§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§

VITAL GUIDE TO LAW SCHOOL

How to Cater Law School

Studying Skills to Your Learning Preferences

Second Edition

By Nadya Vilá

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. For permission to distribute, please write to

NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com.

§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§

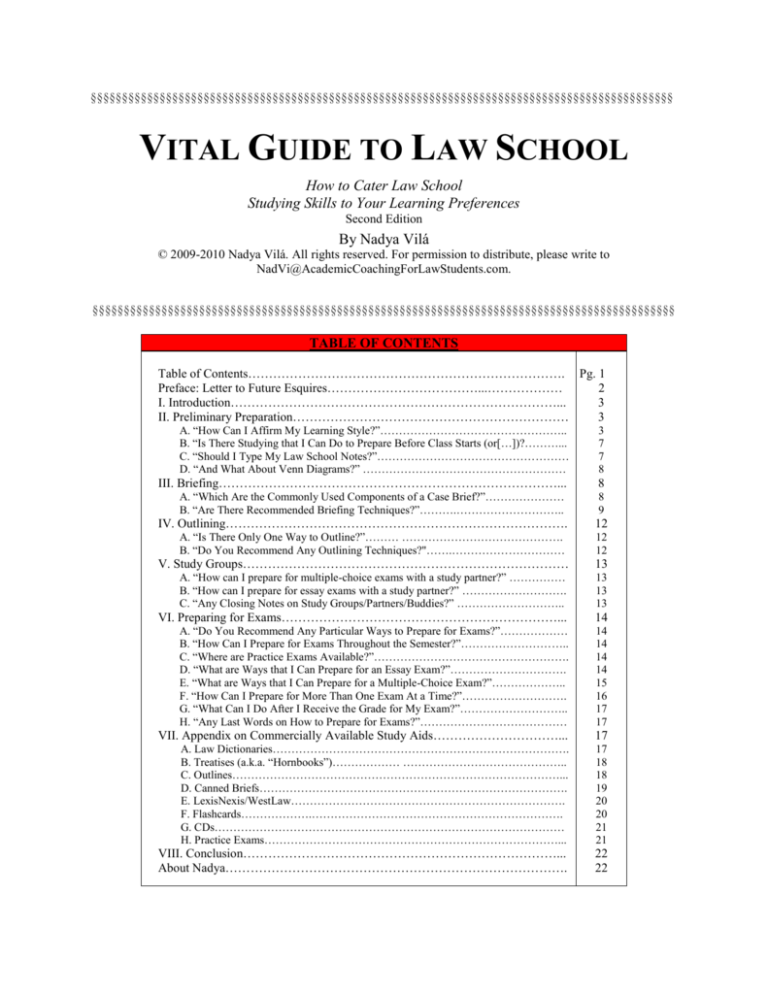

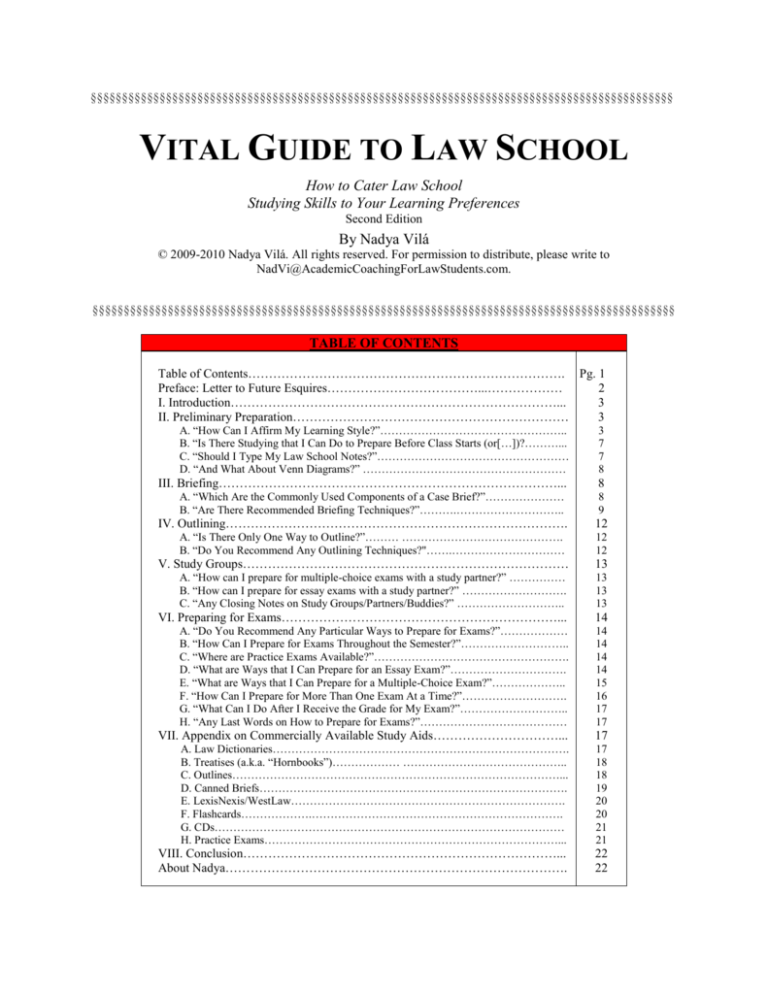

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………. Pg. 1

Preface: Letter to Future Esquires………………………………...………………

2

I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………...

3

II. Preliminary Preparation…………………………………………………………

3

A. “How Can I Affirm My Learning Style?”…………………………………………..

B. “Is There Studying that I Can Do to Prepare Before Class Starts (or[…])?………...

C. “Should I Type My Law School Notes?”……………………………………………

D. “And What About Venn Diagrams?” ………………………………………………

3

7

7

8

III. Briefing………………………………………………………………………...

8

A. “Which Are the Commonly Used Components of a Case Brief?”…………………

B. “Are There Recommended Briefing Techniques?”……….………………………..

8

9

IV. Outlining……………………………………………………………………….

12

A. “Is There Only One Way to Outline?”……… …………………………………….

B. “Do You Recommend Any Outlining Techniques?"…….…………………………

12

12

V. Study Groups……………………………………………………………………

13

A. “How can I prepare for multiple-choice exams with a study partner?” ……………

B. “How can I prepare for essay exams with a study partner?” ……………………….

C. “Any Closing Notes on Study Groups/Partners/Buddies?” ………………………..

13

13

13

VI. Preparing for Exams…………………………………………………………...

14

A. “Do You Recommend Any Particular Ways to Prepare for Exams?”………………

B. “How Can I Prepare for Exams Throughout the Semester?”………………………..

C. “Where are Practice Exams Available?”…………………………………………….

D. “What are Ways that I Can Prepare for an Essay Exam?”………………………….

E. “What are Ways that I Can Prepare for a Multiple-Choice Exam?”………………..

F. “How Can I Prepare for More Than One Exam At a Time?”……………………….

G. “What Can I Do After I Receive the Grade for My Exam?”………………………..

H. “Any Last Words on How to Prepare for Exams?”…………………………………

14

14

14

14

15

16

17

17

VII. Appendix on Commercially Available Study Aids…………………………...

17

A. Law Dictionaries…………………………………………………………………….

B. Treatises (a.k.a. “Hornbooks”)……………… ……………………………………..

C. Outlines……………………………………………………………………………...

D. Canned Briefs……………………………………………………………………….

E. LexisNexis/WestLaw……………………………………………………………….

F. Flashcards……………….………………………………………………………….

G. CDs…………………………………………………………………………………

H. Practice Exams……………………………………………………………………...

17

18

18

19

20

20

21

21

VIII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...

About Nadya……………………………………………………………………….

22

22

PREFACE: LETTER TO FUTURE ESQUIRES

Dear law students and other friends:

On the day I was buying attorney malpractice insurance, my body froze as I researched insurance

plans. Something felt odd; I took a deep breath and realized I missed working with students.

Seconds later, I called the Council on Legal Education Opportunity (CLEO - found at

www.cleoscholars.org). I asked if I could help with any of its upcoming academic workshops for

law students. The conference coordinator stated he had just realized he needed someone to teach

a workshop on a topic I love: personalizing law school study skills.

In short, I accepted the opportunity to present at the workshop (I jumped at it, really), and

gathered my materials for the presentation. In result, the first edition of this guide was born. I had

a blast presenting it at the conference. The related student feedback was wonderful, too.

Since then, I have worked with academic success professors and colleagues to polish the guide’s

contents. I also worked with law students and incorporated their suggestions and feedback into

this second edition. Overall, I am fortunate and infinitely grateful for the support I have received

in developing this guide.

Thank you to you as well for including the Vital Guide to Law School in your preparation for

law school success! I have had a wonderful time putting its materials together, and it is a

pleasure to share its contents with you now. Along your law school journey, you are welcome to

keep me posted. I encourage your questions and feedback and can be reached at

NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com.

Yours sincerely,

Nadya Vilá

December 2010

2

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

VITAL GUIDE TO LAW SCHOOL

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. For permission to distribute, please write to NadyaVila@gmail.com.

I. INTRODUCTION

Law school is about finding blackletter law, learning it, and applying it to an exam or

memorandum of law. Outside of that, the purpose of the cases is to teach you facts that will

trigger when to use the law applied. The Socratic method is used to get students accustomed to

thinking on their feet. Finally, exams serve the purpose of giving students a grade so that they

can graduate.

The basic study regime in law school includes the following:

Preliminary preparation

Briefing/finding the blackletter law

Outlining/organizing subject notes

Preparing for exams

Study groups

Each of these elements is discussed in detail below. You will also find an appendix detailing the

differences between various commercial study aids. But first, I would like to offer one definition;

Black’s Law Dictionary (discussed on pages 17-18) defines “blackletter law” as “[o]ne or more

legal principles that are old, fundamental, and well settled.”1

II. PRELIMINARY PREPARATION

This category can be called the “know yourself” category. It includes things you can do to

discover your learning preferences (or reaffirm them) prior to starting law school. The category

also includes ways to prepare for class before law school starts or before a new unit of material is

started within a class.

A. “How Can I Affirm My Learning Style or Preference?”

My personal experience has been that taking the Meyers Briggs Type Indicator exam is

invaluable when it comes to defining your learning preferences! I find that this test (a word used

loosely) is highly useful because it goes beyond “audio learner, visual learner, or tactile learner”

classifications and covers other ways that people process ideas. You may want to consider

reading about the test at http://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/. I will provide

some more information below, but first, the following:

1

“Blackletter law.” Black’s Law Dictionary. Second Pocket Edition. 2001.

3

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

NADYA’S NOTE #1: Disclaimer about the MBTI®

Please read prior to proceeding.

I am NOT a licensed MBTI exam administrator; I am simply a fan. Personally, I found my MBTI

score to be useful throughout law school. I am discussing it here in case you find your own score

useful, too. The test is often given at university career centers and counseling centers; your law

school may offer it as well. You may want to consider contacting your law school to ask if the

exam is available.

Most of the information in this section is borrowed from the following webpage: www.capt.org.

1. Taking the MBTI® Online

The MBTI exam is administered online by multiple organizations. MBTI®Complete, available

at www.mbticomplete.com and by calling (800) 624-1765, offers an online version of the exam

for only $59.95. The Center for Applications of Psychological Type (CAPT) offers the exam

along with a telephone follow-up consultation for $150. More information on CAPT is available

below. CAPT can be found at www.capt.org (interesting note; a CAPT employee told me about

MBTIComplete). Finally, Facebook may have an MBTI application, although I cannot attest to

its accuracy or thoroughness.

2. About the MBTI® Instrument

The MBTI® (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®) instrument measures personality preferences on

four different scales: Extraversion (E) – Introversion (I), Sensing (S) – Intuition (N), Thinking

(T) – Feeling (F), and Judging (J) – Perceiving (P). Results from the indicator are delivered in a

four letter type (i.e. ENFJ).

The MBTI instrument contains four separate indices. Each index reflects one of four basic

preferences which, under [C. G. Jung’s (1921/1971)] theory, direct the use of perception and

judgment. The preferences affect not only what people attend to in any given situation, but also

how they draw conclusions about what they perceive.

a. The Extraversion–Introversion (E–I) Index

This index affects choices as to whether to direct perception judgment mainly on the outer world

(E) or mainly on the inner world of ideas. Overall, the E–I index is designed to reflect whether a

person is an extravert or an introvert in the sense intended by Jung….Extraverts are oriented

primarily toward the outer world; thus they tend to focus their perception and judgment on

people and objects. Introverts are oriented primarily toward the inner world; thus they tend to

focus their perception and judgment upon concepts and ideas.

4

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

NADYA’S NOTE #2 (Based on What Was Discussed at Her Law School Orientation and

Expert Learning for Law Students by Prof. Michael Schwartz)2

When applied to law school, an “E” index score indicates that a person learns more easily through

extroverted matters, such as discussion, where as a person with an “I” score may prefer internal

consideration and reflection when learning material.3

b. The Sensing–Intuition (S–N) Index

Generally, the S-N index affects choices as to which kind of perception is preferred when one

needs or wishes to perceive. It is designed to reflect a person's preference between two opposite

ways of perceiving; one may rely primarily upon the process of sensing (S), which reports

observable facts or happenings through one or more of the five senses; or one may rely upon the

less obvious process of intuition (N), which reports meanings, relationships and/or possibilities

that have been worked out beyond the reach of the conscious mind.

NADYA’S NOTE #3 (Based on What Was Discussed at Her Law School Orientation and

Expert Learning for Law Students by Prof. Michael Schwartz)

When applied to law school, individuals scoring in the “N” index may feel more comfortable with cases

(and thus read them more quickly) if they know the rule of law involved prior to reading the case.4 Part

Two of the Guide (starting on page 17) provides sources that offer rule of law context.

c. The Thinking–Feeling (T–F) Index

Overall, the T-F index affects Choices as to which kind of judgment to trust when one needs or

wishes to make a decision. The T–F index is designed to reflect a person's preference between

two contrasting ways of judgment. A person may rely primarily through thinking (T) to decide

impersonally on the basis of logical consequences, or a person may rely primarily on feelings (F)

to decide primarily on the basis of personal or social values.

NADYA’S NOTE #4 (Based on What Was Discussed at Her Law School Orientation and

Expert Learning for Law Students by Prof. Michael Schwartz)

You can do very well in law school regardless of what you score in the T-F index. You can do very well

in law school regardless of what you score in any index.5

2

See Michael Hunter Schwartz, Expert Learning for Law Students (2d ed. 2008).

See Michael Hunter Schwartz, Expert Learning for Law Students (2d ed. 2008).

4

See Michael Hunter Schwartz, Expert Learning for Law Students (2d ed. 2008).

5

See Michael Hunter Schwartz, Expert Learning for Law Students (2d ed. 2008).

5

3

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

d. The Judgment–Perception (J–P) Index

Generally, the J-P index affects choices as to whether to deal with the outer world in the judging

(J) attitude (using T or F) or in the perceptive (P) attitude (using S or N). The index is designed

to describe the process a person uses primarily in dealing with the outer world, that is, with the

extraverted part of life.

A person who prefers judgment (J) has reported a preference for using a judgment process (either

thinking or feeling) for dealing with the outer world. A person who prefers perception (P) has

reported a preference for using a perceptive process (either S or N) for dealing with the outer

world.

NADYA’S NOTE #5 (Based on What Was Discussed at Her Law School Orientation and

Expert Learning for Law Students by Prof. Michael Schwartz)

When applied to law school, individuals scoring a “J” may feel more comfortable learning when using

strict(er) organization methods for their notes and materials than those who score a “P”.6

3. Identifying the MBTI Preferences

The main objective of the MBTI instrument is to identify four basic preferences. The indices E–p

I, S–N, T–F, and J–P are designed to point in one direction or the other. They are not designed as

scales for measurement of traits or behaviors. The intent is to reflect a habitual choice between

rival alternatives, analogous to right handedness or left-handedness. One expects to use both the

right and left hands, even though one reaches first with the hand one prefers. Similarly, every

person is assumed to use both poles of each of the four preferences, but to respond first or most

often with the preferred functions or attitudes.

The 16 Types

As located on the Type Table

6

ISTJ

ISFJ

INFJ

INTJ

ISTP

ISFP

INFP

INTP

ESTP

ESFP

ENFP

ENTP

ESTJ

ESFJ

ENFJ

ENTJ

See Michael Hunter Schwartz, Expert Learning for Law Students (2d ed. 2008).

6

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

B. “Is There Studying that I Can Do to Prepare Before Class Starts (or Before a New Unit

is Started Within a Class)?”

Absolutely! The techniques discussed here may be particularly useful for intuitive learners since

they tend to enjoy caselaw more when they know the rule of law involved in a case prior to

reading the case. However, even if you are not an intuitive learner, you may want to consider

getting an overall grasp on a class topic, or at least the first subtopic within a class, during the

vacation break before the semester starts. For example, you can listen to a CD outline for your

Criminal Procedure class, or you can read the blackletter law for the intentional torts unit

discussed in your Torts class, before your first day of the semester.

1. Preparatory Work for Audiovisual Learners

My favorite technique for audiovisual learners includes listening to course CDs and typing notes

(or handwriting notes). Essentially, this gives individuals the chance to type a course outline and

become familiar with it prior to taking the course. For a breakdown of several commercial brand

law school course CDs and how they vary, please see page 21.

2. Preparatory Work for Auditory Learners

An auditory learner may feel perfectly comfortable listening to CDs only. However, in the long

run, he or she may get the most out of the time spent listening to CDs by taking notes on the

lectures.

3. Preparatory Work for Visual Learners

A visual learner may choose to read a skeleton outline (blackletter law only) provided by a

student who has already taken the course or provided by a commercial source (for a list of

commercial outline sources, please see pages 18-19). However, the student may also benefit

from listening to CDs and typing/writing notes.

C. “Should I Type My Law School Notes?”

Personally, I recommend typing notes throughout law school. Ultimately, it becomes easier to

keep notes organized per class, and outlining subject matters becomes a relative breeze. For

individuals who prefer handwriting, there will be opportunities to learn via handwriting in the

study plans discussed here even if you do type your briefs and class notes. When it comes to

briefing and class, it is best to process the law and record what you learn as quickly as possible,

essentially because law school tends to fly by. Typing notes can ultimately be a great way to save

time.

If you prefer to have handwritten notes in class, or if you are not permitted to use a computer in

class, a handwritten note-taking format for law school briefing is discussed on pages 11-12.

7

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

Additionally, this is a good time to introduce Venn Diagrams, which are often hand-written and

can be used at different stages of the law school study process.

D. “And What About Venn Diagrams?”

Venn diagrams7 can be wonderful tools for visual learners, and they can be useful to tactile and

auditory learners as well. Traditionally, they tend to consist of circular diagrams. (Please see

Figure A, below). More loosely, Venn diagrams can also be made of straight lines (Figure B,

below), or a combination of the two. They are usually hand-written, and they can be an excellent

way to summarize a paragraph or topic in the margin of your casebook, outline, etc. The text of

the diagrams themselves can be used to clarify definitions. It can also be used to draft the flow of

a topic, such as how a stop in Criminal Law can evolve into a lawful arrest.

Figure A

Torts Definitions

Figure B

Torts Definition

of Trespass to Land

III. BRIEFING

A. “Which Are the Commonly Used Components of a Case Brief?”

Case briefing boils down to dissecting case law for certain components, which typically include

the following (your professor may require different components):

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

the case’s procedural history,

the case’s legal issue(s),

facts supporting the case,

rule of law found in the case,

the court’s holding, and

the court’s reasoning, policy, etc.

7

Wikepedia, the Free Encyclopedia;Venn diagrams, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venn_diagram (Also

called “set diagrams,” Venn diagrams are “diagrams that show all hypothetically possible logical relations between a

finite collection of sets (aggregation of things).” “Venn diagrams were conceived around 1880 by John Venn.”).

8

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

B. “Are There Recommended Briefing Techniques?”

1. Rainbow Highlighting

Personally, I enjoyed using rainbow highlighting, which consists of assigning a highlighter color

to each briefing component (i.e. purple for procedural history, pink for legal issues, etc.).

I would highlight items in the book accordingly and then type notes. When presenting in class, I

found that having color coded notes allowed me to find information faster.

As for which highlighters I used (my mind was once preoccupied with this in law school), I

actually preferred erasable color pencils by Crayola (I never came across ones made by another

brand). Highlighting tends to be unforgiving unless it is erasable, and even then it fades with

time and can make books look unattractive and stained. For me, erasable color pencils avoided

those issues nicely.

2. Organization of Case Briefs

As for keeping my briefs organized, I preferred to organize them along the lines of my

casebook’s table of contents to the extent that the professor was following it. It made the

transition to outlining a breeze. In short, you may want to consider typing up your table of

contents and inserting your briefs accordingly. Then, as you begin to outline your material, you

can condense your notes within the pre-set outline format. Similarly, products such as RomLaw

sell software that includes tables of content for many popular casebooks. However, typing the

table of contents yourself can be a great way to get an overview of the unit, quickly.

Regardless of how you choose to organize your briefs, you may want to consider abbreviating

words (i.e. the letter “R” for “reasonable” and “Q” for question) and citing page numbers to save

time. For example, in the example of a brief below, numbers found after “CB” indicate where the

case is found in the casebook. While it is not imperative to note the case citation, providing the

year the case was decided is important.

Additionally, if you incorporate information from another study source (such as a commercial

outline), you may want to indicate where you found the material. This will save you time if you

work in study groups or swap notes with a classmate; you will be less likely to find yourself

sifting through stacks of papers to verify a point you found weeks earlier.

Please See Next Page for

“Nadya’s Note #6: Example of an

Internet Law Case Brief”

9

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

NADYA’S NOTE #6: Example of an Internet Law Case Brief

A. Privacy of Communications

1. Privacy and New Technology

A. Olmstead v. United States, 7 U.S. 438, (1928), CB 491

Pro His: District Court for the Western District of Washington convicted Ds.

Issue: Whether the use of evidence of private telephone conversations b/w the Ds

and others, intercepted by means of wire tapping, amounted to a violation of the

Fourth and Fifth Amendments.

Facts: Ds were convicted of conspiring to violate the National Prohibition Act (27

USCA). Info which led to the discovery of the conspiracy and its nature was obtained by

wire tapping (small wires were inserted along the ordinary telephone wires from the

residences of four of the petitioners and those leading from the chief office). The

insertions were made in the basement of a large office building.

Rule: The R view is that one who installs in his house a telephone instrument with

connecting wires intends to protect his voice to those quite outside, and that the

wires beyond his house, and messages while passing over them, are not within the

protection of the Fourth Amendment.

2. This case establishes the Olmstead Test:

1) In order to constitute a search, the searchers had to physically trespass

onto the land.

Holding: Post office provides privacy because of the constitutional provision of

the Post Office Dep and the relations between the gov and those who pay to

secure protection of their sealed letters. Meanwhile, establishing a R expectation

of privacy for phone conversations should be created by legislation, not by

expanding the Fourth.

Dissent: The Constitutional Amendments can be construed and the Fourth and

Fifth should be expanded to include rights of privacy for telephone conversations.

There is no difference between the sealed letter and the private telephone

message. THE GREATEST DANGERS TO LIBERTY LURK IN INSIDIOUS

ENCROACHMENT BY MEN OF ZEAL, WELL MEANING BUT WITHOUT

UNDERSTANDING. (J Breindeis)

Class Notes: Katz overturned this holding by providing that the tapping of a

public telephone was a search and seizure subject to the Fourth Amendment.

Generally, privacy is observed where

1) the person has exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy

2) the expectation be one that society is prepared to recognize as “reasonable.”

3. “What If I Prefer to (Or Am Required to) Handwrite My Case Briefs?”

In law school, some professors do not allow students to use computers in class. Some students

simply prefer to hand-write their notes. Consequently, the traditional Cornell Note-Taking,

evidenced in Figure A, below, can be adapted to law school and used for hand-writing notes, as

per Figure B.

10

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

Figure A

Figure B

Traditional Cornell Note-Taking

Law School-Friendly “Cornell-ish” Note-Taking

Questions

1. Which Constitutional Amendment

addresses the Establishment Clause?

Answers

First

Amend.

2. Why did the chicken cross the

road?

Get to

other

side.

Summary:

1. Establishment = First

2. Chicken = Other Side

Briefs

A. Privacy of Communications

1. Privacy and New Technology

A. Olmstead v. United States, 7 U.S. 438,

(1928), CB 491

Pro His: District Court for the Western District of

Washington convicted Ds.

Issue: Whether the use of evidence of private

telephone conversations b/w the Ds and others,

intercepted by means of wire tapping, amounted to a

violation of the Fourth and Fifth Amendments.

Facts: Ds were convicted of conspiring to violate the

National Prohibition Act (27 USCA). Info which led

to the discovery of the conspiracy and its nature was

obtained by wire tapping (small wires were inserted

along the ordinary telephone wires from the residences

of four of the petitioners and those leading from the

chief office). The insertions were made in the

basement of a large office building.

Rule: The R view is that one who installs in his house

a telephone instrument with

connecting wires

intends to protect his voice to those quite outside, and

that the wires beyond his house, and messages while

passing over them, are not within the protection of the

Fourth Amendment.

2. This case establishes the Olmstead Test:

1) In order to constitute a search, the searchers had to

physically trespass

onto the land.

Holding: Post office provides privacy because of the

constitutional provision of the Post Office Dep and the

relations between the gov and those who pay to secure

protection of their sealed letters. Meanwhile,

establishing a R expectation of privacy for phone

conversations should be created by legislation, not by

expanding the Fourth.

Dissent: The Constitutional Amendments can be

construed and the Fourth and Fifth should be expanded

to include rights of privacy for telephone

conversations. There is no difference between the

sealed letter and the private telephone message. THE

GREATEST DANGERS TO LIBERTY LURK IN

INSIDIOUS ENCROACHMENT BY MEN OF

ZEAL, WELL MEANING BUT WITHOUT

UNDERSTANDING. (J Breindeis)

Class

Notes

*Katz

overturned this

holding by

providing that

the tapping of a

public

telephone was a

search and

seizure subject

to the Fourth

Amendment.

Unit/Course/Class Summary:

Unit = Generally, privacy is observed where:

1) the person has exhibited an actual (subjective)

expectation of privacy

2) the expectation be one that society is prepared to

recognize as “reasonable.”

a. Traditional Cornell Note-Taking

Specifically, in traditional Cornell Note-Taking, the student divides the paper into two columns:

the note-taking column (usually on the right) is twice the size of the key word column (on the

left). The student should leave five to seven lines, or about two inches (5 cm), at the bottom of

the page.”8 “After the notes have been taken, the student writes a brief summary in the bottom

five to seven lines of the page.”9

8

Wikepedia, the Free Encyclopedia; Cornell Notes, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornell_Notes (“Notes

from a lecture or teaching are written in the note-taking column; notes usually consist of the main ideas of the text or

11

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

b. Law School “Cornell-Ish” Note-Taking

Alternatively, for law school note-taking, briefing can be done in the left ¾ of the page. Class

notes are jotted in the right column. The student can choose to summarize the unit, course, and/or

class in the summary box at the bottom of the page. As with traditional Cornell Note-Taking,

“the student is encouraged to reflect on the material and review the notes regularly.”10

IV. OUTLINING

A. “Is There Only One Way to Outline?”

Thankfully, the answer to that question is “no.” Outlines are both study tools that a student can

create throughout a class as well as commercial products that are readily available. In this

section, I will highlight self-created outlines (commercial outlines are discussed on pages 18-19).

Ultimately, self-created outlines are meant to be a tool for learning; no one will grade them (most

probably), and they do not have to be perfectly styled. You do not even have to write them

(again, most probably).

The process of compiling an outline and trimming it can, however, be useful. Often, the loose

pieces of law merge into a larger picture during the outlining process. Also, having an outline

will give you a quick reference point for exams, future classes, and even work. Most importantly,

outlining can be the perfect opportunity to synthesize the rule of law within cases or units.

B. “Do You Recommend Any Outlining Techniques?”

Similar to writing briefs, when it comes to drafting your own outlines, you may want to consider

abbreviating words and citing page numbers to save time. If you incorporate information from

another study source (such as a commercial outline), you may want to indicate where you found

the material. For example, materials from an Emanuel’s outline can be highlighted in blue.

Below you will find an example of the case brief used above as it appears in the chapter outline.

Since the case had already been discussed in class, I trimmed several of the elements and

provided the rule, which the professor provided was the testable component.

Please See Next Page for

“Nadya’s Note #7: Excerpt from

an Internet Law Student Outline”

lecture, and long ideas are paraphrased. Long sentences are avoided; symbols or abbreviations are used instead. To

assist with future reviews, relevant questions[,] which should be recorded as soon as possible so that the lecture and

questions will be fresh in the student's mind[,] or key words are written in the key word column.).

9

Id. (This helps to increase understanding of the topic. When studying for either a test or quiz, the student has a

concise but detailed and relevant record of previous classes.

“When reviewing the material, the student can cover up the note-taking (right) column to answer the

questions/keywords in the key word or cue (left) column....”).

10

Wikepedia, the Free Encyclopedia; Cornell Notes, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornell_Notes.

12

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

NADYA’S NOTE #7: Excerpt from an Internet Law Student Outline

A. Privacy of Communications

Rule Synthesis: Generally, privacy is observed under the Fourth Amendment

Where the following exists:

1) the person has exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy

2) the expectation be one that society is prepared to recognize as “reasonable.”

1. Privacy and New Technology

A. Olmstead v. United States, 7 U.S. 438, (1928), CB 491 CONTRASTS WITH

SEALED MAILED LETTERS

Rule: Olmstead Test: 1) In order to constitute a search, the searchers had to

physically trespass onto the land.

Notes: “This is an important case because it is one of the first ones where the

issue involves technology and the fourth amendment.

2. Katz overturned this holding by providing that the tapping of a public telephone was a

search and seizure subject to the Fourth Amendment.

V. STUDY GROUPS

Study groups can provide motivation and can be used to verify rules of law, as well as clarify the

application of law. Overall, studying together is wonderful as long as it is productive. Some

individuals choose to “do their own thing” while sitting in a group, and they consider the

company around them to be their study group. In contrast, I had study buddies for certain classes.

We mostly took turns clarifying law for each other. We also swapped notes and used each

other’s work to flesh out our own when creating outlines, and I found that to be very useful.

However, we mostly studied independently.

A. “How can I prepare for multiple-choice exams with a study partner?”

If you happen to be preparing for a multiple-choice exam, I feel that you may want to consider

answering some multiple-choice practice questions with a classmate. You can take turns reading

the questions and discussing the answers. This technique may be particularly useful for

extroverted students who learn well through discussion. Generally, I found that I remembered the

sneaky tricks of law faster when I learned them via discussion. I did not always answer questions

with a study buddy, but I am glad that I did on occasion. Similarly, flash cards (discussed on

pages 20-21) can be reviewed with a study buddy.

B. “How can I prepare for essay exams with a study partner?”

When it comes to essay exams, you may want to swap practice answers with a study buddy.

While doing so is a useful tool, I also recommend having your Professor or Professor’s Assistant

review at least one of your practice answers, particularly during your first year of law school.

13

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

Having her or him review your work will most likely give you inside information on how the

professor grades before your performance counts for a grade.

C. “Any Closing Notes on Study Groups/Partners/Buddies?”

Study buddies and groups tend to be most effective when members share equal responsibilities

and contribute or participate equally. I was once told that the most important thing about study

groups is that a person should be able to leave – no hard feelings – if the dynamic is not

productive for her or him. I feel it is appropriate to share that principle here.

Additionally, even if you choose to study alone, you may want to consider being the first to offer

a helping hand to a classmate in need.

VI. PREPARING FOR EXAMS

A. “Do You Recommend Any Particular Ways to Prepare for Exams?”

Yes! Overall, you may want to consider preparing for exams using practice exams. The

techniques you employ while preparing may vary based on whether you will be taking an essay

exam or a multiple-choice exam. In this section, I will offer tips for both types of exams. I will

also discuss preparing for more than one exam at once. In Part Two of the Guide (starting on

page 17), I will discuss where to get practice exams that you can use whether you study alone,

with a study buddy, or in a group.

B. “How Can I Prepare for Exams Throughout the Semester?”

You may choose to occasionally quiz yourself on topics of law by answering multiple-choice

questions related to the subtopic at hand. You can review essay exams, too. Moreover, if the

Professor or a class assistant holds a review session, do everything within reason to attend.

Assistants often use those opportunities to disclose information - or even particular questions –

given on exams. Professors may even share their exam topics at their final reviews.

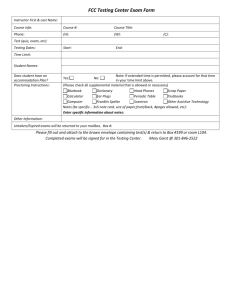

C. “Where are Practice Exams Available?”

Practice exams can be obtained from professors and from an Academic Success program. Some

law schools post them online, too. Sometimes, it can be appropriate to use bar review materials

to prepare for a law school exam. There are also commercial sources specifically dedicated to

law school exams. These sources are discussed on pages 21-22.

D. “What Are Ways that I Can Prepare for an Essay Exam?”

First and foremost, during the semester, you may want to consider taking a practice exam and

having your professor (or other final exam-grader) review it, if possible. This will probably

provide valuable information on how the professor thinks and grades.

14

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

1. “What about That One-Pager?”

During the preparation period before the exam, you are welcome to condense your course outline

into a short “memory jogger” or mnemonic that you can write within an average of seven

minutes. This is referred to as the “one-pager,” although the final result may be as short as a

sentence or as long as a few pages.

a. “What Are Ways That I Can Create and Memorize a One-Pager?”

As for writing and memorizing your one-pager, the Law in a Flash flashcard series instruction

booklet can be useful for building a mnemonic. Each box set’s instruction booklet includes a

mnemonic for the topic discussed in the flashcard set. I find that the mnemonics tend to be a

good starting point for writing a condensed outline. The instruction booklet also provides

information on the 10-1-10-1 method, which is described below in Nadya’s Note #8. The Law in

a Flash flashcard series is discussed further on pages 20-21.

NADYA’S NOTE #8: On the 10-1-10-1 Approach for Memorizing

“…In fact, you should be able to memorize any mnemonic you need in a one-day period, if you follow

this program, commonly called the “10-1-10-1” approach. Look at any mnemonic you need to memorize

(including the general course mnemonic), put it aside, and immediately write it down. Repeat this until

you have it down perfectly. Then, write it down after ten minutes. Fill in any gaps. Wait one hour,

and write it down again. Do the same in ten hours, and then after one day. That’s it - 10 minutes, 1

hour, 10 hours, 1 day. Why approach it this way? Because these are the intervals at which, memory

experts believe, memory breaks down. You should do this program as close to your exam as possible; if

there will be a significant gap before your exam, reinforce your memory by copying the mnemonic down

as frequently as you find necessary. Remember - you have to be able to remember these elements

flawlessly.”11

b. “How Can I Apply the One-Pager?”

On the day of the exam, strut into the testing site. Once your exam is issued to you, and before

you look at it, write your one-pager on a scratch sheet of paper. After you are finished, proceed

to read the call of the question first. Outline an answer based on the material in your one-pager.

Proceed to have fun. If you are hours into the exam and cannot remember a point or detail of

law, don’t worry; you have your one-pager.

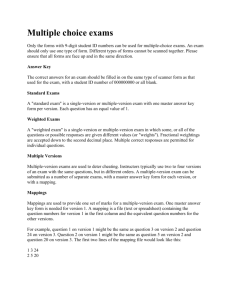

E. “What Are Ways that I Can Prepare for a Multiple-Choice Exam?”

You may want to consider asking your Professor or the Professor’s Assistant if the class exam’s

questions are similar to any particular brand of commercially available questions. Once you

Excerpt cited from a “Law in a Flash” flashcards instruction booklet, © Copyright 2002 Aspen Law & Business.

Emphasis added.

15

11

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

know how many multiple-choice questions to expect, do as many multiple-choice questions as

time reasonably allows. Information on the differences between certain commercial brands of

practice multiple-choice questions is available on pages 21-22.

1. “Are There Techniques I Can Apply to Answering Multiple-Choice Questions?”

One of most effective professors recommended these “Zen Test-Taking” strategies discussed

below when answering multiple-choice questions. This “philosophy” discussed below is not

related in any way to any existing testing programs (that I am aware of). It provides that

multiple-choice tests basically test speed reading and comprehension. The questions are

essentially about issue spotting. In law school, the questions typically test on one of the rule’s

elements. The professor went on to recommend the information in Nadya’s Note #9, of which

my favorite point is “read the call of the question first!”

NADYA’S NOTE #9: ON ZEN TEST-TAKING AND MULTIPLE-CHOICE EXAMS

The goal is to read the question once if you want to finish the exam.

Read the call of the question first

Read facts in a deliberate or quick matter

o Take notes. You can also draw pictures (particularly with property questions)

Examine answers.

Each answer choice is an independent answer not relevant to the other.

o Check if each answer choice is true or false.

The best answer will have law-fact analysis.

The second best answer will have statement of law.

The third best answer will have statement of fact.

o The answer must have the correct explanation, such as “if this event occurs, then that is the

answer.”

When given tear questions (i.e. “How many, if any, of the following points are/is true), answer each

individual option as a True/False question. Then tally the results and choose the multiple-choice answer

that best reflects your tally.

If you go back to a question, act like you have never seen it before and go over all of the answers.

o If you have an epiphany, choose the new answer.

o If you do not have an epiphany, leave the first answer.

F. “How Can I Prepare for More Than One Exam At a Time?”

In actuality, you may want to consider preparing for one exam at a time, even if you have several

exams scheduled for one day. For example, if you have two exams on the same day, you can

memorize your one-pager for your first exam. After you memorize the one-pager for exam A,

begin on your one-pager for exam B. As you prepare for exam B, review your one-pager for

exam A on occasion; rewrite it if necessary until it is error-free.

If you have to prepare for a multiple-choice exam while you prepare for an essay exam, you can

choose to answer a certain amount of multiple-choice questions. Then, during the time in which

you would review one of your one-pagers, you can review brief notes from the multiple-choice

16

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

questions. Of course, you can also prepare the one-pager first and then answer the multiplechoice questions.

G. “What Can I Do After I Receive the Grade for My Exam?”

Review your exam after your get your grade! Registrars make mistakes on occasion (rarely, very

rarely, but on occasion). More importantly, you may have the professor again in your law school

career. By reviewing your exam and learning how she or he grades, you may perform better on

the professor’s next exam. At the least, you will probably have an easier time preparing.

Ultimately, though, exams are part of the learning process. In order to truly learn the material, it

is often best to understand how you performed on the exam based on the test-giver’s perspective.

Your self assessment of strengths, weaknesses, and skills on exams will be valuable, too

(meanwhile, you are encouraged to list those strengths, weaknesses, and skills accordingly).

H. “Any Last Words on How to Prepare for Exams?”

Just a few:

1. If you have an open-note exam, bind your notes and include a table of contents or use

tabs in order to make material easy to find.

2. Write legibly. Very legibly.

3. If you have to stop writing for any reason, stop mid sentence. Doing so will make it

easier to get back into the “flow” of what you are writing when you return. You can read

the unfinished sentence and continue writing (rather than rereading everything you wrote

to recall your flow). Thank you, Wendy Bishop’s The Subject is Writing (Boynton/Cook

Publishers, Inc. 1999), for this information.

4. If working on a take-home exam (or a memorandum of law), resist the urge to edit as you

type. Instead, write a rough first draft and then review your work.

5. When writing an essay answer, use headings and underline important elements in order to

make your essay easy to digest.

6. You may want to consider using a digital watch to time yourself if the exam proctor

allows. At the least (or most), you can have a digital watch and one with a second-hand

on it.

VII. APPENDIX ON COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE STUDY AIDS

The following is a list of certain types of popular study aids: dictionaries, treatises, outlines,

canned briefs, flashcards, CDs, and practice exams. The purpose of each type of aid is discussed

below along with information on some available brands.

A. Law Dictionaries

Several brands of law dictionaries are available. However, Black’s Law Dictionary has the

reputation for being “the best” brand of dictionaries. Black’s tends to be available in a pocket

version, a full-length version, and a deluxe full-length version. There is also a phone application.

17

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

The pocket version of Black’s Law Dictionary is useful. However, most of my classmates and I

found that the pocket version could only guide us through the first four to six weeks of class.

After that, we needed material only found in the full-length dictionaries. Thus, in my opinion,

owning a pocket version can be useful but is not necessary.

As for the full-length versions, the main differences between the regular full-length and the

deluxe versions are that the deluxe offers leather binding and tabbed divisions. You are welcome

to invest in a regular full-length version and inserting tabs at the beginning of each letter’s

section in order to save money and have a product similar in appearance to the deluxe version.

Black’s Law Dictionary is also available through WestLaw and possibly LexisNexis (both

discussed below). However, I found searching on the WestLaw version to be cumbersome (and

students do not necessarily have WestLaw or LexisNexis access at the beginning of their first

year, thus making the availability of the resource unreliable).

B. Treatises (a.k.a. “Hornbooks”)

Treatises are similar to casebooks (the books where you find the cases for your class) in style and

presentation. However, whereas casebooks hide blackletter law in cases, treatises highlight the

law first and then offer explanations for it. While useful, treatises can be more verbose than other

written study aids discussed below.

C. Outlines

Outlines are both study tools that a student can create throughout a class as well as commercial

products that are readily available. Often, the best way to use the commercial product is to

incorporate its information into your own outline. This can either be done by reading the notes

on the subject being discussed in class either prior to or after reading your cases. The student

may also choose to look up his case in the outline’s case index, read the outline material for the

case, and then brief the material. Intuitive learners will probably prefer reading the outline (or a

canned brief, discussed below) in some way prior to briefing a case.

Outlines are interesting in that they often include a key that links the material in your casebook

to where it can be found in the outline. Their information is often more succinct than that of

treatises. However, outlines do not always offer enough facts to flesh out the law, which is why

reading the case itself can be important.

1. “Which are Some of the More Popular Brands of Commercial Outlines?”

The following are some of the more popular brands of commercial outlines:

a. Emanuel® Law Outlines

Emanuel’s outlines are time trusted and have a reputation for being reliable. In my opinion,

sometimes their pages are content-heavy, which may lead to a lot of squinting. Ultimately,

choosing between an Emanuel Outline and a Gilbert Law Summary (discussed below) may

18

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

depend on price and on whether the person who authored the outline also authored your

casebook.

b. Gilbert Law Summaries

Gilbert’s outlines are also thorough and useful. To me, their pages are not as content-heavy,

which can make them easier on the eyes.

c. BarBri

BarBri is a company known for its bar review courses. Outside of that, if you choose to purchase

a BarBri plan during your first year (which I neither recommend nor oppose), BarBri will give

you a collection of outlines on first-year subjects. While the outlines are thorough, they do not

include many case citations, topic indexes, and case indexes. Thus, it can be difficult (or time

consuming, rather) to link the material in the outline to the material in your case. Additionally,

students may not receive the set of outlines until they are weeks into the semester. Finally, the

outlines have to be returned at the end of the year, which can be unfortunate.

On the other hand, if you happen to get the outlines, they can serve well during the exam prep

process when preparing for an exam that will not require the use of case names.

d. CrunchTime

CrunchTime outlines are published by the same company as Emanuel’s. They do not site as

many cases, if any, and they offer a cursory overview of the law. You may want to spend the

extra money on the complete Emanuel’s outline or a Gilbert’s outline. There often comes a point

in a class or a project when the student needs information not found in the CrunchTime outline,

and he or she ends up buying the larger outline, regardless. Getting the larger outline first may

save you money in the long run.

D. Canned Briefs

Canned briefs are collections of ready-to-go briefs keyed to certain popular casebooks. Because

most topics rely on specific cases, it is possible that the canned briefs for casebook A may have a

lot of the material needed for casebook B. Overall, it is not best to rely on canned briefs because

they may be inaccurate or only focus on a few of many important issues in a case. They can,

however, offer a useful quick background for a case, which can particularly come in handy for

intuitive learners.

There are several brands of canned briefs on the market. Personally, I am familiar with three of

them. I will list them in order from favorite to least favorite:

1) High Court ™ Case Summaries

When it comes to canned brief brands, this is the Cadillac of brands. Its material tends to be

accurate and creatively delivered. The entries even have pictures, which can help students recall

the case quickly (I was skeptical about this at first, but now I believe).

19

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

2) CaseNote™ Legal Briefs

Personally, I feel that CaseNote Legal Briefs should be chosen only when a High Court summary

is not available. I found the law in CaseNote briefs to be inaccurate and limited in more than one

occasion, and I would not want others to waste valuable time and money discovering the same.

3) Legalines™

Legalines offers a skeleton brief that can lack issues, important distinguishable facts, and

valuable notes on the court’s holding. I do not feel that Legalines products are useful for getting

the “A” (or rather, a thorough background on a case). Other people will tell you differently.

Personally, I feel that, rather than purchasing a Legalines, you may want to consider purchasing a

course outline and/or a High Court. You may also want to consider using your LexisNexis or

WestLaw plan as discussed below.

E. LexisNexis/WestLaw

LexisNexis and WestLaw are legal search engines that tend to offer complimentary plans for

students during their law school years. These plans allow students to research citations. Thus,

students can search the citation found in a casebook and find the case report online. In particular,

LexisNexis reports include a caption that provides the procedural history, an overview, and the

outcome of a case. They also provide headnotes, or important nuggets of law found within the

case, which can be useful for getting an overview of the case.

Similarly, while WestLaw reports do not provide an opening caption, they do offer headnote-like

citations that can offer an overview of the law involved.

One caveat with relying on LexisNexis or WestLaw as your sole study aid is that these services

report entire cases. The case reports shown in casebooks have often been edited to reflect a few

key points of law discussed in the case. A report in a casebook may be ten pages long, whereas it

might be seventy-five pages long online. Thus, by reading the material for every case online, you

may find yourself spending an excessive amount of time reading headnotes and briefing cases.

Another concern with relying solely on LexisNexis or WestLaw is that students may not receive

access to their accounts until they are weeks or months into their first semester.

F. Flashcards

Making your own flashcards can be a useful way to learn new law vocabulary. Meanwhile, there

are publishing companies that make commercial flashcards for law school. Of these, I am most

familiar with Law in a Flash.

20

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

Law in a Flash flashcards can be useful for their information, as well as for their instruction

booklets. Each topic’s instruction booklet includes a memory jogger – or mnemonic - that can be

useful for exams, particularly essay exams. Additionally, the booklets discuss the 10-1-10-1

method for memorizing, which can be helpful when memorizing memory joggers, definitions,

etc.

When it comes to buying all of the flashcards sets themselves, that is up to you. I do, however,

feel that the Evidence set is a must for the cards it offers on hearsay!!! I LOVE the examples the

cards give for the various rules of law; I feel that they were written clearly and more thoroughly

than what I found in outlines and my casebook.

G. CDs

CDs can be a fun way to get an overview of a course as well as learn during long trips. There are

several brands of CDs, of which I am familiar with three:

1. PMBR

PMBR CDs tend to offer direct, concise, blackletter law. However, I found the Contracts set to

be less direct when compared to other PMBR CDs, but still useful. Generally, these CDs are

available at law school bookstores, through PMBR, and as used products online. Some law

libraries have them as well.

As of recently, the PMBR bar review package offered to students in their third year included the

CDs for the six topics tested on the MBE. If you choose to buy the same PMBR CDs throughout

law school and do not want to receive a second set during your third year, you may be able to

negotiate with your PMBR representative for different study aids/

2. Sum & Substance

Sum & Substance CDs tend to be a tad longer and more elaborative than PMBR CDs, with the

Contracts set possibly being the exception. However, if you are interested in a more discussionfriendly lecture that offers a touch of history behind the law, then you may enjoy Sum &

Substance CDs.

3. Gilbert

I am only familiar with Gilbert CDs for topics that were not included in the PMBR or the Sum &

Substance CD collection. The CDs were useful, and they served their purpose during long trips

by giving me educational material to which I could listen.

H. Practice Exams

As mentioned earlier, practice exams can be obtained from professors and from an Academic

Success program. Sometimes, it can be appropriate to use bar review materials to prepare for a

21

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com

law school exam. Some law schools offer materials online. There are also commercial sources

specifically dedicated to law school exams.

1. Commercial Law School Exam Practice Exams

a.

PMBR Finals Series

Each publication within the PMBR Finals series includes a brief topical outline and multiplechoice questions. On occasion, they may offer essays as well (I recommend checking first).

There is one caveat with the multiple-choice questions; the answer explanations do not

always explain why the incorrect options are wrong. On the other hand, the multiple-choice

questions are somewhat bar exam-like in their complexity.

b. Q&A

The Q&A series is a LexisNexis publication that offers practice multiple-choice and short

answer questions. The questions are somewhat easier than PMBR Finals questions. However,

in the Q&A series, all answer options are explained, which can be wonderful; reading why

incorrect answers are wrong can be an excellent way to learn law.

VIII. CONCLUSION

Thank you for taking the time to review these materials. Please feel free to share your questions

and feedback; I can be reached at NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com.

ABOUT NADYA

Nadya Vilá has backgrounds in film production and fine arts, which she started to develop at the Dreyfoos

School of the Arts in West Palm Beach, Florida. At Florida State University, she continued to study film

and fine arts while earning a Bachelor's Degree in International Affairs. She sold her first photograph

while earning a Juris Doctor Degree in Law at Florida A&M University College of Law in Orlando,

Florida.

Nadya has practiced Intellectual Property law. Currently, she is Of Counsel to the Baez Law Firm, a

Criminal Defense firm, and is assisting clients with the incorporation of a charter school. She has worked

on cases regarding Employment Law and Construction Law.

Nadya is admitted to the bar of the State of Florida and the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Florida. She is a member of the American Bar Association and the Hispanic National Bar

Association. She enjoys advocating on behalf of alternative/democratic education programs, particularly

programs highlighting education in the fine arts.

Finally, Nadya is fluent in English and Spanish, and conversationally proficient in Italian. She is happily

learning French.

22

© 2009-2010 Nadya Vilá. All rights reserved. To distribute, please write to NadVi@AcademicCoachingForLawStudents.com