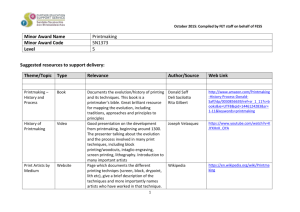

PrintopiaHowAndWhyDoArtistsPrint

advertisement

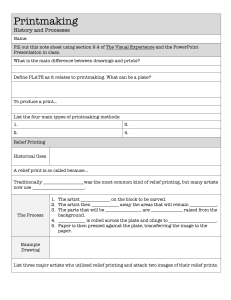

Printopia: How and Why do Artists use print? In contemporary art, artists can accumulate different roles; fragmenting and adapting other art works, printmaking, performing, photography and filmmakingare just a few strategies available. Successful artists from Ai Wei Wei to Anselm Kiefer and Damien Hirst aremulti channel entrepreneurs. Print is part of the mix. The Industrial Revolution had a huge impact on art and artists. During the nineteenth century, painting and sculpture came to be seen as extensions of the artist’s body, and highly individual. The work of an artist was not ‘alienated’ - in contrast to industrial factory labour. As publishers became adept at reproducing mass media images, some artists seemed to move backwards, seeking out the special qualities of prints made by hand, particularly etching. The technique had been widely adopted to make fine prints available to a growing audience of art collectors.The 19th century vogue for printmaking introduced the world to new ‘limited edition’ marketing techniques. The distribution of prints to middle class homesgave printmakers the choice to produce a very limited or much larger print run. In the 20th century, printmaking, with its portability, flexible formats, relative affordability, and collaborative environment, was a catalyst in exchanging ideas. It was also a focus for the articulation of political resistance. For 21st century artists, printmaking has a number of advantages and applications. Contemporary artists like Jeff Koons eliminate traces of manual work. The audience no longer sees the interaction between artist and materials as a critical part of an art work. However, in printmaking these interactions are often very important- the production of slightly different multiples; experimenting with different versions, working collaboratively - can all be advantages. In a world where so much cultural content is freely and anonymously available, the possibility for individual printmakers to retain control of authorship and speak to audiences directly is attractive. Increasingly, printmakers can be seen as part of the collaborative ‘Maker’ community, as well as part of the fine art world, with print studios sometimes also functioning as ‘makerspaces’. Intaglio ‘Intaglio’ comes from the Italian ‘intagliare’ meaning to engrave. Developed in Europe following the introduction of block printing from China, Intaglio has its origins in the decorative metalwork techniques used by fourteenth century jewellers and armour makers. The term is used to describe a ‘family’ of print techniques employed by artists exploiting the principle that ink, trapped in small groves in a metal plate, can be transferred to paper under extreme pressure. The incised line or sunken area holds the ink – so intaglio is the opposite of a relief print. Etching While the drawing styles, and artistic interests Lucien Freud (4) and Peter Klucick (1) differ significantly, they share a common approach - drawing with a needle to scratch fine lines into a protective coating covering a metal sheet. When the metal plate is immersed and etched in acid these fine lines are 'eaten away' to create thin grooves that trap the ink that is subsequently transferred to paper. Paula Rego (5) and Frederic Morris (2) use a variant of the etching process called aquatint,which employs a fine acid resistant powder to create tonal effects similar to the qualities of watercolour. Tonal variation is achieved by leaving unprotected areas of the plate in the acid for different lengths of time. The longer the plate is submerged in acid the deeper the 'bite' and darker the printed tone. Mezzotint Aoife Layton (6) employs a technique called mezzotint (from the Italian mezzotinto meaning half-tone) in which the plate surface is roughened to hold an even quantity of ink that will print as a pure dense black. The image is then produced by progressively smoothing the plate surface to create increasingly lighter tones. Images made by this method are typically set against a dark background and consist of tone without lines. Polymer Images transferred to the printing plate photographically can also be printed by the intaglio process. Nicola Thomas (7) employs a contemporary industrial material, polymer plates, to create images with the intention to 'recapture, reinterpret and renew familiar narratives'. Relief Prints Relief printing directly from a carved surface was invented in China circa 100 A.D. It travelled to the west in the fourteenth century, andis still commonly used by artists today. Paul Peter Piech (9) used lino to produce bold low cost posters with minimal use of colour. Anita Klein (7, 8) also uses lino to develop more complex colour combinations in striking images of everyday life and domestic intimacies. Following its use by Swedish artist animators at Rorke’s Drift, in the 1960s, an arts centre was established in Zulu Natal next to the battlefield. At this centre, a number of artists developed their work primarily through print, producing black and white lino prints with a strong social commentary - part of the struggle against apartheid.Southern African artists gained international recognition for their work. More recently, Namibian artists, including Papa Shikongeni (10) have continued this tradition producing extraordinarily vibrant prints, substituting cardboard for relatively expensive lino, frequently using domestic paint instead of ink, and employing a bag as their printing press. 19th and 20th Century Print Revivals Rapid technological progress in the nineteenth century printing industry made earlier print techniques obsolete. Printing now because a serious pastime for wealthy and middle-class hobbyists, including Queen Victoria. This development corresponded to the use of etching among artists such as the Barbizon School who worked directly from nature. This movement flourished from the mid nineteenth century to the depression of the 1930s, and laid the foundations of contemporary artists' printmaking. A marketing strategy was developed to increase values by artificially limiting edition numbers, and 'Won't you come up to see my etchings?' became a saucy catch phrase. Following the Wall Street Crash in 1929, artist’s printmaking virtually collapsed until its resurgence in 1960s pop culture. In the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, staff at the Havana branch of the J. Walter Thompson advertising company pledged their support to the new regime. This gave rise to a 'branding' strategy that employed pop-style imagery to promote the ideals and culture of the 'New Cuba'. The posters by painter and graphic artist Raul Martinez (12) are some of most widely know examples of this genre. Ironically, Martinez undertook this work as a freelancer after not being permitted to teach because of his homosexuality. During the 1960s and 70s, screenprinting, which provided the capacity to make large scale brightly coloured posters and works on paper for little capital investment gained popularity as a medium for protest and social activism internationally. The feminist group See Red (11) was one of a number of Londonbased groups that emerged during this period. Paddington Printshop (now londonprintstudio) co-founded by John Phillips (13) was another organisation making socially engaged work in west London. In the mainstream, many artists including Joe Tilson (19), turned to screenprint, and pop imagery. These were often accompanied by experiments with 'multiple' artworks created through industrial processes such as vacuum forming. Painters such as Sandra Blow (27) worked closely with production studios to create prints that competed in impact and scale with painting on canvas. 3D Printing Ronald King (17) frequently employs embossing and die cutting to create 3 dimensional prints and books and Fiona Hepburn (14,15,16) uses assembly to construct individual objects from scores of printed objects. Artists at the Centre for Fine Print Research, UWE (18) have been exploring the creative potential of three dimensional printing. The following artists are included in the display cabinet:- David Huson, Katie Vaughan, Stephen Hoskins, Verity Lewis, Peter Walters, Katie Davies and Peter Ting. Scarabs 2014-15 Designed and printed by David Huson and Katie Vaughan Artefacts from a research project into the 3D printing of ceramic bodies investigating the possibilities of using techniques developed by the ancient Egyptians to produce a 3D printed ceramic body that will glaze itself during a single firing process. The two methods used in ancient Egypt to enable self-glazing in one firing are efflorescence glazing and cementation glazing. Lattice Pyramids 2014 Designed by David Huson The Pyramids have been 3D printed in a University of the West of England patented porcelain ceramic material and are biscuit fired and glazed in the conventional manner. Deruta Bowl 2014 Designed by Stephen Hoskins Inspired by hand-decorated majolica bowls from the 16th century Italian school of ceramics, this early digitally-printed research piece by Hoskins was a 2dimensional development of the underside of an Italian Renaissance bowl. Skull 2011 Designed by Verity Lewis with Peter Walters and David Huson Printed in plaster The Skull is a test piece in 3D printing. Object and Illusion in Print 2010 Designed by Peter Walters Printed in plaster . Vela Pulsar 2010 Polyamide 3D print Designed by Peter Walters and Katie Davies This sculpture was created through the transformation of astrophysical data into tangible 3D form. The sculpture was 3D printed from a signal, detected by a radio telescope, which emanates from a distant star – a pulsar – located in the constellation of Vela, some 950 light years from Earth. The resulting 3D printed sculpture is a translation of the signal from the pulsar – a 3D manifestation of the pulsar itself, and a direct translation of sound into visual representation. Bristol Teacup 2011-12 Designed by Peter Ting and printed by Peter Walters and David Huson This double walled, pierced teacup has been 3D printed in a University of the West of England patented porcelain ceramic material and biscuit fired and glazed in the conventional manner. Lithography Following the invention of lithography in the late eighteenth century, printmaking and the graphic arts were transformed. Based on the incompatibility of water and oil, and utilizing a polished limestone block as a substrate on which to draw, lithography was the first printing process to truly capture and reproduce the expressive qualities of hand drawn images and rich tonal variety. The most famous images using this process are Toulouse-Lautrec’s colourful posters of Parisian night life. Stone lithography continued to be used commercially well in to the twentieth century when it was displaced by photographic methods of reproduction. The technique survived due to the dedication of a handful of artist practitioners and master printers and saw considerable revival in the pop art movement in America. Sadly in the UK teaching and support for the technique has dwindled and apart from londonprintstudio, very few open access studios offer training and access to this exciting medium. The surface of the stone is chemically altered so that the image area becomes attracted to grease, and the non-image area becomes attracted to water. Unlike intaglio or relief printing, where the physical surface of the plate or block in changed, in lithography, it is the chemical nature of surface that is changed. This is how it got the name “chemical printing”. In this exhibition we see a variety of approaches to the direct drawing opportunities provided by the medium in the work of Meg Buick (24) Sarah Duncan, Beauvais Lyons (22) , Darren van der Merwe (21), Robert Miles (20) and Lucy Farley (23) along side the photo litho work of Sarah Duncan (25) Digital Printmaking During the past two decades technological developments in inkjet printing have opened new creative possibilities enabling artists to edit, reconstruct or otherwise fabricate photographic 'realities' as in the work of Jo Ganter (28) and Rebecca Beardmore (29) or as in the print by James Faure-Walker (26), to draw directly into the computer software. Thérèse Oulton (30,31,32,33,34,35,36) The exhibition includes a small selection of works in screenprint, monoprint, intaglio and inkjet, by just one artist Thérèse Oulton. These works, some made at the studio, show how these different media can be manipulated to bring a subtly different emphasis to an individual hand.