Session 4 Teacher Notes

advertisement

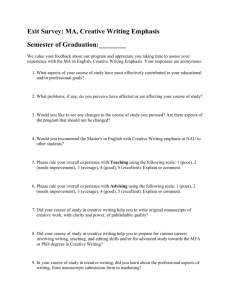

Session Four: Textual Criticism Recall the tree links in the chain from God to us. We have an inspired text; we have a canonical text. We now turn our attention to the way that the canonical text arrived at Berean Bookstore: transmission. POWERPOINT: God loves you illustration. The process through which one went to find original message would be textual criticism. We’re looking at the task, tools and techniques of textual criticism. I. The Task of Textual Criticism. What are we attempting to do? A. Defining Textual Criticism 1. General Definition “Textual criticism is the study of copies of any written work of which the autograph (the original) is unknown, with the process of ascertaining the original text.” 2. Higher vs. Lower Criticism Some have described the difference as standing above the text (higher) vs. standing underneath it (lower). Questions of Higher criticism: How did we get this text (before the version of it we have now)? Source: Who wrote this text and why did they write it? Form: How did this function in a community of faith? Tradition: What is the history of this text before it was written? Redaction: What was added or omitted in the compilation of this material? Who was the author? What sources contributed to it? When was it written? Question of lower criticism: What is the text? Textual criticism is lower criticism. Less suspicious attitude toward the text. B. Delivering the News POWERPOINT: 1. Bad News We do not have the original manuscripts. Furthermore, we have hundreds of thousands of variants. a. Autographs original manuscripts. b. Textual variants Differences which exist between texts. c. Response of the Believer Before we continue, it is important to consider the proper way to respond to this news. Some typical responses of believers and non-believers: 1) Refuse to even think about it. 2) Equate variant readings with unreliable text. POWERPOINT: 3) Become a KJV-only advocate (don’t mean to mock). POWERPOINT: 2. Good News a. The Types of Variants (from Lightfoot) 1) Trivial variations which are no consequence to the text. These represent the vast majority of variants. Matthew 11:10-23: Fourteen verses, nine variants. As you look at the many manuscripts which exist which contain these verses, nine differences. Seems like a lot. Then you look at the type of variants which exits: “for” and “the”. Spelling can be a pretty trivial variant as well. 2) Substantial variations which are of no consequence to the text. They are of no consequence because we can be confident they were not in original text. These are substantial variation—sometimes several verses—but as we look at the manuscripts, it becomes obvious which variant is in error. Example that we have looked at before: 1 John 5:7. Of all the Greek manuscripts, only two contain it (one from 14th or 15th century and one from 16th century. Two manuscripts have it in the margins. Probably came from a late version of the Latin Vulgate. 3) Substantial variations that have bearing on the text. These variations do cause us to wonder what the actual text was. Example: end of Mark. Evidence for: Two best uncial manuscripts (which we will examine later) don’t have it. Other manuscripts don’t include it. Stylistically it appears different, thematically may be different. Evidence for: many, many other manuscripts which indicate it was an early addition if an addition at all. Lightfoot notes: “Whatever the correct view, it is important to note that the truthfulness of this passage is not in dispute. The main events of Mark 16:9-20 are recorded elsewhere, so at any rate we are not in danger of forfeiting heavenly treasure. The variant readings in the manuscripts are nto of such a nature that they threaten to overthrow our faith. Except for a few instances, we have an unquestioned text; and even then not one principle of faith or command of the Lord is involved. b. The Date of Manuscripts “The earliest extant mss. of the N.T. were written much closer to the date of the original writing than is the case in almost any other piece of ancient literature” (Greenlee, 15). c. The Number of Manuscripts (Borop)—increases our confidence in which variants are right. “The number of available mss. of the N.T. is overwhelmingly greater than those of any other work of ancient literature” (Greenlee, 15). POWERPOINT Here is how the New Testament compares to other ancient writings*: Author Book Date Written Earliest Copies Time Gap # of Copies Homer Iliad 800 B.C. c. 400 B.C. c. 400 yrs. 643 Herodotus History 480-425 B.C. c. A.D. 900 c. 1,350 yrs. 8 Thucydides History 460-400 B.C. c. A.D. 900 c. 1,300 yrs. 8 Plato 400 B.C. c. A.D. 900 c. 1,300 yrs. 7 Demosthenes 300 B.C. c. A.D. 1100 c. 1,400 yrs. 200 Caesar Gallic Wars 100-44 B.C. c. A.D. 900 c. 1,000 yrs. 10 Tacitus Annals A.D. 100 c. A.D. 1100 c. 1,000 yrs. 20 Pliny Secundus Natural History A.D. 61-113 c. A.D. 850 c. 7500 yrs. 7 A.D. 50-100 c. A.D.114 (portions) c. A.D. 200 (books) c. A.D. 325 (complete N.T.) c. +50 yrs. 5366 New Testament From Josh McDowell’s New Evidence that Demands a Verdict. c. 100 yrs. c. 225 yrs. Aeschylus known by 50 manuscripts, Sophocles one hundred, Tacitus: Greek Anthology and the Annals of Tacitus one manuscript each, poems of Catullus in three manuscripts. A few hundred known mss. of works of Euripides, Cicero, Ovid, and Virgil. In the case of the N.T., in sharp contrast, there are over 4800 mss. in Greek, 8000 in Latin, and 1000 in other languages. As regard the time interval between the extant mss. and the autograph, the oldest known mss. of most of the Greek classical authors are dated a thousand years or more after the author’s death. The time interval for the Latin authors is somewhat less, varying down to a minimum of three centuries in the case of Virgil. In the case of the N.T., however, tow of the most important mss. were written within 300 years after the N.T. was completed, and some virtually complete N.T. books as well as extensive fragmentary mss. of many parts of the N.T. date back to one century from the original writings. 2. Summary Variants are: mostly trivial and can usually be solved with relative confidence due to early date of manuscripts and the number of manuscripts available. C. Determining the Task POWERPOINT Two charts on page 14. Obviously we have our work cut out for us! What do we have to work with? That is what we turn our attention to now. POWERPOINT II. The Tools of Textual Criticism. What do we use to complete our task? A. Types of Manuscripts We’re looking first at the different types of manuscripts on which we find portions of the Scripture. 1. Old Testament Why were there different manuscript families in the OT? In the NT in makes more sense due to the geographic expansion of the message, but what happened with the OT? We possess no manuscript prior to 400 B.C. “What can be readily demonstrated is that scribes had a determination to preserve the text. The text survived through all the disasters and devastations because the books were considered sacred and the scribes insisted on accurate transmission. There was a ‘psychology of canonicity’ which fostered a care and a concern for the preservation of the sacred writings.” Ross, 3. There are not a lot of manuscripts of the Old Testament, though more than most ancient works of literatures. With the NT, we believe we have a reliable text because there are so many that we can compare them with one another. In the OT, we believe that we have a reliable text because of the work of the scribes who were involved in its transmission. Changes we see take place from 400 B.C. onward: change script and linguistic features. Some seem to have attempted to create synoptic accounts. After exile, scribes alter script. More liberal scribes attempt to make changes for theological reasons: smooth over difficult passages, substitute euphemisms for vulgar descriptions, and remove the divine name. Ultimate result is three different “recensions.” a. Masoretic text 1) Scribes Hebrew scribes were extremely meticulous. If on one page a letter was unusually large, the copied page would make the letter large as well. If there was a word with an extra letter, that extra letter would be copied as well, though with a dot. Masoretes were scribes who labored for several centuries, beginning in about A.D. 500. 2) Manuscripts These were basically the only manuscripts of the OT available before the end of the nineteenth century. At that time there were less than 800 Hebrew manuscripts and they were virtually all from these Masoretic scribes. The earliest manuscripts we have from the Masoretic scribes are from the late ninth century (1890). 3) Lack of older manuscripts Why were there no older manuscripts? 1) age 2) Jewish practice of destroying bad or worn manuscripts 3) persecution. 4) Reliability of Masoretic text Why do we believe these are reliable? 1) Scribal accuracy. We have lots of evidence of regulations concerning the transmission of the canonical text. 2) As we see the duplication of texts w/in the texts we see word for word copying often. 3) Comparing the Masoretic text with earlier manuscripts which had been translated into other languages, i.e. the Septuagint (LXX), see great deal of accuracy. 4) Archeology b. Dead Sea Scrolls Remember that the earliest date of manuscripts we had prior to the 20th century was from the late ninth century. In 1948, a young boy was looking for his goat somewhere near the Dead Sea. Walking by the entrance of a cave, he threw a rock into the cavern. He then heard the sound of something breaking. Going into the cave, finds scrolls. Since that time, some 800 scrolls have been found. Dates from these scrolls pushes back the earliest manuscripts some 1000 years. The people who collected these scrolls were part of a group of Jews known as the Qumran community. Religious sect of Judaism from about the second century B.C. to the first century A.D. 2. New Testament a. Greek manuscripts 1) Autographs Original manuscripts 2) Papyri Earliest witnesses to the N.T. texts. About seventy known and classified. 3) Uncial Manuscripts Uncial is a type of writing (all caps, etc.). Papyri are written in uncial script, but this term refers to those on parchment. There are more than 250 of these in existence and they form the most important witness to the text. We would be remiss if at this point we did not recount the story of Codex Sinaiticus, one of the two most important uncials. In A.D. 550, Emperor Justinian built the Monastery of St. Catherine at the base of Jebel Musa, the traditional location of the biblical Mount Sinai. In 1844, a young man named Constantine von Tishendorf traveled to the monastery. Tishendorf, though only twenty-nine had already won some degree of prestige and fame for his abilities. He had gone to Paris in 1841 and deciphered the Ephraem manuscript. He was traveling throughout the East looking for manuscripts. In 1844, in a library at the monastery, he finds a huge basket full of old parchments with the OT in Greek. “The most ancient I had ever seen.” To his great dismay, he discovers that these papers were “committed to the flame” (going to the oven). Asks if he can have some. They say yes, but he gets so geeked out that they only let him have forty-three sheets (1/3). He returns home and publishes what he has found. In 1853, he returns to the monastery and can learn nothing further about the manuscript. In 1859, he goes again and can find nothing. The day before he’s to leave, he presents a copy of the manuscript he had translated to the Steward of the monastery. The steward remarks that he has one of those two and casually pulls out of a closet in his cell a manuscript wrapped in red cloth. Tish had learned his lesson and this time just casually asks if he can look at the manuscript in the evening. Permission is given and he spends all night studying the manuscript. Amazingly, not only is it a copy of the OT in Greek.. it contains the NT as well! Tish worked for many years to slowly gain access ot moe and more of the codex. Eventually, Tish basically negotiates the sale of the codex to the Czar of Russia. In the 30’s, the USSR sales the codex to the British museum for about ½ million dollars, where it is to this day. 4) Miniscule Manuscripts Largest group of Greek NT manuscripts, dating from the 9th century. Use miniscule handwriting. “Being later than the uncials, most of the miniscules may be assume to have a text which is inferior to the uncials. This, however, is not always true. A twelfth-century miniscule, for example, might be only half as many copies removed from the autograph as an eighth-century uncial, and might also have an ancestry of more accurate copying” (Greenlee, 42). 5) Lectionaries These are manuscripts which contain Scripture readings. Fragments from 6th century, complete manuscripts from the eighth century. b. Translations 1) Latin translations Old Latin: Greek N.T. had been translated by A.D. 180. jchastant@yahoo.com Major translation is the Vulgate—Translated by Jerome towards ends of 4th century. The story of the vulgate proves an interesting truth regarding translations in general. Jerome works to get his translation accurate and in so doing, makes changes. Not well received—how could he replace the LXX? Not to mention other Latin translations. That’s typical of translations. Erasmus, King James Version, NASB (for me), NIV. 2) Syriac 3) Coptic (Egyptian) 4) Armenian 5) Georgian 6) Ethiopic 7) Gothic 8) Arabic 9) Persian 10) Slavonic 11) Frankish c. Church Fathers B. Manuscript Families What is the difference between manuscript families and types of manuscripts? Types of manuscripts are the actual texts. As we look at all of the different types of manuscripts, we are able to discern similarities between. Those which have a great deal of similarity become part of the same manuscript families. We can then begin to do some detective work to ascertain how different additions or deletions came to be in a certain text. To put it another way, in the first section, it was as if we were laying a whole bunch of papers on the table and describing the types of paper in the first section. Some were big, some small, some were just scraps of paper. Now, here in the second part, we’re start looking for common characteristics among these different types of papers. So, you may have two yellow, legal-sized papers but they have less in common with another than they may with some other document on a completely different type of paper. Our goal, of course, is to be able to determine what the original text was. 1. Old Testament Despite the reliability of the scribes, we do have evidence that some scribal revisions took place. 1) Script changes, there were some liberal scribes: 2) Attempts to harmonize passages (intentional and unintentional), 3) smooth out difficulties, 4) tone down vulgar language with euphemisms. Different scholars, as they look at the textual evidence (types of manuscripts), see different family groups. One has hypothesized three major family groups. a. Masoretic Text We’ve explored the Masoretes and their text before. These were manuscripts types—it should come as no surprise that they also comprise a family. b. Samaritan Pentateuch This manuscript familiy was known to some of the early church fathers, but not made known in the west until the 17th century. Fall of N. Kingdom to Assyria in 722 B.C. People from the East marry those who remain in the land. Foreigners develop a form of worship similar to Jewish faith. The S. Kingdom returns from exile, refuses to reunite with Samaritans. Samaritans build a temple on Mount Gerizim (4th century B.C.). Samaritans hold the Pentateuch as Scripture. Count only the Pentateuch as authoritative. Large degree of agreement between Masoreic text and Samaritan. Major differences deal with particular views of the Samaritan community (Deut. 27:4—Ebal replaced with Mount Gerisim). c. Septuagint (LXX) When Jerusalem fell in 587 B.C., Jews were scattered. A large number go to Egypt (see this in the book of Jeremiah—he is forced to emigrate there). Alexander the Great founds Alexandria in 332 B.C. and Jews make up an important part of the society. Jews learn Greek in order to function in society. Legend: In the mid 3rd century B.C., seventy-two scholars translate from the Hebrew to the Greek in seventy-two days. This is the version used by the NT authors. NOTE: the use of a translation (an imperfect translation) by NT authors. Certain variants that are in LXX that make their way through various traditions. LXX is also important due to help in understanding NT Greek. d. Aramaic Targums Date: Pre-Christian times-unofficial targums exist. Written Targums exist from 5th century A.D. Hebrew people switch languages when they return from exile. Targum means “translation” or “paraphrase.” Character: Attempt to incorporate oral tradition with the text. Example of Ruth: And Ruth said: Do not urge me to leave you, to turn back from following you, for I wish to become a sojourner [proselyte]. Naomi said: We are commanded to keep the Sabbaths and the holy days, so as not to walk more than 2000 cubits. Ruth said: Wherever you go, I will go. Naomi said: We are commanded nto to lodge together with the Gentiles. Ruth said: Wherever you lodge, I will lodge. Naomi said: We are commanded to keep the 613 precepts. Ruth said Whatever your people observe, I myself will observe (Ewert, 103). All are represented by the DSS. 2. New Testament POWERPOINT: Geographical locations of each manuscript family. a. Alexandrian Text Comes from Egypt, most important family. The two major uncials come from this family: Sinaiticus (Tishendorf’s manuscript) and Vaticanus. b. Byzantine Text Adopted in Constantinople and is the common text of Byzantium. Used by Erasmus and KJV translators. Documents from this family are older than the Alexandrian manuscripts, but there are more of them. Textus Receptus—majority text. c. Western Text Used by early church fathers, but not that reliable. d. Caesarean Text Seems to have arisen out of the Alexandrian Text and was mixed with the Western text. Widely used in Caesarean. e. SO WHAT???? Contemporary Relevance What is the most reliable English translation? How you answer that question depends upon which family or families of manuscripts you believe are most reliable. 1515, Erasmus produced the first Greek NT. Compiled documents, some of which are unreliable. Problems: 1) unreliable documents, 2) translated some missing portions from the Latin vulgate (Example: last page of Revelation was missing, so he takes the Latin and translates it into Greek). 3) It’s a hurried translation. This version continues to be reproduced, instead of other versions which were more carefully compiled. One edition, published in 1633, in its preface boasts that the reader “has the text which is now received by all, in which we give nothing changed or corrupted” (Metzger, 106). “Thus from what was a more or less casual phrase advertising the edition (what modern publishers might call a ‘blurb’), there arose the designation ‘Textua Receptus’, or commonly received, standard text.” Establishes itself as “’the only true text’ of the NT, and was slavishly reprinted in hundreds of subsequent editions. It lies as the basis of the KJV and of all the principal Protestant translations in the languages of Europe prior to 1881” (106). The KJV and the NKJV follow the Textus Receptus, or Majority Text. Almost all other translations use more critical criteria to determine the text. www.gospelcenterchurch.org POWERPOINT III. The Techniques of Textual Criticism. What methodology do we employ? We have time for just a brief overview of the process of textual criticism. These are from Metzger’s The Text of the New Testament. A. External Evidence 1. The date of the witness. 2. The geographical distribution of the witnesses that agree in supporting a variant. Of course, one must ascertain that the witnesses are truly independent of one another. 3. Genealogical relationship of texts and families of witnesses. Witnesses are to be weighted rather than counted. [What does this mean? Do you agree or disagree?] B. Internal Evidence 1. Transcriptional probabilities depend upon considerations of palaeographical details and the habits of scribes. [Palaeography: the consideration of the processes involved in the making and transcribing of manuscripts.] 2. Intrinsic probabilities depend upon considerations of what the author was more likely to have written, taking into account: a. the style and vocabulary of the author throughout the book, b. the immediate context, c. harmony with the usage of the author elsewhere, and, in the Gospels, [why the Gospels?] d. the Aramaic background of the teaching of Jesus, e. the priority of the Gospel according to Mark, and f. the influence of the Christian community upon the formulation and transmission of the passage in question.