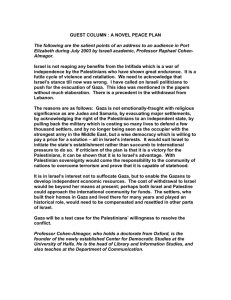

DOC

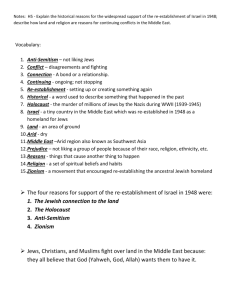

advertisement