A Review of Culture in Information Systems Research: Toward a

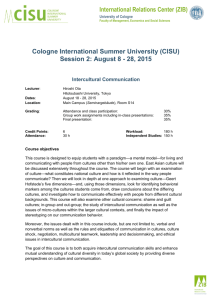

advertisement