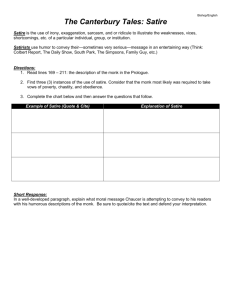

Press Kit

advertisement