Amy Hulsey - robertsap2010-2011

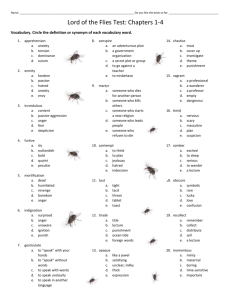

advertisement

Hulsey 1 Amy Hulsey Miss Roberts AP Literature 27 January 2008 Savagery and Sophistication: Reversion and Reentry As humans, we generally acknowledge that we are the most sophisticated, intelligent animal on the earth, and this is why we are the dominant species. However, it takes only a small amount of time and a small amount of space to force man back into his savage state. J.M. Barrie shows one such circumstance in Peter Pan. The Darlings, a middle-class family in Bloomsbury, England represent a sophisticated society. Peter Pan, captain of the Neverland, is from the same lifestyle, but is a savage once he gets away from a sophisticated society, and the Darling kids turn savage likewise as they spend time in the Neverland. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies is also a two-society story. When there is a separation of societies, one savage and one sophisticated, someone in the savage society is forced to take on responsibility. Either he will grasp it and fight over it, or he will try to throw away any idea of responsibility. Either way, someone has to take on responsibility, for it is the very nature of humans. In the end, despite how responsibility is accepted in the savage society, the two societies must again intertwine. In J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, there is a distinct society portrayed in the opening scene. First described are Mr. and Mrs. Darling, who want children very much. When Wendy, their first child, came, “it was doubtful whether they would be able to keep her, as she was another mouth to feed” (Barrie 2). It is here where Barrie first gives a glimpse of a society many can readily identify with, that of the middle class. He describes the Darling house as “so nondescript . . . ‘you may dump it down anywhere you like, and if you think it was your house you are very Hulsey 2 probably right’ (87) . . . Barrie assumes that members of his audience recognize and identify with it because they, like the Darlings, are middle class” (Wilson). He goes on to explain, “Mr. Darling was frightfully proud of [Wendy], but he was very honourable, and he sat on the edge of Mrs. Darling's bed, holding her hand and calculating expenses . . .” (Barrie 2-3). The Darlings had to calculate whether or not they could keep Wendy, and had to calculate just the same for the two children who came after. “There was the same excitement over John. And Michael had an even narrower squeak; but both were kept . . .” (Barrie 3-4). This information “tells us that the Darlings are not flush” (Wilson) and that the Darlings are a middle class family. This is the first society that Barrie portrays in Peter Pan, and it defines the sophisticated society from which Peter and the lost boys have been separated. Once Mr. and Mrs. Darling have left to a party, Peter enters the nursery to try to find his shadow. He meets Wendy while he is trying to get his shadow to stick to his feet. Wendy sews Peter’s shadow back on for him and Peter forgets “. . . that he owed his bliss to Wendy. . . . ‘How clever I am,’ he crowed rapturously, ‘oh, the cleverness of me!’” (Barrie 26). Peter is amazed by his own cleverness, as he believes he got his shadow to stick by himself. Barrie says “. . . there never was a cockier boy” (Barrie 27). Since Peter is so “egocentric,” it gives him “freedom from time, responsibility, and any concept of togetherness . . .” (Wolf). Peter is satisfied with being free from such things, he indirectly discloses to Wendy. When Wendy asks, Peter admits that he does not know how old he actually is. He just tells Wendy he is “quite young” (Barrie 28) and goes on to explain that he ran away the day he was born: “It was because I heard father and mother,” [Peter] explained in a low voice, “talking about what I was to be when I became a man.” He was extraordinarily agitated now. “I don’t want ever to be a man,” he said with passion. “I want Hulsey 3 always to be a little boy and to have fun. So I ran away to Kensington Gardens and lived a long time among the fairies.” (Barrie 28) Peter admits indirectly that he does not ever want to have to be responsible. He ran away because he did not want to get caught in a world where he must grow up and face what every adult must face at one point or another. “Peter Pan readily resists the threat to freedom and self expression that grown-ups pose for children under the guise of solicitude” (Murray). He does not want to grow up because he wants to always have the freedom to do whatever he wants, uninterrupted by responsibilities, which so often get in the way of fun. Wendy continues to question Peter on Neverland and soon they come to the topic of the lost boys. Peter explains, “‘[The lost boys] are the children who fall out of their perambulators when the nurse is looking the other way. If they are not claimed in seven days, they are sent far away to the Neverland to defray expenses. I’m captain’” (Barrie 31). It is characteristic of Peter to be captain of the lost boys, although it is against his reason for running away. Peter is captain of a group of boys who all fell out of their prams and remained unclaimed for a week, which shows their parents’ neglect (Murray). The lost boys are an ideal group for Peter to captain because they know nothing of responsibility save what Peter shows them. Peter, on the other hand, knows how to be somewhat responsible. By taking up the position of captain, he has also become a role model for the boys: a father figure. He has gone against his very reason for being by unconsciously taking that little bit of responsibility. The reason Peter Pan goes to the Darling’s window is to listen to the stories that Mrs. Darling tells to her children before they go to bed, and he readily lets Wendy know that is his reason. He admits, “‘you see, I don’t know any stories. None of the lost boys know any stories’” (Barrie 32). When Wendy tells Peter that she knows plenty of stories, Barrie states, “. . . there Hulsey 4 can be no denying that it was she who first tempted him” (Barrie 33). Wendy is unconsciously inviting herself to Neverland to play as mother to the lost boys. At first, Wendy thinks she will not fly away with Peter, but he is “captain” of the lost boys and he is described often by Barrie as cunning, so he figures out how to convince her. “[Peter] had become frightfully cunning. ‘Wendy,’ he said, ‘how we should all respect you’” (Barrie 34). Peter goes on, in his cunning way, to describe all the chores that a mother would normally go about doing, and Wendy is soon “wriggling her body in distress. It was quite as if she were trying to remain on the nursery floor” (Barrie 34).Wendy is, even at such a young age, ready to become a mother. She is ready to obtain the responsibility that she plays at with her brothers. Wendy, John, and Michael fly off with Peter to the Neverland, and they are charmed by the lost boys and their careless way of living. They are charmed by the adventures and the games. John and Michael are more easily influenced and irresponsible than Wendy. “Soon Wendy has established a peculiarly childlike version of parental domestic order . . .” (Murray), and she is “mother” to all the lost boys, including Peter. Wendy takes some of the sophistication of her home to the Neverland, essentially ruining the sanctity of this “boy’s world” (Wilson). Wendy takes the responsibility of adulthood and parenthood to the Neverland, because “in Never Land, the parental figures—Mr. and Mrs. Darling—are left behind . . .” (Wilson). Wendy takes the responsibility that Peter so easily shuns and forgets, because Wendy has not yet turned into the savage that Peter and the lost boys and even Wendy’s own brothers are replicas of. The lost boys like blood “as a rule” (Barrie 53), and John and Michael have since forgotten that they ever had a mother other than Wendy. Wendy is the last inkling of sophistication in Neverland now, she “provides the civilizing influence . . .” (Springer), and thus she is left with the responsibility. Hulsey 5 Peter tries hard to please Wendy, and takes her to the mermaid’s lagoon. She wanted to see a mermaid; that was one of her main reasons for going to Neverland with Peter. When Peter, Wendy, and the lost boys are swimming in the lagoon, pirates show up, captained by James Hook. Peter is able to mimic Hook’s voice and soon gets himself into a squabble with Hook. Hook tries to guess who Peter is and begins to play a game with Peter. This gives insight into Hook’s own childlike manner. “Given that a theatrical convention is to have the role of Captain Hook played by the actor performing the role of Mr. Darling . . . Mr. Darling might be read as a figure in Never Land who escapes the pressures of being an adult by donning the guise of Captain Hook . . .” (Wilson). Hook is irresponsible and, essentially, still a child, which is perhaps why he is in Neverland. Hook, in his guessing game with Peter, tries to narrow his suspicions of who it may be speaking back to him in his own voice. He does this by asking Peter yes or no questions, which Peter answers with the playful gaiety of a child. Hook does not guess, but Peter gives himself away. Hook fights Peter as the lost boys fight the rest of the pirates. The lost boys take the pirate’s dinghy and Wendy floats off holding on to the tail of a kite. Peter is left on Marooner’s Rock, believing that he cannot fly or swim because he had been hit by Hook in their fight: Peter was not quite like other boys; but he was afraid at last. A tremour ran through him, like a shudder passing over the sea; but on the sea one shudder follows another till there are hundreds of them, and Peter felt just the one. Next moment he was standing erect on the rock again, with that smile on his face and a drum beating within him. It was saying, “To die will be an awfully big adventure.” (Barrie 101) Hulsey 6 “[Peter] lives only in the present and, consequently, he lacks deep human sympathy because he can learn nothing from experience” (Murray). Peter is a child with no memory. He is unintelligent enough to forget what he had learned previously in his life, and he accepts everything he thinks is new with the wide eyes of a child. By saying “To die will be an awfully big adventure,” Peter is pulling himself to his most respectful. He is accepting the fact that he is mortal. However, Peter is not sad about death. He looks at it as just another adventure. This is why Peter so soon gave up most of his responsibility to Wendy. He is just a boy. He is not ready to be a man, especially a father. He is far too savage to even begin to think it may be beneficial to grasp responsibility and simply grow up. With Wendy as a mother and the lost boys as his children, Peter is supposed to be an authority figure. He is, to an extent. He is called “father” and “captain,” but the lost boys know better than he what is pretend and what is real, and they often get the better of Peter. The lost boys also complain to Wendy about Peter’s faults. “Secretly Wendy sympathized with them a little, but she was far too loyal a housewife to listen to any complaints against father. ‘Father knows best,’ she always said, whatever her private opinion must be” (Barrie 108). Wendy is loyal to Peter as a housewife should be, although her private opinion must be one of disappointment. Wendy knows what Peter is. He is “heartless,” as Barrie so often describes children. Peter is so heartless that “even his mothers are interchangeable” (Murray). Peter will do anything to be able to be a child forever, even if that means breaking heart after heart in little girls, generation after generation. Peter Pan is a child, and that is what he will forever be, because he is so afraid of growing up and having to join the civilized society that will continue to steal mothers away from him forever. Eventually, Peter confronts Wendy about the nature of the mock family they put together. Hulsey 7 “I was just thinking,” he said, a little scared. “It is only make-believe, isn’t it, that I am their father?” “Oh, yes,” Wendy said primly. “You see,” he continued apologetically, “it would make me seem so old to be their real father.”(Barrie 113) Peter is afraid of Wendy’s answer, because he wants her to stay. He is ignorant of the feelings Wendy, Tinker Bell, Peter’s fairy, and Tiger Lily, the daughter of the Indian chief, hold for him. He does not know what love is, because he is savage. He believed Wendy in the beginning of the story that “thimble” meant “kiss” and vice versa. He believes anything that anyone tells him, and this way he is easily fooled. He may be captain and father to the lost boys, but he is not at all ready for such titles. Peter is only the captain of the lost boys because he has unlimited capacity for belief and imagination. Peter was most probably the first boy in Neverland and will be the last. His Neverland is more vivid and real than the Neverlands that children dream up, but Neverland, “as its name implies, doesn’t exist, save in the imaginative rendering . . . .It is a place of play within a play” (Wilson). Peter is the captain of the lost boys in their adventures, but Wendy is essentially their captain in the home under the ground, where they live. The lost boys accept Wendy readily, as mindless savages are likely to do. They do not question her authority, nor Peter’s. The lost boys, who now include John and Michael, are the savage society Barrie portrays in his novel. Peter, as the captain of such a group, is the main savage; he looks at life not as an adventure but as a game, and he is heartless and innocent. Wendy decides she wants to go back home, to Bloomsbury, because she does not want to forget her family. Peter has scared her into thinking that her parents would shut the nursery window they flew out of. Wendy, not wanting this to happen to anyone, asks the lost boys to go Hulsey 8 with her. They all agree, and Wendy believes that this means Peter is going as well. Peter, instead, stays in the home under the ground and arranges for Tinker Bell to bring them back to Bloomsbury. “The island . . . represents an earthly paradise in the children’s novel” (Wolf), and Peter is contented with giving up his possible adult life for the paradise of the Neverland. Wendy and the lost boys are captured by the pirates, and Peter soon goes after them, determined to rescue Wendy, for it is an adventure, and Peter cannot resist adventures. Peter starts ticking like the crocodile that Hook fears, for the clock in its belly had finally run down. “‘How clever of me,’ [Peter] thought at once, and signed to the boys not to burst into applause” (Barrie 155). He is a cocky boy with no humility, and he does not take into account at all that the boys would refrain on their own from clapping for his cleverness. Peter does not risk his life to save the lost boys, or even to save Wendy. He risks his life for an adventure, for he had made a “terrible oath: ‘Hook or me this time’” (Barrie 143), as he made his way to the ship. Peter is not showing responsibility in his rescue. He is showing boyishness, naivety, and carelessness. He is being clever, but his cleverness is coming from luck, not thought, and he is not at all careful. Peter and Hook fight, and finally Hook is defeated, but not before he calls Peter what he really is, a “‘Proud and insolent youth’ . . .” (Barrie 162). The pirates abandon their ship, showing that in Neverland, “. . . youth gain the upper hand over age” (Springer). Wendy does not see this as a good thing, and she still wants to go home. Wendy realizes that “. . . a lost paradise is a small price to pay for a heart and the capacity to love” (Wolf). The lost boys take the ship under their control, and “It need not be said who was the captain” (Barrie 167). Peter is able to keep the ship a pirate’s ship. Many of the boys “wanted it to be an honest ship . . . but the captain treated them as dogs, and they dared not express their wishes to him . . .” (Barrie 168). The lost boys are still savage, mindless children, although they are on their way back to sophistication. Hulsey 9 Peter arrives at the Darling’s house before Wendy and the lost boys show up. He flies into the window with Tinker Bell and bars the window. He does not want Wendy to be able to get back into the nursery. He wants to have Wendy to himself. Peter willingly goes back to the society that he tries so hard to distance himself from in his imagination every moment. He does this while Mr. and Mrs. Darling are asleep, and it is cowardly. Peter may be full of adventures and imagination, but when it comes to matters of the heart, matters which he knows nothing about, he is far from brave. Peter is angry with Mrs. Darling, because he believes she does not realize why she cannot have Wendy back. “The reason was so simple: ‘I’m fond of her too. We can’t both have her, lady’” (Barrie 174). Peter wants Mrs. Darling to give Wendy up, just as his own mother gave him up: But the lady would not make the best of it, and [Peter] was unhappy. . . . He skipped about and made funny faces, but when he stopped it was just as if she were inside him, knocking. “Oh, all right,” he said at last, and gulped. Then he unbarred the window. “Come on Tink,” he cried, with a frightful sneer at the laws of nature; “we don’t want any silly mothers”; and he flew away. (Barrie 174-75) Peter shows compassion in the only way a child like him knows how: he refuses his own want, denying that he even wants Wendy to go with him. Peter, for once, shows a semblance of responsibility. He accepts, subconsciously, that it was his decision, countless years ago, to leave this civilization, and it is because of that decision that he must leave the nursery window open for Wendy. Peter is unable to change and unable to understand Wendy’s want for this sort of society. He believes that the society in the Neverland is the only society that makes any sense, but he Hulsey 10 nonetheless lets Wendy go home. Peter grasps responsibility in one moment that it would have been beneficial to him to stay savage. Wendy, John, and Michael enter the nursery and find Mr. and Mrs. Darling. It is the most heartwarming scene in Barrie’s novel, and he describes it simply. “There could not have been a lovelier sight; but there was none to see it except a strange boy who was staring in at the window. He had ecstasies innumerable that other children can never know; but he was looking through the window at the one joy from which he must be for ever barred” (Barrie 177). The Darling children are once again a part of sophistication, which they did not think of while they were in the Neverland, but which they now realize they missed. The lost boys come into the nursery and ask Mrs. Darling if she would take them in as her sons. The boys are accepted into the family with open arms and a cry of “Hoop la!” from Mr. Darling. All the boys, that is, except for Peter. Mrs. Darling wants to adopt him too, but Peter keeps out of arms reach of her. “‘I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things,’ he told her passionately. ‘I don’t want to be a man. . . . Keep back, lady, no one is going to catch me and make me a man’” (Barrie 180). Peter has given Mrs. Darling what she wants, her children, and in return all he wants is to be able to stay the way he is. He is not going to join the world of schools and offices with the other boys, even though his decision would keep him from Wendy. Peter is, after all, just a child, and with his perpetual childhood comes irresponsibility and no ability to love. Wendy, Peter, and Mrs. Darling strike a deal which allows Wendy to join Peter to the Neverland for a week every year to do his spring cleaning. Barrie tells of the lost boys, how they “saw what goats they had been not to remain on the island; but it was too late now, and soon they settled down to being as ordinary as you or me or Jenkins minor” (Barrie 182). The societies of savagery and sophistication merge here, with the lost boys, and the boys are soon just ordinary. Hulsey 11 They are no longer savage children who live for adventure. The lost boys lose their savagery with their ability to fly and their belief in Peter Pan and the Neverland. Civilization tames their savage impulses and puts proper manners where their imaginations used to be. This is the first way in which Barrie’s two civilizations intertwine. The sophisticated society wins against the savage society with the lost boys, but the two societies merge again in a different way. Peter takes Wendy back to the Neverland only a few times before she is grown, married, and a mother. Peter wants to refuse that Wendy has grown up. He is afraid of Wendy and draws away from her when she tries to hug him. After a while, Peter accepts that Wendy’s daughter Jane is asleep in her old bed “and he took a step towards the sleeping child with his dagger upraised. Of course he did not strike. He sat down on the floor instead and sobbed . . .” (Barrie 189). Peter does not understand the truth of growing up. He does not understand the society in which his “mother” lives. He thinks it is Wendy’s own fault she grew up, but unlike Peter, she could not choose to not grow up. Peter takes Wendy’s daughter Jane to Neverland with him to be his mother. Peter will try this forever−try to get one of Wendy’s descendants to go with him to the Neverland and stay with him there forever, to be his mother forever. But these girls, Wendy’s descendants, are too sophisticated and too educated to stay forever with him. Peter goes back every year that he remembers and takes whichever little girl is there, be it Wendy or Jane or Margaret, Jane’s daughter, or any of the following descendants, “and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless” (Barrie 192), which is just what Peter is, the epitome of childhood. Peter will forever be the savage that can be found in the Neverland, “the fantasy of boyish adventure . . . and idealization of what never was . . .” (Wilson). He will continue to try to bring a mother to Neverland and keep her there forever, but it will not happen. “Peter’s tale is essentially unresolved because he never changes. The story is also never ending because he returns Hulsey 12 generation after generation for a new ‘child mother’” (Murray). Peter will forever be the conflicting society, the savage that lives on forever, a symbol of human nature and irresponsibility. He is the main savage in Barrie’s novel—the perfect picture of a child. Barrie’s two societies will forever be separated—though they may intertwine from time to time—because there will always be children, the savages of the world, and adults, the sophistication. In Lord of the Flies, William Golding describes societies different than the two in Peter Pan. Unlike Barrie’s, Golding’s two societies are largely made up of the same group of people. Previous to the beginning of Golding’s novel, a group of schoolboys survive a plane crash that the adults on the airplane did not survive. Golding’s sophisticated society begins as every person in his book. The boys stranded on the island and the pilot who died in the plane crash all come together to make up this society. Since the boys are on an island, away from physical signs of civilization, they are a separated society. Lord of the Flies opens with Ralph stumbling over rocks and tearing his way through the jungle. Ralph’s struggle with the jungle is at first a contrasting of Ralph’s society and that of the island, but second it is a way to compare Ralph to the jungle. Already Ralph is sweating and finding his way through the jungle as though he has been doing it his entire life. Here, “man is within the world of savagery and blood-lust . . . woefully ill-equipped to deal with the world which faces him” (Selby). Golding describes Ralph without bias. “He was old enough, twelve years and a few months, to have lost the prominent tummy of childhood and not yet old enough for adolescence to have made him awkward. You could see now that he might make a boxer, as far as width and heaviness of the shoulders went, but there was a mildness about his mouth and eyes that proclaimed no devil” (Golding 10). Ralph is just a boy, lost in a jungle on an uninhabited island. Ralph meets a boy he does not know, and asks his name. The boy replies, “‘They used to call me “Piggy”’” (Golding 11). Ralph Hulsey 13 laughs at this and ignores it when Piggy, as he is called from now on, asks him to stop yelling it; he doesn’t want anyone else to know. Ralph and Piggy are children. They have yet to grow up and mature. This is Golding's first society, his sophistication. Ralph and Piggy find a conch shell and Piggy suggests blowing the conch to signal any other boys that may be on an island. This is where Golding introduces Jack Merridew and his choir. Jack is described as “thin, tall, and bony; and his hair was red beneath the black cap. His face was crumpled and freckled, and ugly without stillness. Out of this face stared two light blue eyes frustrated now, and turning, or ready to turn, to anger” (Golding 20). Jack is in no way as threatening or respectful-looking as Ralph is, but his voice is said to contain “off-hand authority” (Golding 21). Boys of all shapes and sizes join Ralph and Piggy on the platform they are on. Soon enough, Ralph suggests that they elect a chief. “'I ought to be chief,' said Jack with simple arrogance, 'because I'm chapter chorister and head boy. I can sing C sharp'” (Golding 22). Ralph wants order; he wants to be the civilized boy he was at home. Golding's novel “. . . asks whether such children will re-create the democratic civilization they have experienced during their short lives or instead, because of animal survival instincts, revert to some precivilized form of existence” (Shields). Ralph is trying to create the democracy he was raised in. He wants to be sophisticated and he wants to be rescued. This is why he suggests they elect a chief. In the end, the boys decide to vote for who they want to be chief. “. . . what intelligence had been shown was traceable to Piggy, while the most obvious leader was Jack. But there was a stillness about Ralph as he sat that marked him out: there was his size, the attractive appearance; and most obscurely, yet most powerfully, there was the conch” (Golding 22). Ralph is voted chief and he decides to make Jack and his choir hunters. He asserts his responsibilities as chief first to give himself some respectfulness, and second to show Jack that he will not be able to win the Hulsey 14 responsibility from him. Jack and Ralph, from the vote on, are battling for the respect of the boys on the island in the form of responsibility and the title of chief. Jack turns out to be a better hunter than he would make a chief. He is passionate about the chase. However, when the hunters capture their first pig, they do not kill it. It gets away. Ralph asks why Jack didn't kill it. “They knew very well why he hadn't; because of the enormity of the knife descending and cutting into living flash; because of the unbearable blood” (Golding 31). They are still the sophisticated children they were before the plane crash. Jack is a “noble beast able to impose himself upon his surroundings, and to reason and act on that reason” (Selby). He knows that he can take life from a pig, but he cannot do it because he is “noble.” “‘We’ve got to have rules and obey them. After all, we’re not savages. . . . so we’ve got to do the right things’” (Golding 42). This is the first time any of the boys directly acknowledges that they are any more sophisticated than the animals they hunt on the island. Jack brings this realization to the boys bluntly, asserting his right to speak in the mock democracy Ralph has tried to create. Jack tries to get in Ralph’s way, because he wanted to be chief. Jack does not let Ralph have all the control. Jack is chief of his hunters, but he is under Ralph, and this makes him unhappy. Jack wants all the power; he wants Ralph to have none of it. Jack is going to fight with Ralph over the title of chief for the rest of their stay on the island. Jack goes out to hunt by himself and sends his hunters back to the beach to help Ralph and Simon build shelters. Jack returns to the beach without having killed a pig. Ralph is angry at him for having gone out without first finishing the shelters and at his hunters for playing and swimming instead of helping. Jack makes excuses for himself, and tries “to convey the compulsion to track down and kill that was swallowing him up” (Golding 51). Jack was hunting for hours, sweaty and gross, because he thought it was worth it to be able to kill. “. . . Lord of the Hulsey 15 Flies focuses on the psychology of its characters . . .” (Wolf), and since Jack cannot quite convey to Ralph and the others why he is so obsessed with hunting, he is “. . . baffled by what he cannot physically control” (Selby). Jack wants to be a man, but he does not want to be a sophisticated man. He wants to be a hunter, a predator. He wants to be the dominant species on the island, and within that species, he wants to be the leader. Jack is so used to being the leader of his choir group that he believes he is the obvious leader of the island. When he is denied that right, Jack does not know how else to vent his anger than to hunt. Jack passes on his obsession for the hunt with his choir, now his hunters. “. . . the obsession with the hunt transforms the hunters into a nameless group that functions conjointly but without personal identity . . .” (Dick and Bloom). The hunters are soon just like Jack, but under him. They are all one “organism” that functions on Jack’s thoughts. When there is no thought going into action, there is savagery. The hunters paint themselves with clay, a symbol of the change they undergo. “[Jack] capered toward Bill, and the mask was a thing on its own, behind which Jack his, liberated from shame and selfconsciousness” (Golding 64). The masks of clay the hunters paint on themselves signal their change from sophistication to savagery. This is the second society that Golding portrays in his novel, these savage boys who used to be the most obviously sophisticated on the island. As chief, Ralph asserts the need for a signal fire. When two of the boys, the twins Sam and Eric, let the fire go out, Ralph is furious. He makes the boys rebuild the fire and does not help: No one, not even Jack, would ask him to move and in the end they had to build the fire three yards away and in a place not really as convenient. Hulsey 16 So Ralph asserted his chieftainship and could not have chosen a better way if he had thought for days. Against his weapon, so indefinable and so effective, Jack was powerless and raged without knowing why. (Golding 73) Ralph knows he is chief and that the boys will listen to him, but he is tired of the boys refusing his orders when he is not around. He is not threatening to them, for they know they outnumber him greatly, but they listen, because they still have that small piece of civilization stuck inside their minds. Like Wendy in Peter Pan, the boys have brought their own sophistication to the island. They have not forgotten completely what they used to be. Unlike Wendy, however, these boys are “. . . always near to slipping into barbarity . . .” (Selby). They are, however, still boys. Around the fire Ralph had the boys make, Jack and Ralph stopped fighting, and “. . . unkindness melted away. They became a circle of boys round a campfire . . .” (Golding 73). Because of their naivety, like in Peter Pan, these boys easily return to the savage state man was in thousands of years ago. One of the younger boys, a littlun, says that there is a beast on the island, one that comes out of the sea. Soon, Samneric, the twins, claim to have seen the beast on the mountain they had the fire built on. Golding reveals to the reader that this “beast” is a dead man with a parachute. The parachute catches the wind and makes the man seem to move. Again Samneric let the fire go out on top of the mountain. This time, Ralph gives them a chance to explain themselves, and when they do everyone on the island is spooked. They are afraid of the beast. “I know there isn't no beast—not with claws and all that, I mean—but I know there isn't no fear, either.” Piggy paused. “Unless--” Hulsey 17 Ralph moved restlessly. “Unless what?” “Unless we get frightened of people.” (Golding 84) Piggy is aware that there is not a beast on the island and that the only thing they have to be afraid of is themselves, because they are reverting to savagery. “'What are we? Humans? Or savages? What's grownups going to think? Going off—hunting pigs—letting fires out—and now!'” (Golding 91). Piggy knows that they are changing into savages. Piggy is the same kind of character Wendy is in Peter Pan. He is the rational, sophisticated thinker, the only hint of a sophisticated civilization on a savage island, especially after Ralph goes hunting with Jack and his hunters. Ralph throws a spear at a pig and wounds it, and all the boys cheer for him. “He sunned himself in their new respect and felt that hunting was good after all” (Golding 113). Ralph, after all his opposition to the hunters and Jack, is easily drawn into their hunt. Ralph is drawn to savagery because it is fun and fast paced and just what a boy his age is looking for. Like Peter, Ralph and the other boys in Lord of the Flies want adventures. They want what they cannot get in their old society. Jack, after a particularly nasty argument with Ralph over the nature of the beast and the importance and unimportance of shelters and hunters, decides that he will leave and make his own tribe. His hunters go with him and many of the older boys follow. “'We'll hunt. I'm going to be chief'” (Golding 133), Jack says. He does not give his hunters a say in it. Jack goes through this sort of trouble just to be able to taste the responsibility that Ralph had from the very beginning. They will do what he says, just as the lost boys would do anything that either Peter or Wendy said; they are only children, and they are looking for the most fun and the least work. Savagery is just that. Jack takes his new tribe out to hunt, and they go with him without question. Hulsey 18 Jack is the dictator of their group, a kind of king. Unfortunately for the boys, “. . . the only kings are mock ones such as Jack . . .” (Wolf). Jack has no idea what he is doing. He is doing everything according to what his instinct tells him to do. Soon the boys are on a hunt, following a wounded sow. “. . . the sow staggered her way ahead of them, bleeding and mad, and the hunters followed, wedded to her in lust, excited by the long chase and the dropped blood” (Golding 135). The sow they are following excites them, because they know they can take her life if they get close enough. They know they are the dominant species. Because of this, the boys are wild, irrational, and quick. They do not think of the piglets the sow had just been nursing, only about the chase. They do not care about the meat they will get, only about the blood that is being dropped by the running sow. The boys that follow the pig on the wild hunt are no longer the boys they used to be. Now they are savages with sharpened sticks running wildly after a pig. They are a society separated from another that is trying its best to become moderately civilized. Ralph's tribe consists of only Piggy, Samneric, and Simon, a quiet boy who helped Ralph build shelters while every other boy played or hunted. These five are left with most the small children, the “littluns,” and a signal fire that is too big for them to keep up. Ralph has “[proved] incapable of maintaining rules and order” (Wolf); he is not the successful chief he tried to be. He tried to keep a signal fire going so they might be rescued, but the boys soon saw the adventure of hunting, the fun of savagery, as more important. Now Ralph is left with a small mockery of a democracy and no hope of rescue. Ralph admits to Piggy that he does not care much about the fire anymore and doesn't care about rescue like he used to. Ralph also loses his persuasive ability when he speaks. Soon he is forgetting why he wants a fire, and Piggy has to cue him. Ralph is not much better than Jack and his tribe in mentality, but Ralph is persistent and tries his hardest to do what is right. He is not quite yet a savage. Hulsey 19 Simon believes Ralph and Piggy, and he is in agreement throughout the entire novel that they should have a chief and that they should vote and discuss issues. Simon goes out into the jungle and comes face to face with the head of a sow the hunters had put on a stick as a gift to the beast. It is here that “Simon . . . recognizes that the 'beast' the boys fear actually is located within the boys themselves” (Shields). Simon realizes that there is nothing on the island to be afraid of save the boys themselves, the savages. Simon goes onto the mountain to see the physical beast that scared Samneric so badly and he sees it for what it really is, a corpse of a man. “Confronted with the non-rational, Simon recognizes it, for it is an 'ancient, inescapable recognition.' But such recognition brings either a loss of innocence or death . . .” (Dick and Bloom). In Peter Pan when Wendy recognizes the irrationality of Peter's life, she loses some of her innocence by taking her brothers and the lost boys home. Likewise, Simon loses his innocence and becomes a symbolic beast. “A thing was crawling out of the forest. It came darkly, uncertainly. . . . The beast stumbled into the horseshoe. . . . The blue-white scar was constant, the noise unendurable. Simon was crying out something about a dead man on a hill” (Golding 152). During this, the boys are chanting, “Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood! Do him in!” (Golding 152). Simon is murdered by the boys and all the while he is trying to explain to them what the beast was. Simon tries to save the boys from themselves by telling them that there is nothing to be afraid of, but he is quickly killed, a symbol of the death of sophistication within Jack's tribe. Ralph, Piggy, and Samneric try to keep their own tribe with the littluns on the side of the island opposite where Jack's tribe is. Jack and his tribe are without fire with which to cook the pigs they hunt down and kill for food. To solve this problem they first steal a branch with fire on it and then Piggy's glasses. The boys had figured out that Piggy's glasses would crate a fire in the Hulsey 20 beginning of the novel. Because of this, Ralph, Piggy, and Samneric go to castle rock, where Jack's tribe stays, and try to ask for Piggy's glasses back. Jack had figured out a way to make weapons to keep Ralph and his tribe out of Jack's way. “A log had been jammed under the topmost rock and another lever under that. Robert leaned lightly on the lever and the rock groaned. A full effort would send the rock thundering down to the neck of land. Roger admired. 'He's a proper chief, isn't he?'” (Golding 159). Golding's novel is “a vision of youth and humanity as innately more cruel and savage than loving and civilized . . .” (Wolf). Jack is, essentially, the main savage. He has been a savage-type since the plane crash stranded the boys on the island, but now he is able to show it. “He was a chief now in truth . . .” (Golding 168). Jack is glad to be chief of the savages. He could not get his way in the beginning, so he got his way in the end. He uses his knowledge of the sophisticated society they all used to be a part of to win himself a tribe. Unlike Peter Pan, Jack wants this responsibility, he fights for it. He is not attractive and innocent like Peter. Instead he is cruel and savage. When what is left of Ralph's tribe goes to castle rock to retrieve Piggy's glasses, Ralph notices the boys. “Savages appeared, painted out of recognition, edging round the ledge toward the neck” (Golding 175). Ralph could not recognize any of the boys he used to know and lead. He is the enemy on the other side of the weapon. Piggy tries to make order when the boys started booing at Ralph, but Piggy is killed and the conch is shattered. “'See? See? That's what you'll get! I meant that! There isn't a tribe for you anymore! The conch is gone— . . . I'm chief!'” (Golding 181). Jack is afraid of the conch and what it represents. The hunters, as savage as they may seem, recognize the conch and respond to it in Ralph's favor. When the conch is broken, Jack is brave, for there is no longer anything working against him. His hunters are now his alone, his responsibility. It is Jack's goal to “. . . destroy the rational element . . .” (Dick and Bloom) by destroying anything that gets in his way. Hulsey 21 The only thing left after the conch is destroyed is Ralph. Jack must destroy his last opposition so he may be responsible for all of the boys on the island, like he wanted since the beginning. Samneric become part of Jack's tribe, Ralph finds out. Ralph has run away and hidden from Jack's tribe, because Jack wants to kill him. Ralph tells Samneric his plan to escape Jack and his tribe, trusting them with the secret, but Samneric tell Jack. Soon, Ralph is on the run from every boy left alive on the island. Jack tries to smoke Ralph out of his hiding spot and soon the entire island catches fire. “The lovely place which is the setting of Golding's novel becomes a hell of the boys' own making” (Wolf). The boys have destroyed their own food supply by burning the fruit trees, and the only thing they are concerned about is Ralph. Ralph, on the other hand, is not as concerned with finding the savages. He is running and trying to decide how to hide. “He had even glimpsed one of them, striped brown, black, and red, and had judged that it was Bill. But really, thought Ralph, this was not Bill. This was a savage whose image refused to blend with that ancient picture of a boy in shorts and shirt” (Golding 183). Ralph realizes, finally, that these boys are not the boys he knew. They have changed. Ralph never really lost his chieftainship; instead he lost his tribe. The boys he used to know have disappeared, and they will not be found. As much as Ralph tried, good did not win over evil. “. . .it is not even effective. The potential of innocence for heartlessness implied in Peter Pan is here explicit” (Wolf). The boys who chase after Ralph are heartless things. To Barrie, it is a given that the children in the book will be heartless, but to Golding, it is something that takes some time to develop. There is no sense in this tribe anymore, even in Ralph. He, like the other boys, finally turns savage. “He raised his spear, snarled a little, and waited” (Golding 194). Ralph is only trying to protect himself, but in doing so he turns into something no more intelligent than an animal: a savage. In the end, Ralph becomes just what he and Piggy were trying to prevent. Hulsey 22 Ralph is not caught by Jack and his tribe. He gets as far as the beach and there he stops in front of a navy man. The rest of the boys likewise stop when they see him. The navy man looks at them and believes they were just playing war. Ralph tells him two people died that they know of: “Are there any adults—any grownups with you?” Dumbly, Ralph shook his head. He turned a half-pace on the sand. A semicircle of little boys, their bodies streaked with colored clay, sharp sticks in their hands, were standing on the beach making no noise at all. “Fun and games,” said the officer. (Golding 200) Golding describes this scene as the naval officer sees it. The savages that killed two kids and pursued another without sparing a thought for the consequences are here described as little boys. The views of the naval officer differ so greatly from Golding's previous description of the boys to demonstrate the reemergence of a sophisticated society. The naval officer believes that the boys were doing what boys do, playing war and having fun. He believes that the boys were peaceful. The officer “comes to the rescue and resolves the action . . .” (Dick and Bloom), however, the officer's appearance and calmness is ironic when placed next to the previous bloodshed of the tribes (Dick and Bloom). The naval officer asks who is in charge and right away Ralph speaks up, saying that he is. “A little boy who wore the remains of an extraordinary cap on his head and who carried the remains of a pair of spectacles at his waist, started forward, then changed his mind and stood still” (Golding 201). Ralph takes the responsibility he had lost from Jack when it really mattered, when they are again one tribe and they are faced with a society they do not know. Jack does not say anything because he is not sure how to talk to a sophisticated being. The two societies finally meet again, and there is only stunned silence. “And Hulsey 23 in the middle of them, with filthy body, matted hair, and unwiped nose, Ralph wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man's heart, and the fall through the air of the true, wise friend called Piggy” (Golding 202). Ralph cries not out of happiness and relief, but because the boys around him are no longer boys, because the naval officer does not care about the two dead but only about how the boys failed to take good care of each other, and because Piggy, the only one on the island who would have succeeded in remaining sophisticated, is dead. Both Peter Pan and Lord of the Flies are stories about boys who somehow escape to islands, far away from civilization. Both novels are about innocence and losing it. However, these two novels are different. In Peter Pan, good triumphs over evil, and the children get home safe. In Lord of the Flies, the savage side of man prevails, working its way into not only the boys of the island, but also the navy man who comes to take them away. Both these stories are never ending. Peter returns to the Darling's window every year he remembers, and the navy man turns away to let the boys regain control of themselves. These two novels are stories about children and the savagery they hold. Neither Peter nor Jack truly change into a savage. They were both already savage. Golding and Barrie both define childhood as temporary savagery, traits that will be pushed into the back of the mind by sophistication. However, savagery cannot be erased, and it takes barely any time at all for someone, or a group of someones, to revert back to that state of childhood, when adults are the enemy and war is just a game. When one returns to the state of savagery, innocence is gained once again, for savagery and childhood are one in the same. If innocence is gained, it must be lost, and that is the point at which a child becomes a young adult and sophistication and savagery intertwine into one society, in which children and adults are interchangeable for their attitudes. There will never, therefore, be a final convergence of these two societies, for there must be differentiation to be convergence. Hulsey 24 Works Cited Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan. New York. Penguin Books Ltd., 1987. Dick, Bernard F. and Harold Bloom. “Lord of the Flies and The Bacchae.” Literary reference center. 2005. Ebscohost. 14 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Golding, William. Lord of the Flies. New York. Penguin Books Ltd., 2006. Murray, Thomas J. “Peter Pan.” Literary Reference Center. 1991. Ebscohost. 13 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Selby, Keith. “Golding’s Lord of the Flies.” Literary Reference Center. 2002. Ebscohost. 13 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Shields, Agnes A. “Lord of the Flies.” Literary Reference Center. 1996. Ebscohost. 14 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Springer, Heather. “Barrie’s Peter Pan.” Literary Reference Center. 2007. Ebscohost. 13 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Wilson, Ann. “Hauntings, Anxiety, Technology, and Gender in Peter Pan.” Literary Reference Center. 2000. Ebscohost. 14 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Wolf, Virginia L. “Paradise Lost? The Displacement of Myth in Children’s Novels Set on Islands.” Literary Reference Center. 2002. Ebscohost. 14 November 2007 <http://web.ebscohost.com>.