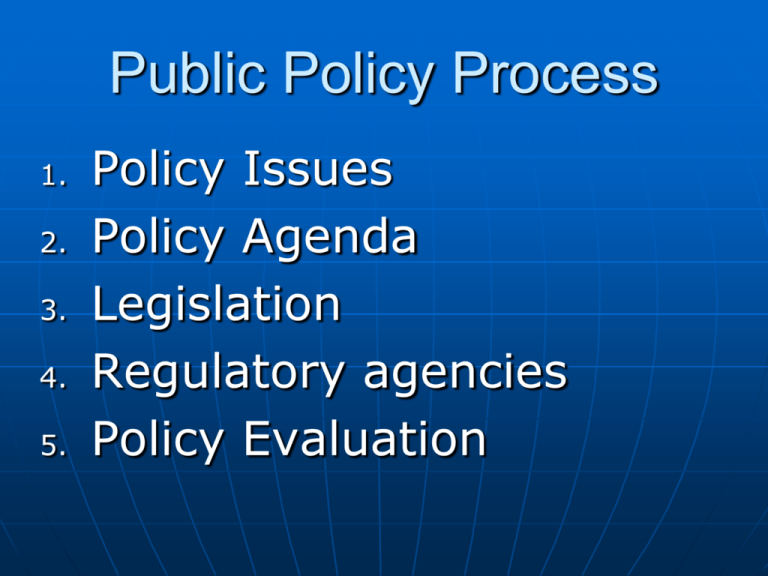

Public Policy Process

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Policy Issues

Policy Agenda

Legislation

Regulatory agencies

Policy Evaluation

Policy Issues:

Problems that exist in society

Social

Economic

Political

Technological

Policy Agenda:

Choosing which issues to focus on

Visibility

Powerful stakeholders

Important to reelection

Legislation:

Addressing the Agenda

Set parameters

Establish regulatory

agencies

Set timeframe

Regulatory Agencies:

Implement Policies

Specific rules

Penalties

Judgment

Enforcement

Policy Evaluation:

Judicial Review of Policies

Interpret laws

Order compliance

Implications of the Policy

Process Model

1.

2.

Business can bring influence at

any point in the process.

The earlier the influence is in

the process, the greater impact

and likelihood of success, and

the lower the costs will be.

Factors Affecting Current

Business/Political Relationship

•Rise in Special Interest Groups

• Decline in Voting

•Diffusion of Power in Government

Reforms in Congress

The decline of party power

Increased complexity in government

Business involvement

in politics

Lobbying

The electoral process

Lobbying:

Advocating a viewpoint to

government.

A lobbyist engages in persuasion

and gives two types of information:

• technical information.

• political information.

Lobbyists are loosely regulated.

A key issue in lobbying is the

imbalance of access and power.

.

The Abramoff Scandals

Opening Case

Rep. Tom DeLay (R-Texas) pressured lobbyists to support his

candidates and causes and rewarded the lobbyist through the

use of Congressional earmarks.

Jack Abramoff was a lobbyist whose style was to lavish

attention and favors on lawmakers.

Bob Ney (R-Ohio) accepted gifts and trips and then did

legislative favors at Abramoff’s request.

Randy “Duke” Cunningham (R-California) was corrupt to an

unprecedented degree. He even had a “bribe menu.”

Corporations dominate the political area with huge

expenditures for lobbying and campaign donations. The

recent spate of Washington scandals teach that the area in

which business must pursue its political goals can be highly

compromising.

9-3

Paths of Pressure

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

9-12

© 2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Tension Over Corporate Political

Expression

Debate is perennial over whether too much

corporate money enters politics.

Beginning with the 1907 Tillman Act, efforts

to eliminate it have been unsuccessful.

More progress has not been made due to

the tension between two strong values in

the American political system:

• Freedom of speech

• Political equality

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Efforts to Limit Corporate Influence

In 1907 progressive reformers pass the Tillman

Act, making it a crime for banks and corporations

to directly contribute to candidates in federal

elections, and this is still the law today.

After 1907 the spirit of the Tillman Act was quickly

and continuously violated.

Democrats angry at Nixon passed the Federal

Election Campaign Act (FECA) in 1971 to stiffen

disclosure requirements on campaign contributions

and expenditures.

In reaction to Watergate, Congress extensively

amended the FECA in 1974.

In 2002 in reaction to Enron and other scandals

the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act was

passed.

Citizens United (2010)

The government may not suppress

political speech based on the

speaker’s corporate identity. No

sufficient governmental interest

justifies limits on the political speech

of for-profit corporations.

Overruling Austin invalidates BCRA

Section 203 and also 2 U.S.C 441b’s

prohibition on the use of [corporate]

treasury funds.

Citizens United (2010)

We now conclude that independent

expenditures, including those made

by corporations, do not give rise to

corruption or the appearance of

corruption.

Citizens United (2010)

That the Court in NRWC did say

there is a sufficient governmental

interest in ensuring that substantial

aggregations of wealth amassed by

corporations would not be used to

incur political debts from legislators…

has little relevance here.

Citizens United (2010)

The fact that speakers may have

influence over or access to elected

officials does not mean that these

officials are corrupt.

The appearance of influence or a

access, furthermore, will not cause

the electorate to lose faith in our

democracy.

Citizens United: Dissent

The Court today rejects a century of

history when it treats the distinction

between corporate and individual

campaign spending as an invidious

novelty born of Austin…

The conceit that corporations must

be treated identically to natural

persons in the political sphere is not

only inaccurate but also inadequate

to justify this case.

Citizens United Dissent

Although they make enormous

contributions to our society,

corporations are not actually

members of it. They cannot vote or

run for office. Because they may be

managed and controlled by

nonresidents, their interests may

conflict in fundamental respects with

the interests of eligible voters.

Citizens United Dissent

The financial resources, legal structure,

and instrumental orientation of

corporations raise legitimate concerns

about their role in the electoral

process. Our lawmakers have a

compelling constitutional basis, if not

also a democratic duty, to take

measures designed to guard against

the potentially deletorious effects of

corporate spending in local and

national races.

How PACs Work

To start a PAC, a corporation

must set up an account for

contributions.

Corporate PACs get their

funds primarily from

contributions by employees.

The money in a PAC is

disbursed to candidates

based on decisions made by

PAC officers, who must be

corporate employees.

There are no dollar limits on

the overall amounts that

PACs may raise and spend.

Political action

committee

A political

committee carrying

a company’s name

formed to make

campaign

contributions.

Soft Money and Issue Advertising

In 1979 Congress amended the FECA to

encourage support for state and local political

parties by suspending limits and prohibitions

on contributions to them.

• These contributions came to be known as

soft money.

Although corporations are barred from

contributing to federal campaigns, they may

now give unlimited soft money contributions

to national party committees.

In 1996 the Supreme Court held that soft

money could be used for issue advertising.

Reform Legislation in 2002

Senators John McCain (R-Arizona) and Russell

Feingold (D-Wisconsin) pushed through a bill that

was enacted as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform

Act of 2002 (BCRA).

• National parties are prohibited from raising or spending

soft money.

• Corporations can give unlimited amounts of soft money

to advocacy groups for electioneering activity, with

restrictions during blackout periods.

• Contribution limits for individuals are raised.

• New disclosure requirements for contributions and

expenditures are introduced and penalties for

violating the law are increased.

The main purpose of the new law is to end the use of

corporate soft money for issue ads run just before

elections.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Testing the New Law

The 2004 election cycle was the first under BCRA

rules. The new law did not stop the rise in overall

spending.

• Hard money contributions went way up.

• New advocacy groups (527) formed to take in the

soft money that corporations, unions, and individuals

could no longer give to parties.

• Independent expenditures for and against

candidates increased.

So far, the new restrictions of the BCRA have

worked to cut the flow of unregulated soft money

into federal elections, but overall growth of

campaign giving and spending has not been

slowed.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Influence Process

If lawmakers or regulators accept money as a

condition for official action, they commit a

crime.

This does not mean that contributions

associated with lobbying are given for

ideological reasons with no expectation of a

return. There is a high correlation between

contribution and action.

There are other influences on representatives

apart from money, including party loyalty,

ideological disposition, and the opinions of

voters back home.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.