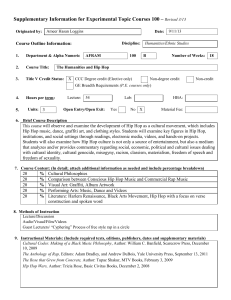

Hip Hop From Subculture to Popculture An Analysis of the

advertisement