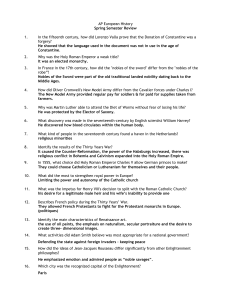

The Enlightenment offered middle-class people an intellectual and

advertisement