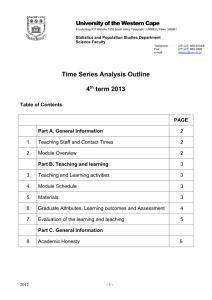

Unit 2 - University of the Western Cape

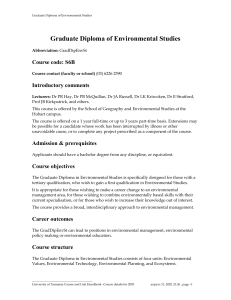

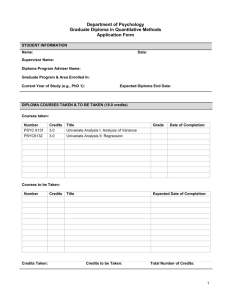

advertisement