Read the Paper

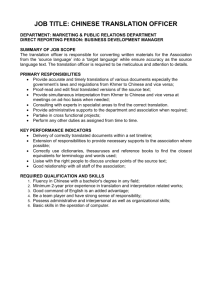

advertisement