Rehabilitation and Redemption in Les Misérables

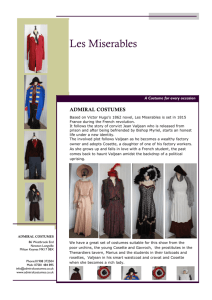

advertisement