Doplnky_skara_Brae

advertisement

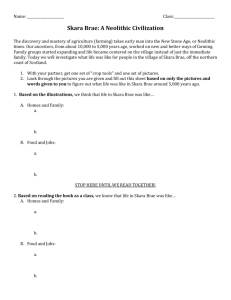

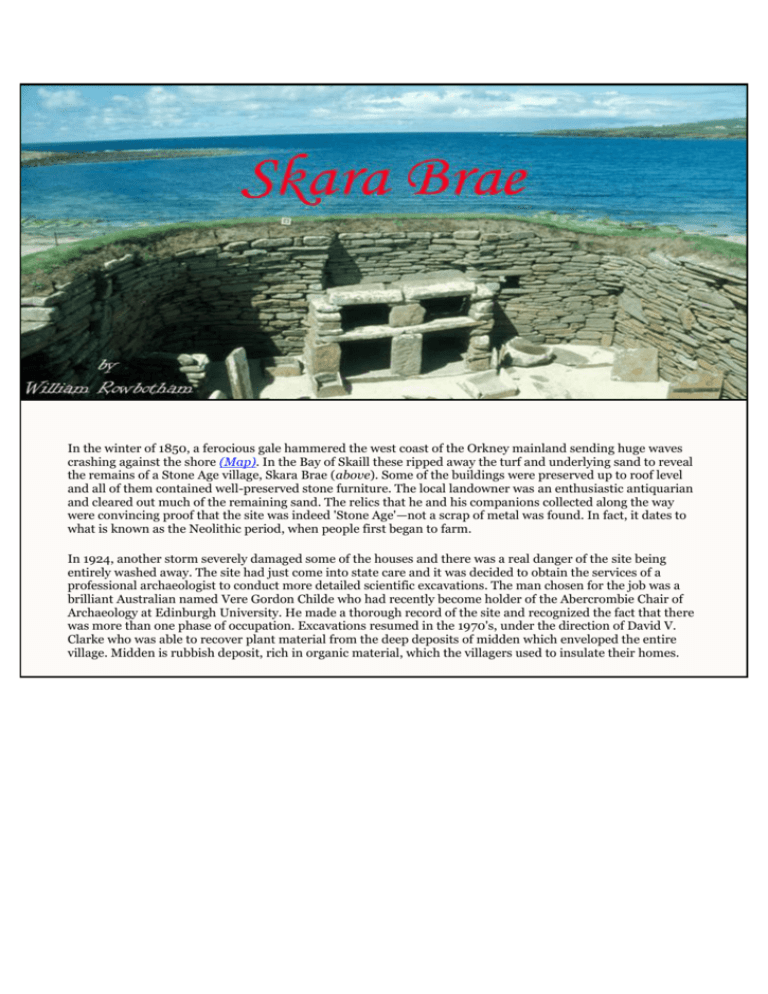

In the winter of 1850, a ferocious gale hammered the west coast of the Orkney mainland sending huge waves crashing against the shore (Map). In the Bay of Skaill these ripped away the turf and underlying sand to reveal the remains of a Stone Age village, Skara Brae (above). Some of the buildings were preserved up to roof level and all of them contained well-preserved stone furniture. The local landowner was an enthusiastic antiquarian and cleared out much of the remaining sand. The relics that he and his companions collected along the way were convincing proof that the site was indeed 'Stone Age'—not a scrap of metal was found. In fact, it dates to what is known as the Neolithic period, when people first began to farm. In 1924, another storm severely damaged some of the houses and there was a real danger of the site being entirely washed away. The site had just come into state care and it was decided to obtain the services of a professional archaeologist to conduct more detailed scientific excavations. The man chosen for the job was a brilliant Australian named Vere Gordon Childe who had recently become holder of the Abercrombie Chair of Archaeology at Edinburgh University. He made a thorough record of the site and recognized the fact that there was more than one phase of occupation. Excavations resumed in the 1970's, under the direction of David V. Clarke who was able to recover plant material from the deep deposits of midden which enveloped the entire village. Midden is rubbish deposit, rich in organic material, which the villagers used to insulate their homes. Skara Brae with Skaill House in the distance There were at least three principal phases of construction at Skara Brae (Figure 1), representing at least six centuries of occupation, from about 3100-2500 BC. As was the custom throughout, the earliest houses were built using midden material in the construction of their walls, implying the existence of an even earlier settlement. These walls consisted of an inner and an outer skin of dry stone with the space in between filled with the aforesaid midden material which served as insulation. In fact, the whole village was built hollows scooped out of a large heap of the stuff and it was packed up against the walls and on top of the roofs. The stone was the ubiquitous red sandstone found all over the islands. It tends to fracture into slabs which are just about the right thickness for the job. At its greatest extent the community consisted of seven or eight semi-subterranean huts built right up against one another and linked together by paved tunnels. The Bay of Skaill did not exist at the time and Skara Brae was located in the middle of low grassland which ran out over the dunes to the ancient shoreline, a few hundred metres away. After the site was abandoned, it was buried beneath the sand which preserved the houses up to the full height of their walls. No trace of the roofs survives. Wood has always been at a premium in Orkney but driftwood from the Carolinas or the ribs of beached whales would have provided a suitable framework to carry a covering of turf. The inhabitants raised livestock including cattle, sheep, goat and pig and grew crops of barley and wheat. Like their modern descendants they took advantage of the rich resources of the North Atlantic. Although no fishhooks have been found, huge quantities of fish bones (cod and saithe) along withlimpet shells were recovered. They used a type of pottery known as Grooved Ware, flat-bottomed jars and bowls with deeply incised decoration. Tools were made out of the local chert or sandstone and bone was used to make pins for fastening clothing and simple jewellery (Figure 2). The buildings were all single-roomed structures, oblong and ranging in size from about 20-35 square metres. All of the houses were linked together by a system of low tunnels, less than a metre high and half a metre wide. The short entrance passage was fitted with a door which could normally be barred from the inside, froma small cell just inside the door where the sliding bar was housed. They normally had small cells built into the walls, some of which were used for storage but there were a few with drains leading to the outside which Childe believed to be lavatories (Figure 3). The drains from the individual huts emptied into a sewer system which connected the entire village. Reconstruction of house interior (drawing by Stuart Piggott) The typical house—in the final phase, at any rate—had a rectangular kerbed hearth in the centre of the room (see above). The hearth was clearly the focus of family lifeOn the wall opposite the entrance was a large stone 'dresser' (it certainly resembles the ones which stood in many a house until the last century—in other words, the 20th). Whether or not it served such a mundane function in prehistoric times is less certain—they seem to have been designed for displaying something, symbolic objects perhaps, rather than simply for storage (Figure 4). Ample storage space was provided by a number of cupboards built into the walls. Between the hearth and the 'dresser' there was often a stone block, perhaps a "seat of honour". Near the dresser were rectangular stone boxes sunk into the floor. The corners were lined with clay to make them waterproof and Childe suggested that they were used to keep limpets. Limpets are very tough and practically indigestible to humans but they make excellent bait—as long as they have been softened by prolonged soaking in brine. Because of the general lack of wood, all of the other furniture was also made out of stone. On either side of the hearth were large rectangular stone boxes which must have served as beds (Figure 5). These would, of course, have been provided with mattresses of straw or heather along with sealskin covers. Sounds quite snug— especially if, as Childe believed, the taller slabs at the corners held bed curtains (Figure 6). In the earlier houses, such as House 9, the beds are built into the walls instead of projecting into the room as the later ones do (Figure 7). The bed on the right-hand side as one enters the room is invariably larger than the one on the left. Childe suggested that the distinction was gender-related, that the larger ones belonged to the men and the smaller ones for the women. He recovered beads and paint pots from some of the latter but we can be fairly certain that men wore jewellery and there is no real evidence to suggest that all potters were women. An equally convincing argument could be made that the women and children occupied the large beds and that the men slept on their own in the smaller ones. House 7: Interior Building 7 is somewhat isolated from the rest and is unique in that the door was apparently bolted from the outside—the cell where the bar was housed could only be entered from the passage (see plan, Figure 1). Naturally there is considerable debate about the significance of this. Obviously, it was designed to isolate certain people from the rest of the community—but on what grounds? Were they criminals or had they violated some taboo? Some communities have been known to isolate menstruating women or to set aside special 'birth houses'. Among many groups it was the practice to isolate groups of young boys or young girls who were approaching puberty as part of their 'rites of passage'. Beneath the right-hand bed, a stone-built grave was found containing the bodies of two women who had been buried before the house was built, possibly in some sort of foundation ritual. The slabs of the box bore a number of carvings, marking it off as someplace special. When the site was abandoned, a cattle skull was left lying on the left-hand bed. Building 8 sits all by itself on the west side of the village (Figure 8). It has a distinct appearance and, apart from the hearth, it has none of the usual furnishings—no beds, no limpet boxes and no 'dresser'. Instead, there is much more storage space and an additional room. Childe found a lot of debris from the manufacture of flint tools and burnt volcanic stones and so interpreted the building as a workshop. However, it may have had a more formal role as a meeting house for the community, possibly even involving ceremonial activities. Something of the sort is suggested by the amount of carved reliefs in and about the building Sherd of Grooved Ware Pottery Skara Brae is notable for the amount and variety of art produced. The same sorts of geometric patterns (chevrons, zig-zags, triangles, etc) can be found in the passages and Building 7, either built into the walls or in the fill. Broadly similar designs can be found on the pottery although, in this case, they also include curvilinear motifs (above). In addition to the bone and ivory jewellery mentioned above (Figure 2), a number of rather enigmatic carved stone objects have been found. These include two stone balls—one spherical (62mm in diameter) and incised with geometric patterns, the other (77mm in diameter) laboriously carved with knobs. There is an oval object (92mm long) with four knobs at each end and panels of carved decoration in the middle as well as a T-shaped object with incised decoration (Figure 9). They were found in different houses and in different contexts. They are most probably status symbols of some sort, conveying some sort of power and authority on those who held them. The village at Skara Brae was occupied for at least 600 years before it was finally abandoned sometime around the middle of the third millennium BC. Over the centuries that followed the sea steadily encroached on the site until it was finally buried beneath its protective layer of sand. Today Skara Brae is rightly considered one of the world's great archaeological treasures and has been carefully preserved by Historic Scotland.