Six Elements of a Good Argument

advertisement

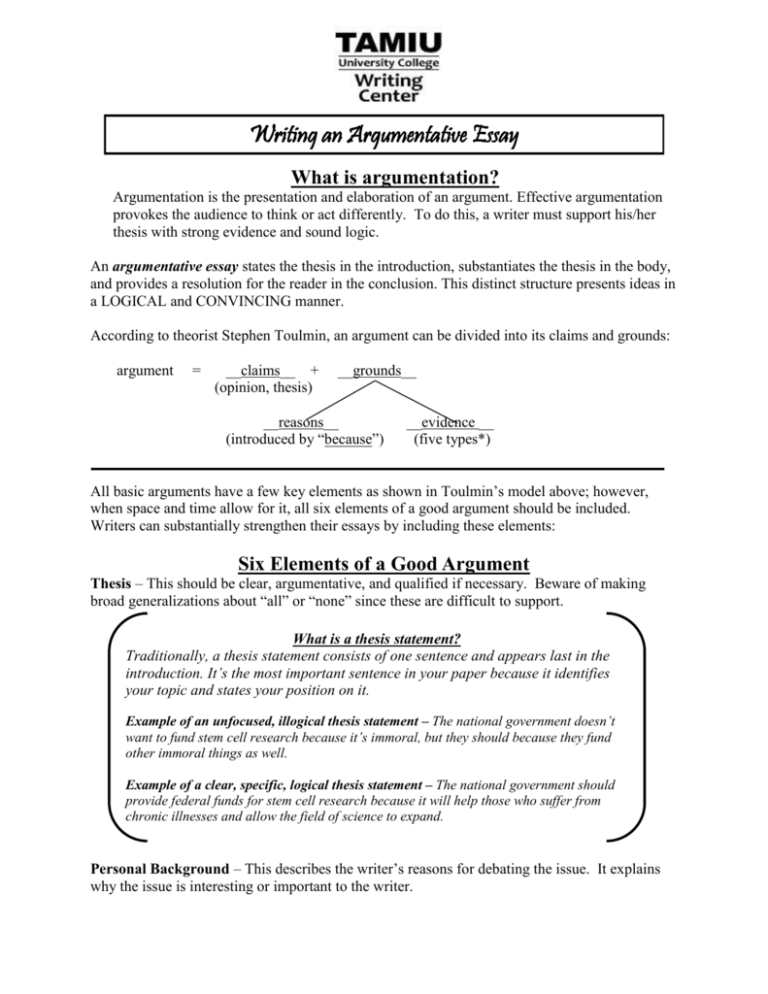

Writing an Argumentative Essay What is argumentation? Argumentation is the presentation and elaboration of an argument. Effective argumentation provokes the audience to think or act differently. To do this, a writer must support his/her thesis with strong evidence and sound logic. An argumentative essay states the thesis in the introduction, substantiates the thesis in the body, and provides a resolution for the reader in the conclusion. This distinct structure presents ideas in a LOGICAL and CONVINCING manner. According to theorist Stephen Toulmin, an argument can be divided into its claims and grounds: argument = __claims__ + (opinion, thesis) __grounds__ __reasons__ (introduced by “because”) __evidence __ (five types*) All basic arguments have a few key elements as shown in Toulmin’s model above; however, when space and time allow for it, all six elements of a good argument should be included. Writers can substantially strengthen their essays by including these elements: Six Elements of a Good Argument Thesis – This should be clear, argumentative, and qualified if necessary. Beware of making broad generalizations about “all” or “none” since these are difficult to support. What is a thesis statement? Traditionally, a thesis statement consists of one sentence and appears last in the introduction. It’s the most important sentence in your paper because it identifies your topic and states your position on it. Example of an unfocused, illogical thesis statement – The national government doesn’t want to fund stem cell research because it’s immoral, but they should because they fund other immoral things as well. Example of a clear, specific, logical thesis statement – The national government should provide federal funds for stem cell research because it will help those who suffer from chronic illnesses and allow the field of science to expand. Personal Background – This describes the writer’s reasons for debating the issue. It explains why the issue is interesting or important to the writer. Historical background – To more effectively communicate an argument, writers must provide the audience with the context for that argument through historical facts of the issue. Common ground – These are points related to the issue and on which both sides agree; identifying them generates good will between the writer and reader and helps avoid arguing points on which both sides already agree. Definitions – Writers must define the common or technical terms they use in an essay for the average reader to understand. A term can be defined by stipulating a definition, by using a synonym, or by offering an example. Arguments Arguments that oppose the thesis should be stated and explained in a way that opponents (the readers for whom the argument is intended) would accept. Generally, the writer should respond to arguments that oppose the writer’s thesis in one of three ways: by conceding, refuting, or clarifying. Arguments that support the thesis must include reasons (for supporting the thesis) and evidence to substantiate those reasons. The most convincing and best-developed arguments should generally be saved for the end. Structuring an Argumentative Essay Introduction Catches the reader’s attention Introduces the issue States the thesis *See also “Methods for Developing Introductions” handout. Body Contains two or more well-developed paragraphs that provide reasons and evidence for the argument. These paragraphs include the following: Topic Sentence (reason) Evidence Linking Sentence Second piece of evidence Linking Sentence Third piece of evidence (if necessary) Linking Sentence Concluding Sentence *See also “Developing Body Paragraphs” handout. Conclusion What are the five types of evidence*? Real life examples - an actual event observed or experienced Statistics - numbers Authorities - experts identified by name & with credentials Analogies - comparisons Hypothetical situations - imagined or created situations (*See also the “Providing Evidence” handout.) Provides the audience with a resolution (e.g. refer to the introduction, call for action, issue a warning, etc.) Restates but does not repeat the thesis *See also “Methods for Developing Conclusions” handout.