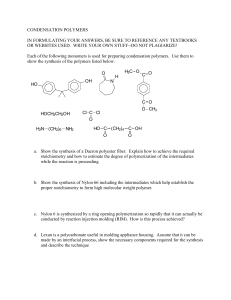

The Discovery of Nylon The announcement in October 1938 of the discovery of nylon, the first completely synthetic fiber, and the imminent production of nylon stockings was a momentous occasion. The press was fascinated by a fiber described as “strong as steel” and made from nothing more than coal, air, and water. And the public was eager to see stockings made from a fiber that it thought, being as strong as steel, must last forever. From our perspective, the discovery of nylon was important because it was the beginning of the synthetic polymers industry. Its discovery also established the study of polymers as a basic science. Wallace Hume Carothers, the discoverer of nylon, was 31 years old in 1928 when he left Harvard University for the DuPont Company. (He had obtained his Ph.D. four years earlier in organic chemistry at the University of Illinois.) DuPont had decided to establish a group devoted to fundamental research, an idea that was rather novel at the time. The plan was that Carothers would work in an area that, though potentially useful to the company, did not have to have immediate commercial application. Carothers proposed to work on the structure of materials like rubber, silk, and wool. The German chemist Hermann Staudinger had earlier suggested that these materials were actually macromolecules (that is, huge molecules) consisting of long chains of similar groups of atoms (in other words, polymers). At the time, most chemists thought that these materials were composed of aggregates of many small molecules held together by some unknown force that was different from the normal forces of chemical bonding. Carothers felt that he could determine the truth of Staudinger’s view by using the methods of organic chemistry to synthesize (or build up) macromolecules in such a way as to establish their structure. He had a simple but brilliant idea. To understand Carothers’s idea, consider two functional groups, such as a carboxylic acid group (COOH) and an alcohol group (OH), that chemically link together. We can write a reaction between two compounds containing these groups forming an ester this way: 1 Even more simply, we can represent the linking of functional groups, such as a carboxyl group and an alcohol (or amine) group, as the linking of a hook and eye (the functional groups). Now suppose we find a molecule having two of the same functional groups (such as two carboxyl groups) at the ends of the molecule; this would be the equivalent of a molecule with hooks at both ends. Then the reaction of several such molecules would result in a larger molecule. With many such molecules, the product would be a long- chain molecule - a macromolecule. Carothers felt that if he could synthesize such a macromolecule with the properties of a textile fiber, he could establish the basis for further study of natural polymers, and he could go on to develop synthetic polymers (such as nylon) with improved properties. Carothers’s first macromolecule of this type was a polyester prepared from two different molecules, a dicarboxylic acid (a molecule with two carboxylic acid groups) and a dialcohol (two alcohol groups). The product, although interesting, tended to decompose in hot water and had a low melting point, so as a fabric it would hardly withstand washing or ironing. For his next experiments he prepared a series of polyamides, each from a dicarboxylic acid and a diamine. One polyamide from this series, called nylon-6,6, had properties that were promising. (The 6,6 refers to the number of carbon atoms in the dicarboxylic acid and the diamine, six in each case.) At this point, other teams at DuPont developed nylon-6,6 as a fiber that could be spun into hosiery. Carothers might well have been awarded the Nobel Prize for his outstanding contributions to chemistry. In less than ten years, he had established synthetic polymer science and had discovered neoprene rubber and polyesters, as well as nylon. He had numerous interests, including politics, music, and sports, and he also prided himself on his writing skills. Unfortunately, Carothers had been troubled since youth with more and more frequent bouts of depression. After the discovery of nylon, he went into a severe depression, feeling he was a failure as a scientist. On April 29, 1937, he committed suicide by drinking lemonade containing potassium cyanide. His death was a tremendous loss. 2