, the mean of GPA fell from 1.409 to 1.111. This may not be statistically significant, but as an educator, helps show there may be some relation to school engagement. Attendance seemed to increase slightly for students involved in a program. This can be for a number of factors. Attendance is a chronic issue for students in schools and though after school programs have shown an ability to increase attendance, students recently began their program and may not have been as connected to it as students depicted in other studies. Students without a program may be continuing an attendance pattern in a negative outcome. One limitation of this study, is that although the script was made to work with students and families, there was some variance in the conversation. However, this may be the case with most research in the school settings, as there is no control that would be the same for everyone. Another limitation to be noted is that this intervention had only several weeks before data could be completed. Although there is hope that these interventions can support students needs, it’s important to remember that RTI process can be a long term plan and not a quick solution (Shinn, 2007). In a normative RTI process, goals are typically set for 6-12 weeks and students are assessed once or twice a week (Shinn, 2007). It would be prudent to have more time for these interventions to take effect. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 19 In addition, because of timing issues, the research could not begin until 2 weeks before the end of a grading period. This meant that grades at the end of the semester didn’t have a chance for students to get participating in an activity. For the beginning of the new semester, grades may not have truly reflected a student’s sense of importance. Results may look differently if given a longer window for the intervention. Beginning the school year with these interventions may have shown more drastic results. Also, grades after the first six weeks of a grading period may not accurately portray students eventual grade. There may not have been as many assignments at the beginning and most are not as cumulative as later in the semester. It seems that along with many interventions, it may be prudent to insist on more meetings with students. Students who form relationships with adults may be more likely to follow advice given. Hence, if a counselor would meet more frequently with these students, there may be a likelier chance of getting students involved in more after school programs. Furthermore, the researcher had very little prior knowledge of the students involved in the study. It is likely that in a normative school environment, the counselors may have worked with the students before and have built a relationship. If this relationship exists already, it may have more likelihood of success. Also, working with families will improve if there is already communication built up. The researcher did not have translated letters or phone calls ready for families who were non-English speakers. Having translations ready would have SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 20 been effective for helping families understand what was being offered to their students. Several families could not get the support from the researcher due to a lack of communication effectiveness. Conclusion There is more research to be done on these topics. Throughout school districts around the country, there are students who are struggling to pass classes and attend school on a consistent basis. As schools become increasingly accountable to students well-being, it will continue to need approaches to work with students and families who are struggling. By connecting students to other school functions, it may help serve needs that are currently unmet by the school itself. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 21 References Barber, B.L., Eccles, J.S., & Stone, M. R. (2001). Whatever happened to the jock, the brain, and the princess? Young adult pathways linked to adolescent activity involvement and social identity. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 429-455. Bohnert, A., Fredricks, J., & Randall, E. (2010). Capturing unique dimensions of youth organized activity involvement: theoretical and methodological considerations. Review of Educational Research, 80 (4), 576-610. Denault, A., & Poulin, F. (2009). Predictors of adolescent participation in organized activities: a five-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19 (2), 287-311. Durlak, J., Weissberg, R., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 294-309. Eccles, J., & Barber, B. (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: what kind of extracurricular participation matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 10-43. Eccles, J., Barber, B., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59 (4), 865-889. Fredricks, J., & Eccles, J. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42 (4), 698-713. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 22 Fredricks, J., & Eccles, J. (2010). Breadth of extracurricular participation and adolescent adjustment among African-american and European-american youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20 (2), 307-333. Fredricks, J., & Simpkins S. (2012). Promoting positive youth development through organized after-school activities: taking a closer look at participation of ethnic minority youth. Child Development Perspectives, 6 (3), 280-287. Fredricks, J., & Simpkins, S. (2013). Organized out-of-school activities and peer relationships: Theoretical perspectives and previous research. New Directions For Child and Adolescent Development, 140, 1-17. Gottfried, M. (2009). Excused versus unexcused: how student absences in elementary school affect academic achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31 (4), 392-415. Lamdin, D.J. (1996). Evidence of student attendance as an independent variable in education production functions. The Journal of Educational Research, 89 (3), 155-162. Lauver, S., Little, P. (2005). Recruitment and retention strategies for out-ofschool time programs. New Directions for Youth Development, 105, 71-89. Mahoney, J. L., & Cairns, R. B. (1997). Do extracurricular activities protect against early school dropout? Developmental Psychology, 33, 241-253. Mahoney, J.L., Cairns, B.D., Farmer, T. (2003). Promoting interpersonal competence and educational success through extracurricular activity participation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 409-418. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 23 Mahoney, J.L., & Carryl, E. (2005). An ecological analysis of after-school program participation and the development of academic performance and motivational attributes for disadvantaged children. Child Development, 76 (4), 811-825. Moody, J. (2001). Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. American Journal of Sociology, 3, 679-716. National Center for Education Statistics. (2009). National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data explorer. Retrieved from Http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata No Child Left Behind Act, 20 U.S.C. § 6301 (2002). Posner, J., & Vandell, D. (1994). Low-income children’s after-school care: are there beneficial effects of after-school programs? Child Development, 65, 440-456. Shernoff, D.J., Vandell, D.L. (2007). Engagement in after-school program activities: quality of experience from the perspective of participants. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36 (7), 891-903. Shinn, M.R. (2007). Identifying students at risk, monitoring performance, and determining eligibility within response to intervention: Research on educational need and benefit from academic intervention. School Psychology Review, 36, 601-617. Steward, R. (2008). School Attendance Revisted. Urban education, 43 (5) 519536. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 24 Appendix I: Parent Letter Dear Parents and Families, I’m writing to inform you and your student about some new opportunities at Centennial High School. As I’ve shared with your student during a previous meeting, there are many great benefits that may await your student. Your student has currently earned fewer than 6 credits for their freshman year. The counselors at Centennial High School have discovered that this may contribute to graduating later than expected or perhaps dropping out entirely. It is our expectation, that all students have the resources to graduate on time. In various research studies, students who have enrolled in after school programs have increased their academic achievement, improved attendance, and reduced the likelihood of participating in drugs and alcohol. Much of this can be linked to students finding peers who may share their beliefs and also being actively engaged in something positive after school. To help engage your student into the school culture, we hope that we can encourage your student’s participation in an after school program. After meeting with your student, there may be some programs that interest them and you approve of. Attached you will find a list of Centennial after school programs including those run by Impact Northwest’s SUN program. Participation by your student is completely voluntary on your part. Please consider joining one of the after school programs. If there are any other questions, concerns or comments, don’t hesitate to ask as I’ll be following up with a phone call in the coming days. We hope to hear from you soon, Nick Yoder Centennial High School Counseling Intern Portland State University Student SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 25 Appendix II: English Teacher Guide Everyone, I have a quick note from the counseling office about signing up for after school programs. I know some of you are involved in after school activities but those of you who aren’t may want to hear this. “New after school programs are starting soon so get on the act of finding one that fits your needs. Basketball, wrestling, cheerleading and swimming are starting soon, so meet your coaches as soon as possible. For the new SUN program, check in with your counselor or Mr. Beech, the SUN coordinator. Tutoring, fitness, careers and more are offered daily. See your counselor for more information.” Ladies and Gentlemen, it’s really important that you try and get involved in one of these activities. It can help improve your grades and you may find something that you really enjoy. I highly recommend finding one that you like. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 26 Appendix III: Student Script Researcher talking points: 1. Go over GPA and Attendance a. Check for accuracy b. Empathic questions and support c. Check on after school activities 2. Go over after school programs benefits a. Are you aware of some of the possible benefits of after school programs? There are a lot of things that have been shown to help students get better grades and be at school more. I know as you’ve said (reference previous information) you could use more support in this subject or that. Have you thought about joining one of the clubs our school offers. Here is a list. (Give list of current CHS programs) Are any of these programs interesting to you? Can I tell you about them (tell or discuss further any that they ask about). What I’d like to do, is talk to your parents/guardians about enrolling you in one or more of these programs. I’ll tell them about the benefits and how I believe it can be beneficial for you to be involved in some of these. I’ll also send home a letter detailing these options and how to enroll. Then if they are ok with things, they can sign you up. Does that sound ok? Thanks for meeting with me and I hope you give these a chance. Feel free to stop in and talk with me on SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 27 Wednesdays and Thursdays or to your counselor any day. Thanks again, bye. SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 28 Appendix IV: After School Programs form After School Programs at CHS Description Advisor CHS Clubs Aerie Band Bicycling Club Choir Close Up Club Earth Club Electric Car Club FBLA: Future Business Leader of America Gay Straight Alliance Golf Club A student-produced publication that accepts poetry, prose, illustrations, and photos. Be a part of every activity through the CHS band Learn safe cycling skills while enjoying the beautiful outdoors Several choir groups are available to interested students Visit nation’s capital while earning CHS credit Dedicated to making CHS environmentally friendly school Fabricate and race student electric car creations Learn and compete in business related fields including marketing, business creation and accounting Dedicated to creating a safe environment in schools free from discrimination, violence and harassment Work on your game all year long with the CHS swing doctor Generate awareness about the human trafficking epidemic plaguing society Human Trafficking Awareness Club MeChA Promote cultural pride and learn leadership skills through community activities MMA Club Phsyical fitness through mixed martial arts Skills USA An organization for students who are interested people interested in career and technical education like welding, video production, and culinary arts Speech & Learn, engage and compete in various Debate formal discussions or argument in league and state competitions Phil Huff Tim Wells Suzi Gurney Julia Voorhies Justin Rosenblad & Stand Thompson Joel McKee Mark Watts Adriann Hardin TBD Tom Young Reed ScottSchwalbach Kristin Klotter Justin Rosenblad Mark Watts and Stacie Fleck Jen Loeung & Kim Schiewe Additional Information SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS The Talon Thespian Club Yearbook Centennial’s school newspaper where student writers learn journalistic skills by publishing monthly editions A student led group interested in every aspect of drama Plan and design every aspect of the CHS yearbook including photography, writing, sales and distribution 29 Shelbi Wescott Kellie McCarty Shelbi Wescott Athletics Fall Football Boys/girls Chris Knudsen Cross Country Boys/Girls Greg Letts Volleyball Girls Rob Olson Soccer Boys/Girls Dance Team Cheerleading Boys/Girls Boys/Girls B: Justin Rosenblad G: Kelsey Birhofer Annie Ellett Carly Lofting Waterpolo Boys/Girls Rod Lundgren Varsity, JV, and Freshmen Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity and JV teams Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity Winter Basketball Boys/Girls Wrestling Boys/Girls B: Tim Roupp G: Jeff Stanek Roger Matthews Cheerleading Boys/Girls Carly Lofting Swimming Boys/Girls Rod Lundgren Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity and JV teams Varsity Track Boys/Girls Softball Baseball Golf Girls Boys Boys Greg Letts & Luke Franzke Steve Baker TBD Tom Young Varsity, JV, and Freshman teams Varsity and JV Varsity and JV Varsity Mr. Christy Monday – Thursday Spring SUN Basketball Open Start your day off with a basketball Gym workout in the gym SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS Tutoring Study Skills Career and College Exploration Hip Hop Dance Fitness Photography Computers Homework Club Zumba Ceramics 30 Get assistance completing homework or help in a specific subject from National Honor Society students Learn new skills and techniques to help you study for any subject Explore career opportunities and learn about the world of manufacturing Mr. Beach Tuesday & Thursday Mr. Huff Tuesday & Thursday Monday & Wednesday Learn a variety of dance techniques and movements Participate in a variety of fun and healthy ways to stay fit. Learn all the tips and techniques to taking expert photographs. Learn computer skills and navigating the web Get help completing homework or help studying for a specific subject Aerobic activity and dance to create a fun exercise experience Learn how to make pottery on the wheel Roseann Rivera Tuesday Ms. Shoda Thursday Brandon Sayrath Wednesday Melissa Wolf Wednesday Mrs. Hermann Tuesday & Thursday Monday & Wednesday CPC Welky Hoffman Michael Grubar Tuesday SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS Appendix V: SUN Form 31 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 32 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 33 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 34 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 35 SOPHOMORES ENGAGED WITH AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS 36