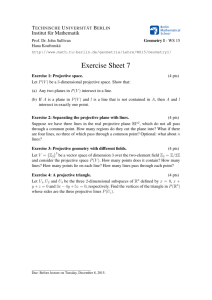

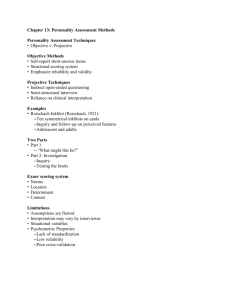

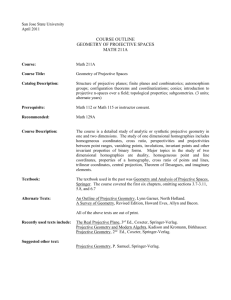

3-assessing-personality-with-projective-methods

advertisement