Birmingham consequences - Northcote

advertisement

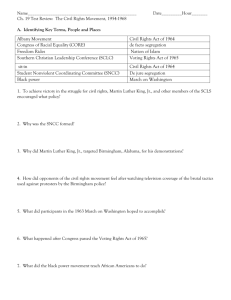

Birmingham Campaign: Consequences Read “Birmingham – the results”, p.48 Limited desegregation Despite the success of the campaign in crippling Birmingham economically, real progress was limited. Desegregation in Birmingham took place only slowly after the demonstrations had ended, despite the guarantees. Indeed, King and SCLC were criticized by some for ending the campaign with promises that were too vague and "settling for a lot less than even moderate demands". Under the agreement with the City, desegregation was supposed to take place within 90 days from May 15th. At the end of this period a single black clerk was hired: there was no hiring of the promised black police officers or firefighters. Despite this, by July most of the city's segregation laws had been overturned. Some of the lunch counters in department stores complied with the new rules, city parks and golf courses were opened again to black and white citizens, and Birmingham's public schools were integrated in September 1963. (Governor Wallace, however, sent National Guard troops to keep black students out but President Kennedy ordered the troops to stand down.) King/SCLC The reputation of Martin Luther King soared after the protests in Birmingham, and he was congratulated in many cities as a hero. SCLC rose to prominence as a national force in the civil rights arena where previously the older and stodgier NAACP and their legal approach had dominated. As such, SCLC was much in demand to bring about change in many other Southern cities. As for King himself, late that year (1963) he was one of the leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom [see p.59] where he delivered his famous ”I Have a Dream" speech. King became Time magazine's “Man of the Year” for 1963. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 [see p.60]. Federal action The Birmingham campaign, as well as Governor George Wallace's refusal to admit black students to the newly desegregated University of Alabama, convinced President Kennedy to address the severe inequalities between black and white citizens in the South: "The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased cries for equality that no city or state or legislative body can prudently [wisely] choose to ignore them." Kennedy's administration drew up the Civil Rights Act which was passed into law in 1964 [see pp.5960]. The Civil Rights Act applied to the whole nation, prohibiting racial discrimination in employment and in access to public places. Inspiration for other campaigns The Birmingham campaign inspired the Civil Rights Movement in other parts of the South. As noted below, Medgar Evers of the NAACP in Jackson, Mississippi, organized demonstrations similar to those in Birmingham. Elsewhere, local organisations and individuals were acting on the new mood of change. More and more whites were also becoming involved. Over 1600 marches and protests occurred in 1963 alone, directed mostly by local organisations rather than by national ones such as SCLC or SNCC. When long-time labour union leader A. Philip Randolph proposed a march on Washington, he argued in a June 1963 meeting with President Kennedy that "the Negroes are already in the streets. It is very likely impossible to get them off." Randolph assured Kennedy that the march would not increase grassroots militancy but would instead divert that militancy into safer channels: "If they are bound to be in the streets in any case, is it not better that they be led by organizations dedicated to civil rights and disciplined by struggle rather than to leave them to other leaders who care neither about civil rights nor about nonviolence?" In 1965 King and SCLC led further marches in Selma, Alabama, related to a voter registration drive. However, such civil rights protests were already declining in significance within the larger African-American freedom struggle. White backlash [See pp.52-54] Where blacks felt real hope in the lengthy struggle for civil rights, many whites felt that their way of life was under threat. On May 11th, a bomb destroyed the Gaston Motel in Birmingham where Martin Luther King had been staying earlier, and another damaged the house of King's brother. Four months after the Birmingham campaign settlement, someone bombed the house of NAACP attorney Arthur Shores, injuring his wife in the attack. On September 15th, 1963, Birmingham again earned international attention when Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and killed four young girls. In addition to this, Medgar Evers of the NAACP in Jackson, Mississippi [see above], was fatally shot outside his home. He had been organizing demonstrations similar to those in Birmingham to pressure Jackson's city government. Black backlash Some historians argue that the riots that occurred after the bombing of the Gaston Motel foreshadowed the rioting that occurred in larger cities later in the 1960s [see p.65]. While non-violent direct action had proved successful in Birmingham, some looked to the greater and more immediate impact that violence seemed to have. The "Burn, baby, burn" cry used in later race riots in Watts (Los Angeles), Detroit, and other American cities showed that "The 'rules of the game' in race relations were permanently changed after Birmingham."

![Project description [Word]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008043425_1-3e4ed50c123e3e03f00b9fc84ce61bee-300x300.png)