Multigenre Inquiry Project.doc - English378InquiryProjects

Making Poetry Relevant:

Teaching the Basics Through a “Modern” Lens

Alyssa Topham

December 6, 2010

Dr. Sirpa Grierson

ENGL 378- Fall 2010

“The figure a poem makes. It begins in delight and ends in wisdom. The figure is the same as for love. No one can really hold that the ecstasy should be static and stand still in one place. It begins in delight, it inclines to the impulse, it assumes direction with the first line laid down, it runs a course of lucky events, and ends in a clarification of lifenot necessarily a great clarification, such as sects and cults are founded on, but in a momentary stay against confusion. It has denouement. It has an outcome that though unforeseen was predestined from the first image of the original mood-and indeed from the very mood. It is but a trick poem and no poem at all if the best of it was thought of first and saved for the last.”

– The Figure a Poem Makes, Robert Frost

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 0

Table Of Contents:

Preface:

Essay:

Genre 1: Newspaper Article

Genre 2: Art = Poetry!

Genre 3: Poetry/Classical Examples

Genre 4: Interview

Genre 5: Survey

Genre 6: Short Essay

Genre 7 : Music

Genre 8 : Movie Clip

Genre 9 : Intimate Observer Response

Genre 10 : Recipe

Epilogue :

Rationale :

Annotated Bibliography :

Works Cited:

Topham, BYU, 2010

23-26

27-30

31

32-33

34

35

2

3-11

12-14

15-17

18-19

20-21

22

36

37-38

39

Page 1

Preface:

I know that poetry is something that must be taught in an English classroom; it is always part of the curriculum map. However, while the necessary elements of poems are important, the idea behind poetry—what it is, what it does, and who it affects—are questions that often get pushed to the back of the line. As a future secondary teacher studying English Teaching at

Brigham Young University I think students should not only understand elements of poetry, but be able to find it in their lives and be able to relate to it.

Concepts should be taught so they can be relatable to students.

This project looks into teaching poetry through a lens of relevancy. I want my students to make use of the terms and parts of a poem I teach them, not simply understand the definition. I want to give them skills that they will use later to analyze poetry when they come across it. There are also new “modern” mediums in which poetry is situated, such as art and song lyrics, that can illustrate to students that the ideals of poetry surround them in their lives. My goal is to find topics that interest them, and the best way to teach them. That goal in itself “modernizes” the task of teaching poetry.

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 2

Essay: Teaching What Needs to be Taught in a Relevant Way

When I ask fifteen year old Parker about how he feels about poetry, he snaps his head up and with a look of disgust says, “I hate it.” When I ask why he sighs and explains, “Because the teacher makes it so boring! I don’t care about what some guy said two hundred years ago. She tells me it’s brilliant and should apply to me; I say, why the heck would it?” His answer made me question: How can a teacher make poetry more relevant to students? And what modern genres can be used to facilitate learning? As future secondary education teachers we know that we will be required to teach poetry in some form throughout the year to meet state core requirements. But, in order to make this an experience more enjoyable than pulling teeth, for both the teacher and the students, we need to address Parker’s concern. If we want students to understand and appreciate poetry we need to teach it in such a way that makes poetry relevant to their lives. Whether it’s by explaining the genre as a continuing art form, or using modern poems to introduce elements of poetry before tackling the “classics,” we need to be open to our students, care about what subjects/themes they would like to learn more about, and find methods to teach it in an engaging way.

Opening students’ eyes to the poetry that surrounds them in their

“normal” lives starts with teachers explaining the basics of the genre so they can identify it. As always, we need to be sure that we teach the content and

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 3

then apply that knowledge and learning to experiences and activities that will make students remember the main concept: that poetry is relevant.

The Basics: Defining “Poetry” and the Elements that Help us Analyze It.

When we ask our students on the first day of the unit to describe what they think poetry is, we’ll probably get a handful of answers. Some students may respond as Robert Frost did when he was asked was poetry was: “Poetry is the kind of thing poets write” (Kennedy 656). Poetry dodges a simple definition.

Kennedy and Gioia explain in their book “Literature: An Introduction to Fiction,

Poetry, Drama, and Writing” that poetry can be defined as: “a rhythmical composition of words expressing an attitude, designed to surprise and delight, and to arouse an emotional response” (656). With that broad definition firmly in place, which is fitting since we all have different opinions and definitions of poetry ourselves, our next task to the break down elements that make poetry a genre all its own.

Kennedy and Gioia break down their poetry unit into literary elements that help us analyze what the author is trying to say. The standard list includes (in no particular order): tone (poet vs. speaker), irony, words

(connotation/denotation), imagery, figures of speech (metaphor/simile/ personification, etc.), sound, rhythm, form (closed, open, different sonnets, etc.), and symbols. Well, we shouldn’t be surprised by anything that is included in this list. Wasn’t it what we were all taught? But we need to not only focus on these different subject areas. We need to explain and model that the concepts

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 4

are part of the bigger picture of “reading” a poem. One of Parker’s problems was that he didn’t know what the teacher was asking for when she asked him to

“read” a poem. If his teacher would have explained to Parker that he wasn’t expected to read the words of poem through once and magically understand everything just because he identified basic concepts such as imagery or figures of speech, I think he would have not been so scared of it. Here are some ideas for examining “facts” of a poem before jumping into the abstract:

Look at the poem’s title—any guesses to what it may be about?

Read the poem straight through without stopping—you can hear how it sounds, how it works, and what the subject may be.

Start with what you know

Look for patterns (symbols, types of literary devices, imagery, etc.)

Identify the narrator—this is most likely NOT the poet

Find the crucial moments—find the but or the yet that clue us into the poem taking a new direction

Consider the form—why this form? What does it do?

With these “concrete” ideas to look to, students can get the gist of the poem and be confident they know what the poem is about—one of the hardest things to get students to see because they are intimidate by the “deeper meaning.”

These basic concepts and techniques are handy tools to understand the basic skeleton of a poem; but where is the heart? In a sense, where is the relevance? We so often want our students to answer the “so what?” question, now it’s time for us to answer it as well.

The Heart of Poetry

The heart of a poem comes in the personal understanding of its function.

We teach students poetry because it is on the agenda yes, but we also teach it

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 5

to have students discover something about themselves. That is the answer to the “so what?” question. But this cannot happen if students feel that they can’t connect to the ideas presented in the “standard” poems we teach. “Often, the poetry we study in school is the language of others who may or may not relate directly to the students’ cultural lives, passions, and struggles. …They

(students) sometimes consider Poetry incomprehensible jargon that uses devices of years past with themes removed from contemporary society” (Perry

110). So what can we do about this?

The Power of Understanding: Writing and Subject Application

Numerous articles have been written about the power that comes from having students write poetry in conjunction with analyzing it. All of the vocabulary terms make more sense because students are dealing with it on a concrete level: they are making it relevant to their lives by applying it to their class work. “So often…we first introduce poetry…and ask students to analyze the text. After explicating the poem’s meaning to its smallest dimensions we then examine the form” (Perry 110). This typical procedure is understandable seeing that the NCTE Standards call for “Students [to] read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions of human experience” (Standards for the English Language

Arts 21). We want students to be exposed to the best poems and have an understanding of what they mean. But, we will have a hard time getting

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 6

poetry’s language and form to “mean” anything to students if we don’t make them active participants.

Students may be intimidated by the form of the great poets we read in class and feel that they can’t write something that “hard,” so they ignore the poem’s style, language, scansion, or form. But we as teachers “…believe that rich literature should be shared and discussed with students. We want students to know quality work, to breathe lyrical words, to embrace the power of poetic language” (Perry 110). So, we bring models into the classroom and write alongside them. We teach them lessons about specific aspects of poetry, taking time to explore and explain specifically so students have different literary tools to draw from. “Students will not develop a repertoire of writing skills and forms unless we teach them” (Perry 111, emphasis added). We let them choose their own topics/themes so they feel ownership of their piece.

Perhaps the pieces of poetry that will be more relevant to students’ lives are those that they write themselves. “Pushing students to leave the coziness of the known to try the unknown is one of the benefits of teaching. …[T]eachers can use poetry as a way to stretch students’ thinking” about themselves and the world around them (Perry 112).

Along with making poetry relevant by having students write it, we can look for opportunities to connect it to other activities or subjects they participate in during school. Music, dance, and art are all avenues to connecting poetry to something more tangible and relevant to students’ lives

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 7

because all of these categories are art forms. Music is a wonderful path to explaining the intricacies of the scansion, beat, and rhythm of a poem. Art is a fluid medium in which the observer draws meaning just like in poetry. Dancing is about movement, tempo, ebb and flow. Department collaboration in a school between the Art and English departments could maximize the time we have in class to discover poetry, and lead to meaningful experiences that confirm to students that poetry is found all around them. It is relevant.

While Parker may not be a dancer or play the piano he does love listening to his iPod. Perhaps that’s the avenue to him. Maybe in the past he hasn’t appreciated the “brilliance” of Wordsworth, but when asked to go outside and write about nature using the same rhetorical devices Wordsworth used, he begins to understand how smart the guy really was.

Teacher Reality: Duty (Always) Calls

Now some teachers may look at this way of teaching poetry as too ideal— there are not always going to be poems or activities that touch every single one of our students. And they are right. Some teachers get bogged down by the necessary aspects of poetry that are harder to teach than others that most students have not liked in the past. Some particularly addressed by scholars include scansion and the issue of assessing student poetry.

I can imagine that one of the most daunting tasks to a student is to figure out what the elements of the scansion are in a poem, and how they add

“meaning.” It was for me. In high school I was given a list of vocabulary terms

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 8

and told to define them using my literary book. “Trochee,” “anapest,” and

“spondee” sounded more like diseases than categories of scansion. Although I had the definition in front of me there was no follow up activities or further explanation that my teacher gave. I realize that my teacher probably didn’t do any because she didn’t know how to make it make sense to us. Barbara Mather

Cobb explains in her article: “Playing with Poetry Rhythm: Taking the

Intimidation out of Scansion,” that there are two possible reasons why students are scared of scansion: “(a) students have never practiced scansion or

(b) students have developed an aversion to it based on previous experience”

(56). Some teachers may feel that if students listen to music all day, which they do, they should be able to understand scansion. But there is much more to scansion than simply musicality. Cobb explains:

Those who have never worked with rhythm and meter are uneasy approaching the sounds of poetry. This discomfort may come, in part, from the decline in reading aloud in school or at home. Students think of music as rhythmic, but poetry, presented to them as text on a page, may not strike them as rhythmic, and they may not see the importance of a poem’s rhythm to their reading of that poem. (56)

Not only do we need to give them definitions but we need to involve them in discovering them. We need to read out loud and have them read out loud. We need to break down parts of poems, identify the different forms and beat them out together. Teachers may assign strong beats as claps and unstressed as snaps and have the entire class sound out the rhythm together.

While some may ask how we make this specific aspect “relevant,” we must remember that being able to teach students skills gives them a toolkit of

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 9

strategies to use; skills are relevant. Anything a student feels he or she can use

they will see as relevant.

Now a small note about assessing poetry. Doing poetry units we should have our students write poetry as well as interpreting it. We all may ask: “How can a teacher grade student poetry while making is clear that the writing, not the poem’s emotion or subject, is the target of that grading” (Griswold 70)?

Students will come to understand through analyzing poetry that it is an art form riddled with personal emotions, and may divulge some of their own while writing. This “…makes it difficult for students to receive feedback and grades

[because]…students would interpret suggestions for improvement or, worse, low grades as negative feedback about not just their poetry but also themselves” (Griswold 70). We need to be specific on our expectations for the poetry our students write and supply them with a detailed rubric beforehand.

These specifics should not limit student choice but give them proper guidelines. Andrea Griswold in her article “Assessment Lists: One Solution for

Evaluating Student Poetry” uses “assessment lists” to assess students’ poetry.

Here is an example of such a list:

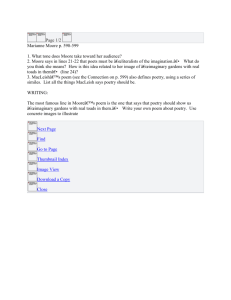

FIGURE 1. Assessment List

Effectiveness

My poem . . .

1. Has a compelling title

2. Has at least twenty lines

3. Draws the reader in from the beginning

4. Has three original similes that reinforce the meaning

Points Self-Evaluation

5

10

6

12

5. Has three instances of sensory language that reinforce the meaning of the poem

6. Uses space (formatting) to strengthen the meaning

7. Conveys a meaning or purpose (list here):

12

10

10

Total 65

Topham, BYU, 2010

Evaluation

Page 10

Process

For this poem, I . . .

1. Had at least three peer conferences and one teacher conference 12

2. Made meaningful revisions/experiments after each conference

(attach conference sheet) 12

3. Attached all drafts of the poem to the back of the final draft 11

Total 35

(Griswold 72)

There must be a balance between what a student wants to expresses and elements we want them to apply. Using assessment tools such as this list gives students both freedom and boundaries.

Conclusion:

Our goal should be to give students a positive experience with poetry.

While there are state core requirements and standards that must be met we do not have to teach it as it has always been taught. We can get students’ to understand and appreciate poetry through open, engaging lesson plans that cause students to become more comfortable with the genre. With that comfort comes more opportunities to not only discuss the elements of a poem by the meaning: the meaning for them individually. Students can write poetry to learn not only important aspects of scansion and rhyme, but about themselves. An involved teacher that cares about his or her students will take the time to find poems that students will connect to, and create assignments that make them feel as if they have something to contribute to the world-wide dialogue of poetry. “Poetry is a powerful teaching tool. Let’s not be guilty of dissecting it so that there is nothing left but the poem’s skeleton” (Terry 113). If we look straight into the heart we’ll find a way to connect to our students.

Topham, BYU, 2010 Page 11

JUST THE FACTS

The hard hitting truth about what goes on behind those closed doors…

December 2010 Edition: Volume 3

Editor and Writer: Agent Alyssa Topham –“I can make poetry RELEVANT by explaining to my students, and knowing for myself, why I think poetry is taught. “

Answering the Tough Questions about Poetry:

High school and middle school students and teachers are at a constant struggle in the classroom over poetry. In fact, the brawl that occurred in Ms.

Sweeny’s 7 th grade classroom this week called for a strict investigation. The culprit, Andy

Butler, just fresh off of elementary school explained that the “incident” was due to the fact that this poetry was “new,” and it was “hard.” “She wanted to me analyze it!!” Andy screamed as they took him to the principal’s office.

Andy knew about couplets and haikus. He even had a Shel

Silverstein book! Why was he being forced to learn this?

Well, I decided to get to the bottom of this, for little Andy and hundreds of kids out there in this school just like him.

Let’s delve into this “new” poetry—poetry that might not even rhyme.

What is it For?

Poetry is here for beauty, right? The fact that human

Topham, BYU, 2010 beings long for passion and all that stuff, that’s why it’s here. Well folks, from deep investigation I found that:

“Poetry is an inclusive art, demanding all of the senses, for composition, understanding, teaching, and appreciation”

(Kryder 34). Poetry is here to not only sound pretty, but to take out thinking to a deeper level. It makes our minds bend around the “facts” we’ve been taught and grasp tightly around the idea of interpretation.

Now, teachers understand this, don’t they? They know that poetry requires a different mindset and that they should prepare their students for that.

And if they want students to grasp onto the new skill set that poetry requires, teachers

“know that [they] must make the leap out of seemingly inviolable daily schedules, omnipresent test-taking modes of assessment, and the competitive approach to learning to discover what [they] can with students” (Kryder 35, emphasis added). Poetry is for

Page 12

students to discover something about themselves.

What does it Do?

Well to put it bluntly, poetry, more often than not, makes our heads hurt. Trying to decide who the speaker is, what is he saying, and what he actually means takes a lot of work. But, when all that is said and done,

“poetry welcomes opportunities for discovery beyond the page”

(Kryder 34). Poetry lets students go a little crazy.

After all, each student brings his or her own life experiences and beliefs to the table, which influences the lens which they see through.

With the acknowledgement of this fact, poetry also is hard work for the teacher. “Poetry, like all the arts, is experiential, and as such bids [teachers] to join together with … learners at all times” (Kryder 35). Poetry binds teachers and students through the process of putting pieces together—everyone is a learner.

Why is it Important?

Poetry is important because it makes us connect to the world around us—our world. Each of us has our own personal likes, hobbies, dreams, and goals. Each of us is going through things: happy things, bad things, things we want to forget. We are all individuals. Poetry is important because it speaks to you and me as individuals.

I suppose we can ask the question: “Why is poetry a core

Topham, BYU, 2010 requirement that we HAVE to study?” It’s because it will help students. Although they may be skeptical at first, there will be an “ah ha!” moment.

Something will touch them in some way when they least expect it. That’s what teachers are selling to students, and someday they’ll discover they were right.

Closing Thoughts

Although it’s hard work, poetry is worth it. Poor little Andy didn’t quite get the big picture. Perhaps his teacher didn’t explain these basic standards to him. But as teachers and students work together to understand what poetry is to every single one of them, they will benefit from a positive learning environment, and learn together. At least, that’s what I’m hoping for.

Page 13

APPLICATION:

Using this newspaper article as a model, write your own column about experiences you have had with poetry. What are some of your favorites? Do you have a favorite poet? You have the opportunity here to talk candidly—you’re stating facts.

Don’t say that you like it if you don’t. Be honest—with me, your classmates, and yourself.

REQUIREMENTS:

Article must be at least one column, single spaced, and contain one graphic. Your column should focus on why poetry does/does not matter to you. DUE ________________

POETRY = ART!

I can make poetry RELEVANT by showing that analyzing poetry is like analyzing art—what draws your eye and heart, and your interpretation of those things, shows what speaks to you. Discovering poetry is an individual process.

Instructions: Think about the last time you went to a museum. Looking at all those paintings there were some that you liked, and some that you didn’t. WHY? Especially when looking at “modern” art, how can you explain why you consider something “good”? When you were making these observations and judgments about these paintings you were ANALYZING them. You do the same thing when you analyze or dissect a poem.

Look at these different modern paintings and write what you see. Now, what do you think the author was trying to convey through that? Were they successful? Why or why not? Do you like the painting? What do YOU think it is trying to say? Use the graphic organizer given to you to map out your ideas—find where things connect, and where they differ.

Christeas, “Hydra 12”

1

Van Gough, “The Starry Night”

“Dream Away”

2

Poetry and Art Combine!

3

I can make poetry RELEVANT by making students appreciate the difficulties of writing poetry by having them do it themselves. By writing they understand more of what goes into a poem, and how it is at times a struggle to make it relevant to others.

Mimicking Classical Examples (Sonnet writing)

Assignment : We have been talking in class about the different parts of sonnets, and how different

“types” of sonnets differ from each other. We’ve also just completed analyzing both Shakespearean and Patrarchan sonnets regarding their rhyme scheme. In order to understand the complexities of writing poetry, and how meter and scansion add to the tone/feel of a piece, write your own soliloquy in the

Shakespearean style. Pick a character from a novel and a situation they find themselves in. Write a brief summary at the top describing the situation and what you are striving to explain. Don’t forget iambi c pentameter!!!

Here is my own example.

Soliloquy: Written by Alyssa Topham

Inspired by Jane Austen’s classic, Persuasion , from the point of view of Anne. The main characters and lovers Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth have been parted for eight and a half years because Anne was persuaded to not accept his offer of marriage. Now reunited, the two have been thrown together again and are trying to hide their feelings form each other. The Captain can no longer bear it and writes a letter to Anne explaining that he has loved no one by her, and pleads that that he is not too late to earn her love back. This is her reaction to the letter.

Oh, help! For years I’ve dreamt of hearing words

As soft as these. Two hearts, that once would beat

As one, would be allowed to speak out loud

Once more. We’re town apart by oceans deep

Of phantoms drenched with days and nights of past.

Such nights and days so sweet they cause me ache.

I craved the waves of time would drown the hurt;

And wishing seas of space between us would

But remedy the injury within.

My heart and head a battle fought. Alas,

Ther’s ne’er a living thought, or beat of breast

That can’t but say, “My Own! My Love! Captain!”

Yes mem’ry brought me pain. But anguish sought,

To know what a fate bestows again to me.

4

At last would I now wake to find this true?

I thought that pride would change his soul to ice;

Forget what warmth there was, and is! My hopes,

Like water dashed ‘gainst rocks, now mend. The heav’ns

In time now open way for remembrance

To mend our battered souls. My tears are dry.

The argument of old, which gender loves

Strongest, deepest, longest…I leave to you.

Both love as strong, and deep, and long, as their

Dear heart can hold. Oh, I can’t breathe! Pray God

To give my feet they speed! I pray I’m not

Too late to claim what ought to be my own.

5

Veteran AP Literature teacher at Alta High School Talks about Poetry in Her Classroom

The Five Questions We’ve All Been Talking About

Interview Conducted By: Alyssa Topham

“I can make poetry RELEVANT by taking advice from veteran teachers, and building upon what I know works.”

Sitting in Mrs. Clark’s decorated classroom where she teaches three periods of AP

Literature, as well as a Journalism course and two periods of 12 th grade Language Arts,

I don’t have to wonder if this woman is a good teacher. The walls are covered with quotes from novels, student papers, and books fill the walls. I sat down with Mrs. Clark and was able to get her insights into the realities of teaching literature to all types of students.

1.

Is getting students to understand poetry difficult? How so?

Yes…they come to it with a preconceived notion that it will be difficult; they don’t tend to have the experience and thus the comfort with verse as they do with prose, and they lack the patience to analyze it. However, after instruction and guidance and some fun, contemporary poems thrown in for good measure, most students warm up to poetry.

2.

In your opinion, what are the “classic” poems that every student should read?

6

They should have exposure to classic poets…which poems you choose is usually a matter of teacher preference; I always include

Shakespeare, Dickinson, Frost, Whitman, Donne, Wordsworth, and Plath. I also use Billy Collins quite a bit-he’s so accessible and clever. I use the Perrine Sound and Sense book in AP, and it’s a marvelous text with a variety of classic poets from the 17 th century onward.

3.

What are some of the ways you make poetry exciting for your students?

I guess my love and enthusiasm carries the poetry unit the most; I am also selective about the poems we discuss, mixing old with new. I also spend a lot of time discussing the poems so the students can have moments of enlightenment and therefore feel excited about the poems rather than daunted by them.

4.

From your experience, are there certain “types” of students that like poetry and some that just don’t? Who are they?

Hmmm…I guess the “types” are AP students, although they are not all fans in the beginning. I think if you show that poetry shows up everywhere, such as song lyrics and advertising, those students can begin to like it.

7

5.

What are some activities you have done with your students that have made them see the relevance of poetry in their lives?

I present poetry in a larger context of language arts so it’s not necessarily isolated. In other words, the same literary terms studied with prose, such as character, setting, theme, tone, imagery and figurative language, are not only part of the poetic genre but also part of the pursuit of knowledge in the overall language arts category. I also have them write some poems of their own with plenty of examples to model. We submit their best to the school lit magazine for publication as well.

8

Students Explain Their Thoughts About Poetry—

Unedited.

Compiled By: Alyssa Topham.

“I can make poetry RELEVANT by asking students what they are interested in, what has worked in the past, and what hasn’t.”

Background Information: 8 high school students surveyed from 3 different high schools around the Canyons School District in Sandy, Utah.

50% of students like studying poetry in class.

When asked what the first word that came to their mind when they hear the word “poetry,” answers included (in no particular order):

1.

Love

2.

Art

3.

Nature

4.

Boredom

5.

Yellow woods

6.

Sleep

65% of students said that how well poetry is taught by their teachers makes them like it/appreciate it more.

When students were asked what topics they wanted to study through poetry, answers included:

Love

Sports

Things that are different or strange

Twisted reality

Something that challenges my mind

It makes you think in a new perspective

Humor

Darkness

Sadness

Heartbreaks

75% of students said they would like poetry more if they felt it applied to their lives.

Short Essay: Exploring the Idea of the “Modern” Poetry Unit

9

I can make poetry RELEVANT by learning from my students about what they want to learn, and exposing them to things they may never have thought of; opening their minds is the key.

When I hear the word “modern,” my mind immediately jumps to strange architecture in houses that I would never use, strange contorted metal statues that I’m sure have no meaning, and paintings by

Jackson Pollock. They all seem so far-fetched; they mean nothing because they mean everything. But perhaps, this is

“…there is a fluidity to the definition of a ‘modern’ poem because any poem that students can connect to is

“‘modern.’” what is wonderful about “modern” ideas. Most often than not, teachers shy away from the “modern” simply because it is not “classic.” As I write this I ask myself, “Why am I putting these quotes around these words? What defines what is modern and what is classic?”

Poetry in the classroom has been a long standing tradition. We all know what we should teach, and what students should get from the pre-selected bunch: an appreciation of the work that goes into making a poem great, and who the great poets are. I am not one to argue that John Donne wasn’t brilliant, or Byron wasn’t genius, but I know that as a high school student myself, when I looked at the title, “Holy Sonnet XIV: Batter My Heart, Three-personed God,” I rolled my eyes and got prepared for another boring lesson. The classics are important but I think that if we as teachers pair “classic” poems with more “modern” poems students can be exposed to the main theme or idea of the poem multiple ways, so if they don’t get it through one, they have a chance with another.

What is more important than the specific poem we teach are the topics which we choose to expose students too. I believe that although there are “modern” poets, meaning that they write within the last century, there is a fluidity to the definition of a “modern” poem because any poem that students can

connect to is “modern.”

10

“A modern poetry unit would mainly focus on subjects that occur in students’ lives: heartbreak, success, sports, activities, friendship, family relationships, etc.”

My idea of a modern poetry unit would be combining more recent poets with older poets and show the similarities and differences between their outlooks on specific topics, symbols, themes, etc. Students would come to realize that the same topics are being spoken about, just in different ways. A modern poetry unit has students writing poetry themselves so they can jump into the mind of the poet, and get a glimpse at the difficulties of writing a proper poem. A modern poetry unit would mainly focus on subjects that occur in students’ lives: heartbreak, success, sports, activities, friendship, family relationships, etc. As teachers we have to judge the value in every piece of literature or prose we teach. What will students gain? John Pfordresher claimed in the English Journal that teachers should look for “texts that explore emotion, intuition, mystery, and…the transcendent” (27). We need to look for poems that will

“explore [the students] realms of human experience” (Pfordresher 27).

I may pick up a poem that no other teacher is focusing on. It may be about a topic that other teachers shy away from. But as long as my students come away learning not only about the form, scansion, and rhyme scheme, but about themselves as individuals, than the poem, regardless of what it is, has done its job. I have weighed the value of the piece, and have come out with a knowledge of the results I want. Isn’t that what poetry is supposed to do?

In the English Journal in 2006 teacher Tamara Van Wyhe realized the impact that poetry, not specific poems, had on her classroom and student. Her own love of the genre of poetry was passed on to her students and embedded itself into other instruction as she used it as avenues into other texts. She realized that if she wanted to impress upon her students the importance of poetry, it was

“critical that [she] create[d] memorable opportunities for students to learn lasting lessons” (16). We

11

as teachers desire our students to go away from our class remembering… something! Something that will help them in their lives. Van Wye asserts: “Poetry is helping them to do this; I know, because they tell me through their writing in and out of class…. What my students will remember, I hope, is that words on a page have meaning only when a reader or writer makes the words his or her own” (16). When students can construct meaning from words they become an active participant in the poem, discovering and divulging the wordplay. “Wordplay is the resonance poets create by exploring the possibility of words…as those words collect, collide, and constrict, then converge, and, ultimately, connect” (Figgings et. all 29). Notice that Van Wye doesn’t specify which poems they were that they studied. She instead says that it is the idea of the language of poetry and the tools to understand it that influences students. Through discovering poetry on their own, through their own lenses, which makes it “modern,” Van Wyhe’s students became “poets, lovers of language, and wordsmiths” (16).

That is “modern” poetry. Although some may argue that Frost and Hughes while

“contemporary” are not “modern” because of the time period they wrote in, when all is said and done it doesn’t matter. Can students connect to these poems? Yes. Is there something they can learn from them? Yes. Then, they are modern. So we can all wipe the sweat from our brow because we don’t have to go looking for a whole handful of poems written within the last twenty years just so we have a “modern” poetry unit. We can take classics and make them modern. Though engaging lessons and personal assignments we can open students’ eyes to the possibility of poetry. We teachers may echo John Milton who so beautifully wrote:

“When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent”

12

Although this was written in the 17 th century can this connect to our lives? Yes. Then, we have discovered a modern poem!

Idea List of Poems Probably Not In the High School Textbook:

Forgetfulness: Billy Collins

Tongue-Tied: Ingrid de Kok

Dulce et Decorum Est: Wilfred Owen

Jabberwocky: Lewis Carroll

Final Love Note: Clare Rossini

The Runner: Walt Whitman

Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day?: Howard Moss

A Martian Sends a Postcard Home: Craig Raine

Money: Dana Gioia

Shakespearean Sonnet: R.S. Gwynn

Swan and Shadow: John Hollander

Snow White: Andrea Hollander Budy

Cinderella: Anne Sexton

Deliberate: Amy Uyematsu

Poetry: Marianne Moore

The One Girl at the Boys’ Party: Sharon Olds

Running on Empty: Robert Phillips

13

Sweet Poetry of Music:

I can make poetry RELEVANT by bringing in models and examples from music my students are listening too. Discovering that different types of poetry are being used even today illustrates that poetry is a CONTINUING art form; thus it’s always relevant.

Music is powerful. We all listen to it. We all have our favorite songs and know all the lyrics. We pick up on beats and know what “type” of song it is going to be: R&B, country, punk rock, rap, etc. Well, we all know that music is a type of poetry because words rhyme at the ends, right. Well, what about words that almost rhyme, or songs that don’t rhyme at all? They are still music aren’t’ they? Let’s look at these examples where musicians “broke” the rules, or modified them. Because they did this, how did it affect the music? What about the “beat” or scansion of the piece?

Run D.M.C. [J. Simmons/D. McDaniels] -1986 from

“Peter Piper”

Now Dr. Seuss and Mother Goose both did their thing

But Jam Master's gettin loose and D.M.C.'s the king

‘Cuz he's the adult entertainer, child educator

14

Jam Master Jay king of the cross-fader

He's the better of the best, best believe he's the baddest

Perfect timin when I'm climbin I'm a rhymin acrobatist

Lot of guts, when he cuts girls move their butts

His name is Jay, hear the play, he must be nuts

And on the mix real quick, and I'd like to say

He's not Flash but he's fast and his name is Jay

It goes a one, two, three and…

Jay's like King Midas, as I was told,

Everything that he touched turned to gold

He's the greatest of the great get it straight he's great

Playing fame ‘cuz his name is known in every state

His name is Jay to see him play will make you say

God damn that DJ made my day

Like the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker

He's a maker, a breaker, and a title taker

Like the little old lady who lived in a shoe

If cuts were kids he would be through

Not lyin y'all he's the best I know

And if I lie my nose will grow

Like a little wooden boy named Pinocchio

And you all know how the story go

Trix are for kids he plays much gigs

He's a big bad wolf and you're the 3 pigs

He's a big bad wolf in your neighborhood

Not bad meaning bad but bad meaning good…There it is!

15

We're Run-D.M.C. got a beef to settle

D's not Hansel he's not Gretel

Jay's a winner, not a beginner

His pockets get fat others’ get thinner

Jump on Jay like cows jumped moon

People chase Jay like dish and spoon

And like all fairy tales end

You'll see Jay again my friend, hough!

Lennon/McCartney- “Eleanor Rigby”

Ah, look at all the lonely people!

Ah, look at all the lonely people!

Eleanor Rigby

Picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been,

Lives in a dream,

Waits at the window

Wearing the face that she keeps in a jar by the door.

Who is it for?

All the lonely people,

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people,

Where do they all belong?

Father McKenzie,

16

Writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear,

No one comes near

Look at him working,

Darning his socks in the night when there's nobody there.

What does he care?

All the lonely people,

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people,

Where do they all belong?

Eleanor Rigby

Died in the church and was buried along with her name

Nobody came.

Father McKenzie,

Wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave,

No one was saved.

All the lonely people,

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people,

Where do they all belong?

Ah, look at all the lonely people!

Ah, look at all the lonely people!

17

Seeing is Believing:

Dead Poets Society, 1989, Directed by Peter Weir

I can make poetry RELEVANT by inviting students to ask themselves, “What will my verse be?”

Show movie clip where Professor John Keating begins his poetry unit, and surprises all his students by explaining what the purpose of poetry is to them as individuals.

Obtaining the Movie: rent it from the school library or just watch the main scene on the internet via http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tmayC2AdkNw&feature=related

Application: Give students the quote found below and the continuing assignment throughout the unit.

Assignment: From this clip we see that poetry is a part of human experience—YOUR human experience. Although you may not find this particular Whitman poem pulling at your soul, there are poems out there that will. Throughout this unit you will be asked to find poems that move you. You won’t need to explain them to the class or the teacher…just yourself. Use this page to record at least 10 poems that you find that you like. At the end of the unit you may use these poems to help inspire your own writing. Also, the end of unit exam will ask you to analyze a poem. You may pick the poem from your list so it is a poem that you care about.

Get searching!

“We don't read and write poetry because it's cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for. To quote from Whitman, ‘O me! O life!... of the questions of these recurring; of the endless trains of the faithless... of cities filled with the foolish; what good amid these, O me, O life? Answer. That you are here - that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse.’ That the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?”

18

Intimate Observer

Response Featuring:

The Mending Wall

(Made famous by Robert Frost)

Compiled by Alyssa Topham

“I can make poetry RELEVANT by presenting poems that are potentially meaningful for students.”

****Manuscript rediscovered; parts have been reconstructed and are not guaranteed to be completely accurate.****

“I can see why everybody thinks that I’m necessary. After all, good fences make good neighbors don’t they? That’s what he thought too when he wrote about me, or so I supposed.

19

The speaker in the poem ends up arguing that walls and fences are old fashioned ideas. But then again, everyone has things they either wall up inside themselves or try to fence out because I reckon they don’t want to deal with them. That’s most likely what I’m here for— that’s what I symbolize. After all, I wasn’t built in a day. The stones were chosen very carefully before they were stacked on top of one another.

Everything had to be just right if I was going to do my job well. That’s what Frost was doing when we wrote about me: picked just the right words and layered them just right so they could mean something more. He was a master craftsman to build me so everything fit just right.

20

“He also knew that I would be the perfect subject and symbol for this poem because I’ve been around the block if you know what I mean.

I’m old—I’ve seen plenty of neighbors and people hurt each other. I’ve seen brother turn against brother during wars and such. Different parts of me have been taken down over time, but only to be built up again. Frost discovered that himself; he saw that no matter how many stones fell, they were always picked up again.

That’s what he wanted me to tell people. He was a smart one, that feller.

“I suppose that’s what he meant by all his writings. I mean, yellow woods, fire and ice, and stone walls aren’t things that you all experience

21

in your life, but they could mean something else. Something deeper, I reckon. Frost always was looking for ordinary things to talk about unordinary emotions, questions especially.

’Cause in the ordinary, the reader can either decide to take it just as a compiling of pretty words, or break down their walls and find the gold mine.

“Sometimes I don’t even know what he was getting at but, I trust him. ’Cause if I know anything I know he wasn’t just writing for himself, he was writing for you.”

Classroom Application: In order for students to understand the different voices of poetry (the

22

poet and “speaker” isn’t the same thing) present this type of writing to show the varying perspectives a poet can express. Have students mimic this model by picking an object in a poem and write from that perspective.

This Just In…New Recipe!

From the Kitchen Of: Alyssa Topham

Notes: I can make poetry RELEVANT by following the recipe for a successful poetry unit.

Recipe For: A Successful Poetry Unit

2 cups of prepared teacher; organizes is best—some days shaken, but never stirred

23

3 heaping tablespoons of communication-students, teacher, and poet are free to express themselves

1 positive, safe, learning environment; warm @ room temperature; DO NOT melt!

Directions:

Stir the above ingredients together but not TOO fast or consistency will fall flat.

Add small teaspoons of RELATIVE poems one @ a time; allow to settle before adding

Bake @ 180 degrees for 4 weeks; cut into bite sized morsels and enjoy!!!!

Epilogue:

Through doing this project I have discovered that it is up to me as a teacher to make poetry accessible to my students. If I want my students to have confidence when approaching a poem and appreciate it for its beauty and craft, I need to show them myself why I love poetry. I need to bring in texts that have touched me and explain why. I need to share some poems I have written for myself, even if they are personal. I need to come up with creative activities

24

that will explain concepts in an applicable way. If I want my students to see poetry as a relevant force in their lives I need to help them discover it all around them.

Yes, we as teachers can make poetry relevant to our students’ lives. It will take more time and effort on our part, yes. But, the question we have to ask ourselves is, “Will it be worth it?” Just think back to Parker who had the notion that none of the poems he was asked to study had anything to do with him. Why? Because the teacher did not take time to explain how it could. They did not give him the opportunity to tangle with the meaning and words. They didn’t give him the chance to try to write his own poem using that pattern. He’s right. It wasn’t relevant.

The choice is mine as a teacher.

Rationale:

Newspaper Article: I choose to include this genre because newspapers are all about the facts. I decided that a good project starts with the facts and perceptions on poetry, including problems and issues.

Art: Because poetry is an art itself it would be difficult to talk about its movement and themes without bringing in art as a compare/contrast. Art gives an opportunity to talk about abstract concepts and feelings which is applicable to poetry.

Classical Examples: Including a poem is only fitting for a paper about poetry. Also, as it is a poem written by myself following a certain pattern of poetry (sonnets) it shows how poetry can be modeled and incorporated.

25

Interview: This genre was essential because it shows personal reactions from a teacher who is experienced about teaching poetry. It shows her own practices and reactions to questions I wanted to address.

Survey: I wanted to include this genre because I wanted to include students’ opinions about the topic. This was a good way to do it because it shows the facts and remains anonymous for the students.

Short Essay: This essay allowed me to explore one specific aspect of my topic: “modern” poetry. This helped me hone in on the purpose of that term in my paper without taking up space in the main essay.

This provides clarification.

Music: As poetry focuses on rhythm and flow, examining patterns in music would be extremely beneficial to students. Also, illustrating that poetry is found in music that they listen to every day would show students’ the relevancy of it.

Movie Clip: This clip from “The Dead Poets Society” shows a teacher explaining the relevance of poetry in the boys’ lives. Also, it creates a question (What will your verse be?) that could serve as the overarching question of the unit.

Intimate Observer Response: This genre allows a look into poetry from a different perspective. We can gain insight into a poet, their writing, or poetry itself from a different avenue that people may not have realized before.

Recipe: As a recipe gives the basics to make something delicious, I wanted to include one to show the necessary ingredients to make a poetry unit successful. All of the “ingredients” came from my research while doing this project.

Annotated Bibliography:

1.

Kryder, John. “Discovering the Inclusive Art of Poetry.” English Journal

96.1 (2006): 34-39. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

This article was very eye-opening to the influence that poetry can have outside of the Language Arts classroom. He personally was involved in a school wide collaboration between departments to make poetry more relevant and shares his experiences. From this article I got the idea for not just collaboration between English teachers, but with other school departments.

2.

Perry, Tonya. “Taking Time: Teaching Poetry from the Inside Out.”

English Journal 96.1 (2006): 110-114. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

26

This article focused mainly on the act of writing poetry alongside reading and analyzing. Perry does an amazing job of pointing out problems that students have with analyzing because teachers don’t ask them to write first; students always write after. Perry focuses on the skill of wordplay and how we can make words relevant for students.

3.

Figgins, Margo; Johnson, Jenny. “Wordplay: The Poem’s Second

Language.” English Journal 96.1 (2006): 29-35. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

This article was very insightful in the “modern” ways that teachers can break down the idea of language for students. As they become more comfortable with wordplay they will be able to construct their own meaning.

4.

Cobb, Barbara Mather. “Playing with Poetry’s Rhythm: Taking the

Intimidation Out of Scansion.” English Journal 96.1 (2006): 56-61. Web.

1 Oct. 2010.

Cobb’s article focused on the main problems students have with scansion. I was able to glean numerous ideas on how to teach certain forms in an environment of open communication. Explicit instruction and demonstration is the key. Cobb also answered questions I had about scansion.

5.

Van Wyhe, Tamara. “Remembering What is Important: The Power of

Poetry in my Classroom.” English Journal 96.1 (2006): 15-16. Web. 1 Oct.

2010.

This was a “testimonial” to the affect poetry can have in the classroom.

Van Wyhe used personal experiences that I thought extremely helpful in looking at what good teachers can do for students. The correct teacher attitude makes all the difference.

6.

Pfordresher, John. “Choosing What We Teach: Judging Value in

Literature.” English Journal 82.5 (1993): 27-29. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

This article was one of the first ones that I discovered that focused my argument around relevant poetry for students. I as a teacher need to judge the value of every poem that enters my classroom, and only give my students the best.

7.

“Standards for the English Language Arts.” NCTE, International Reading

Association. Chapter 2, page 11

These standards are the backbone of teaching. This supplied me with background knowledge about the specifics of poetry in the classroom, and served as evidence in my paper.

8.

Kennedy, X.J., Gioia, Dana. “Literature: An Introduction to Fiction,

Poetry, Drama, and Writing.” Pearson/Longman, New York. 2007. Print.

27

This book was a wonderful outline of what teachers’ books will look like.

It not only gave all the basic outline for the core ideas taught with poetry, but gave ideas of poems not traditionally read in the classroom.

Works Cited:

Cobb, Barbara Mather. “Playing with Poetry’s Rhythm: Taking the Intimidation

Out of Scansion.” English Journal 96.1 (2006): 56-61. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

Figgins, Margo; Johnson, Jenny. “Wordplay: The Poem’s Second Language.”

English Journal 96.1 (2006): 29-35. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

Kennedy, X.J., Gioia, Dana. “Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry,

Drama, and Writing.” Pearson/Longman, New York. 2007. Print

28

Kryder, John. “Discovering the Inclusive Art of Poetry.” English Journal 96.1

(2006): 34-39. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

Perry, Tonya. “Taking Time: Teaching Poetry from the Inside Out.” English

Journal 96.1 (2006): 110-114. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

Pfordresher, John. “Choosing What We Teach: Judging Value in Literature.”

English Journal 82.5 (1993): 27-29. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

“Standards for the English Language Arts.” NCTE, International Reading

Association. Chapter 2, page 11

Van Wyhe, Tamara. “Remembering What is Important: The Power of Poetry in my Classroom.” English Journal 96.1 (2006): 15-16. Web. 1 Oct. 2010.

29