Miranda v. City of Cornelius - Alameda County District Attorney's Office

advertisement

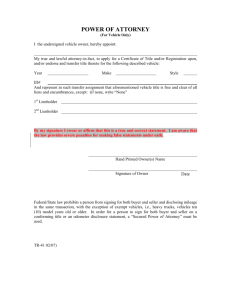

POINT OF VIEW Recent Case Report Miranda v. City of Cornelius (9th Cir. 2005) 429 F.3d 858 ISSUE Can officers impound a vehicle if impoundment was authorized by a statute but, under the circumstances, was unnecessary? FACTS Jorge Miranda was teaching his wife, Irene, to drive. Although Irene did not have a license or learner’s permit, she would drive the family car around their neighborhood in Cornelius, Oregon while Jorge supervised from the passenger seat. One day, Irene’s driving caught the attention of a Cornelius police officer who noticed that she was driving “poorly” and much too slowly for conditions. Suspecting she might be impaired, he turned on his overhead lights. Irene then pulled into the driveway of her home and stopped. The officer cited her for driving without a license, and cited Jorge for permitting an unlicensed driver to operate a vehicle. He then impounded the car pursuant to an Oregon statute permitting impoundment when the driver is unlicensed. After paying their fines, the Mirandas filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city of Cornelius claiming the impoundment of their car was unreasonable and, therefore, a violation of the Fourth Amendment. The district judge granted the city’s motion for summary judgment, and the Mirandas appealed to the Ninth Circuit. DISCUSSION The law permits officers to impound vehicles for a variety of reasons, most of which further some “community caretaking” purpose, such as removing vehicles that are impeding traffic or are illegally parked.1 In addition, impoundment may serve to protect See Veh. Code §§ 22651-22669; South Dakota v. Opperman (1976) 428 U.S. 364, 368-9 [“The authority of police to seize and remove from the streets vehicles impeding traffic or threatening public safety and convenience is beyond challenge.”]; Colorado v. Bertine (1987) 479 U.S. 367, 375-6; People v. Salcero (1992) 6 Cal.App.4th 720, 723 [“The officer could properly impound the car when he discovered defendant had no driver’s license.”]; People v. Scigliano (1987) 196 Cal.App.3d 26, 29 [“The Vehicle Code is not the only source of authority to impound a vehicle. Indeed, the police have a duty to protect a vehicle, like any other personal property, which is in the possession of an arrestee.”]; People v. Trejo (1994) 26 Cal.App.4th 460, 462-3 [“[T]he fact that the Fleetwood was not on a highway or public lands as specified in Vehicle Code § 22651(p) was not a basis for suppressing evidence under federal law.”]; U.S. v. Duguay (7th Cir. 1996) 93 F.3d 346, 352 [“Impoundments by the police may be in furtherance of public safety or community caretaking functions, such as removing disabled or damaged vehicles, and automobiles which violate parking ordinances, and which thereby jeopardize both the public safety.”]; U.S. v. Johnson (10th Cir. 1984) 734 F.2d 503, 510 [car was parked on private lot exposed to vandalism, and the 1 1 ALAMEDA COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE the vehicle and its contents from damage or theft if the car will be left in a public place after driver was arrested or incapacitated. Impounding a vehicle whose driver is unlicensed also usually serves a community caretaking purpose because most unlicensed drivers do not have sufficient training and experience to drive safely. And if the vehicle is not impounded, the driver may simply drive away after the officer leaves. Thus, Oregon, California, and probably most other states permit officers to impound vehicles under these circumstances.2 It would appear, therefore, that because the impoundment of the Mirandas’ car was authorized by statute, it was lawful. And that is what the city of Cornelius argued. The Mirandas’ argued, however, that mere statutory authorization is not enough—there must be reason to believe that impoundment serves some legitimate purpose. The court agreed, ruling that because the impoundment of a car constitutes a “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment, it must comply with the Fourth Amendment’s requirement of “reasonableness.” Consequently, the court examined the circumstances surrounding the impoundment of the Mirandas’ car and concluded there was no apparent need for it. As the court pointed out, the car “was not creating any impediment to traffic or threatening public safety.” Furthermore, there was no public safety threat because the car was legally parked and the registered owner was licensed and in control of the vehicle. In addition, Ms. Miranda had no reason to drive off after the officer left because the car was parked in the family’s driveway. As the court pointed out, “no such public safety concern is implicated by the facts of this case involving a vehicle parked in the driveway of an owner who has a valid license.” For these reasons, the court ruled that, even though the impoundment was authorized by statute, the city of Cornelius was not entitled to qualified immunity. Instead, the lawsuit should proceed to trial, at which time the city would be given an opportunity to “offer evidence of a legitimate government purpose for the impoundment sufficient to render the seizure reasonable.” COMMENT We received several phone calls and e-mails from officers who expressed concern that the Miranda decision meant that officers could no longer impound vehicles pursuant to California Vehicle Code § 22651(p) which, among other things, permits impoundment if the driver was cited for driving without a license in violation of Vehicle Code § 12500. There was, however, nothing in the court’s discussion that would warrant such an expansive view of its ruling. In fact, the court made it clear that it was dealing with an unusual situation involving “special circumstances” in which there was absolutely no community caretaking justification for the impoundment. Furthermore, the court seemed to acknowledge that in most cases there is usually good reason to impound vehicles whose drivers are unlicensed. Said the court, “An impoundment may be proper under the community caretaking doctrine if the driver’s driver was drunk]; U.S. v. Staller (5th Cir. 1980) 616 F.2d 1284, 1289-90 [impoundment reasonable where car was legally parked in mall lot but the arrested driver was from out of state and nobody else was available to assume responsibility]. 2 See Cal. Veh. C. § 22651(p) [impoundment permitted if driver was cited for driving without a license in violation of Veh. C. § 12500]; Or.Rev.Stat. § 809.720 2 POINT OF VIEW violation of a vehicle code regulation prevents the driver from lawfully operating the vehicle . . . ”3 For these reasons, and because most officers already exercise good judgment in determining when impoundment is and is not reasonably necessary, we do not think the Miranda decision should be interpreted as announcing a new rule. Still, the decision may serve as a reminder that, with the exception of forfeitures, vehicles may not be impounded for the sole purpose of punishing the driver or owner. POV 3 NOTE: Ironically, the impoundment of the Miranda’s car would not have violated the Fourth Amendment if the officer had taken Ms. Miranda into custody and searched it incident to her arrest. This is true even though Oregon law did not authorize a custodial arrest for driving without a license. See Atwater v. City of Lago Vista (2001) 532 U.S. 318; People v. McKay (2002) 27 Cal.4th 601, 618. 3