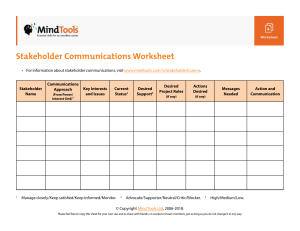

Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 1 The authentic corporate citizen: The role of relational transparency and stakeholder relationship cultivation strategies Corné Meintjes University of Johannesburg ABSTRACT Corporate scandals have influenced stakeholder trust globally. Corporate governance efforts to curb scandals have failed to improve company behaviour, resulting in pressure on society and stakeholders. A stakeholderoriented relational approach to corporate citizenship is non-negotiable – it requires authentic companies to use cultivation strategies to build authentic stakeholder relationships. Companies’ integrated reports illustrate their authenticity and ability to present balanced information. The integrated reports of selected JSE-listed South African companies were analysed through quantitative and qualitative content analysis. Relational transparency was found to be central to a company engaging authentically with stakeholders, evident through company behaviour and integrated reporting. However, companies do not focus enough on relational transparency and lack strategies that require active involvement with stakeholders. Such strategies include task-sharing, openness, assurances, positivity and networking. Stakeholder relationships are dependent on a company’s cultivation of authenticity and inclusivity. The proposed framework for authentic company stakeholder relationship networks could help companies to understand authenticity in stakeholder relationships. ______________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Given the need for societal engagement beyond customer and shareholder interest (Kruggel, Tiberius and Fabro, 2020), corporate citizenship is no longer a ‘nice-to-have’. Yohn (2020) notes that companies need to live up to higher public expectations while remaining under increased pressure to add value to society through their business practices and social responsibility efforts. This tension comes as governments are no longer seen as the exclusive social change agent to redress the past’s injustices (Flores-Araoz, 2011). Unfortunately, distrust exists among company stakeholders (Weibel, Sachs, Schafheitle and Laude, 2020), which affects company reputation. This is because of the scandals and misconduct that include dishonourable and reckless business practices (Badenhorst-Weiss, Bimha, Chodokufa, Cohen, Cronje, Eccles, Grobler, Le Roux, Rudansky-Kloppers and Botha, 2016). Highlighted scandals include, but are not limited to, Enron, Merrill Lynch and Martha Stewart in the US; Cadbury Nigeria Plc, Spring Bank PlC, Wema Bank Plc in Nigeria (Ogbodu and Umoru, 2018); and, KPMG, Transnet, McKinsey, Standard Chartered, HSBC, SAP (The Economist, 2017; Nyamakanga and Diphoko, 2017), Steiner, Tongaat Hulett, VBS Bank, McKinsey and Company, Eskom, Bosasa, and Gold Fields (Business Insider SA, 2020) in South Africa. Corporate governance efforts have increased globally with interventions such as the UK Corporate Governance Code of 2009, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in the US, and the King Reports in South Africa. However, these do not seem to have the desired effect on improving corporate behaviour and citizenship (ACCA, 2020), while pressure continues to mount from society and consumers (Ashcroft, Childs, Myers and Schluter, 2016; van Coppenhagen and Naidoo, 2017). Corporate governance, as stakeholder management, is a response to these societal expectations of corporate citizenship (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016; Rendtorff, 2020). Corporate citizenship refers to a company’s role and responsibility towards society (Maignan, Ferrell and Hult, 1999). In other words, it is the contribution of the company to the common good of society (Rendtorff, 2020). Although the metaphor of citizenship emerged as early as 1886 where corporations’ rights were equated to that of a natural person, research papers only started to appear in the late 1960s (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016; Kruggel et al., 2020). During the 1980s, mention was made in management literature of companies’ social role, while during the late 1990s, companies increasingly devoted attention to corporate citizenship initiatives (Maignan et al., 1999). 2 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 During this time, companies became aware of their changing roles and responsibilities, and corporate citizenship was introduced into the corporate social responsibility discourse (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016). However, corporate social responsibility was seen as a luxury ‘add-on’ that only the most successful companies could afford (Freeman and Mcvea, 2001). At the start of the new millennium, serious scholarly discourse gained momentum (in 2004) on the first big corporate scandal, Enron (2001). At the same time, corporate citizenship research emerged in South Africa with the Sustainability Institute at Stellenbosch University offering a course in corporate citizenship in 2003; the University of South Africa (Unisa) establishing a Corporate Citizenship Unit in the same year; and the first academic conference on corporate responsibility was held in 2005 (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016). However, at the start of 2010, corporate citizenship initiatives have become less effective as some companies use these initiatives to garner favourable publicity, rather than to act authentically to help society (Hoeffler, Bloom and Keller, 2010). Greenwashing, which occurs when a company focusses on environmentally orientated corporate social responsibility activities, is self-serving window-dressing (Delmas and Burbano, 2011) and a typical example of what Hoeffler et al. (2010) refer to. In the US, the Boston College Centre for Corporate Citizenship ‘2016 State of corporate citizenship’ study found that those companies who aligned their citizenship programmes with their business objectives reported deeper customer and employee engagement; addressed environmental and social issues that could have disrupted their business; and created reputational assets while contributing to the common good among others (Stangis and Smith, 2017). In a study in 2018 by Changing Our World Inc., it was found that 75 per cent of people think companies are more talk than action when supporting social issues. However, stakeholders see companies that make a difference by leveraging their unique business assets as authentic (Changing Our World Inc., 2018). Academically, corporate citizenship research has stagnated although it has a rich publication landscape mainly studied in business, ethics, management, political science and environmental studies. Most research originated from the US (32 publications), England (16 publications) and Germany (11 publications) (Kruggel et al., 2020). Little academic research has emerged from Africa or South Africa (Visser, 2005; Kruggel et al., 2020), with papers focussed on related ideas such as individual ethics (Roussouw 1994, 1997, 1998, 2000; Abratt and Penman, 2002), the Social Responsibility Index (Sonnenberg, Reichardt and Hamann, 2004), stakeholder theory (De Jongh 2004), corporate governance (Jeppesen and Granerud, 2004) and sustainability reporting (Visser, 2002; Sonnenberg et al., 2004). Visser (2005) notes that private institutions, rather than academics, conducted the most comprehensive research on South Africa’s corporate citizenship. Similarly, research on authenticity, corporate citizenship and stakeholder relationships was mainly led by private institutions (ACCA, 2019, Tepper, 2019; Hewitt, 2020; Nooyi and Govindarajan, 2020). As part of the corporate citizenship debate, greater emphasis has been placed on stakeholder relationships in response to shifts in the corporate world (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016, Rendtorff, 2020). Further importance is now placed on inclusivity, sustainability and integrated reporting with the establishment of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the King Reports in South Africa (King, 2016). A report released in 2018 assessing the annual reports of all the companies in the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 Index indicated that truthful and authentic communication plays a key role in building trust. This report highlighted that authenticity is about more than being fair – it is about transparency, being honest and open and telling the company’s story truthfully (Black Sun, 2018). The IIRC considers a company’s capacity to illustrate its authenticity by presenting balanced information in its integrated reports. The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) found that impressions management, which is the willful or unintentional process in which companies endeavour to influence stakeholders’ perceptions about an issue, played a role in how companies report positive performance more prominently than negative performance (2019). Companies were found to offer general information on risks and opportunities, ultimately affecting trust and reputation among stakeholders (ACCA, 2019). With the release of the third King Report in 2009, South African companies that had adopted the reports’ principles were considered among the best-governed in the world’s emerging economies (Institute of Directors, 2009). Since then, however, the country has seen several governance-related scandals such as Steiner, Tongaat Hulett, VBS Bank, McKinsey and Company, Eskom, Bosasa, and Gold Fields (Business Insider SA, 2020). This raises the question of whether companies are authentic and reporting on their authentic stakeholder relationships, which in turn affects whether they are perceived as good corporate citizens. It is not clear whether South African companies emphasise cultivating stakeholder relationships as part of their efforts to be authentic. Therefore, this study aimed to analyse the integrated reports of selected South African companies to gain insight into how they report on their authenticity and stakeholder relationship efforts. These insights will help companies understand corporate citizenship and the role of being authentic in cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships. As an integral part of society, stakeholders will consequently be able to view their expectations and needs in the context of the authentic company, resulting in a deeper appreciation for the complexities that companies face. Based on these insights, a framework is proposed for understanding an authentic stakeholder network. Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 The remainder of the article is structured as follows: First, the research’s theoretical orientation is outlined, followed by a discussion on corporate citizenship, authenticity, and authentic stakeholder relationships. A description of the analysis of the integrated reports of JSE-listed companies follows before presenting and discussing the findings that led to the proposed framework presented in this article. THEORETICAL ORIENTATION Research regarding stakeholder theory has intensified over the past 30 years, resulting in new theoretical propositions. This extends the traditional stakeholder management research to ‘emphasise the optimistic view of human beings and develop a stakeholder-oriented relational approach that is based on kindness, honesty, and positive values’ (Civera and Freeman, 2019: 41). There is a focus in stakeholder theory to consider what a company should or should not do with its stakeholders. This means that companies should consider stakeholders to foster relationships, cooperation, and individuality of stakeholders, including the interdependency among all the stakeholders in the network (Salvioni and Astori, 2013; Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks, 2016). Edward Freemans’ 1984 publication Strategic management – A stakeholder approach had the mutual influence and impact of stakeholders on one another in mind (Civera and Freeman, 2019), proposing a more pragmatic and honest way of engaging with stakeholders (Rendtorff, 2020), which is the foundation of this article. Network theory underpins this research from a stakeholdermanagement perspective (Rowley 1997; Friendman and Miles, 2006). The basic premise of network theory is that companies exist in a complex social network. They try to navigate multiple, interdependent stakeholder interests and predict their reactions to competing stakeholder demands. The theory highlights that companies do not respond to one stakeholder group at a time and that the relationship structures between companies and their stakeholders influence management decisions. Thus, companies are not always the nexus of interactions between stakeholders (Yang and Bentley, 2017). Instead, it points to the network of stakeholders with the company as a stakeholder itself (Rowley, 1997; O’Conner and Shumate, 2018). Stakeholder-relationship thinking aligns well with network theory in that the company is not necessarily the central actor but is instead part of creating value with stakeholders through an emergent process (Civera and Freeman, 2019). Corporate citizenship Corporate citizenship is a means to link companies, society, the economy and the environment to operate sustainably (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016). There are various viewpoints of corporate citizenship, including the limited, equivalent and extended views. The limited and equivalent views of corporate citizenship merely link it with philanthropy and corporate social responsibility (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016). These views decrease the 3 scope of corporate citizenship and are thus not relevant to this research. The extended view of corporate citizenship highlights the ethical foundation of the concept with increased ethical expectations (Rendtorff, 2020) and a critical view of companies’ social role and the pressure from multiple stakeholders. This pressure refers to the external need for the company to behave ethically towards society and stakeholders and the internal need for companies to build an ethical and authentic company (Badenhorst-Weiss et al., 2016). Authenticity Dowling (2001) argues that employees anthropomorphise their companies, thus endowing the companies with humanlike qualities such as motives and intentions. Leaders are perceived as symbolic actors, epitomising the company, and their perceived authenticity, therefore, acts as a criterion to judge whether any citizenship activities such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) are authentic. If employees as stakeholders can endow humanlike qualities to their companies, so too can other stakeholders. Likewise, if companies are given humanlike qualities, stakeholders expect them to behave as authentic leaders (Kim et al., 2018). If something is considered authentic, it needs to be what it professes it to be. However, stakeholder expectations influence the evaluation of this authenticity as company activities, and communication is relative to these expectations. This means that a company may act and communicate in a way that achieves seemingly appropriate social and environmental impact, but is still deemed inauthentic by stakeholders causing reputational damage (Varga and Guignon, 2014). Stakeholders evaluate companies’ authenticity by considering how the company’s activities fit with a socially constructed norm about the appropriate actions. This is called iconic authenticity. Indexical authenticity is how the company’s activities or actions fit with its identity (Ewing, Allen and Ewing, 2012), also referred to as emblematic authenticity or identitybased authenticity, which is the perceived relation between an action and the stakeholder’s perception of the company’s identity (Grayson and Martinec, 2004). Skilton and Purdy (2017) introduced the concept of observed identity, which is a set of attributes that an observer (stakeholder) believes are central to and enduring about a company. This means that different observers (stakeholders) see different attributes as consistent with and emblematic of the company’s observed identity. This is particularly relevant to this study as the relationship between a company and its stakeholders is formed through a series of encounters, both past, current and future (Ashcroft et al., 2016), and what the company authentically communicates influences how they cultivate the relationship with a particular stakeholder (Holtzhausen and Zerfass, 2015). Authenticity is conceptualised as comprising four factors: self-awareness, an internalised moral perspective, relational transparency, and balanced information- 4 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 processing (Kim et al., 2018). In this context, selfawareness refers to the extent to which a company (as represented by its leader and members or employees) is aware of its values, philosophy, outlook on the world, its strengths and weaknesses, others’ evaluation of it and the company’s impact on others (Kernis, 2003; Kernis and Goldman, 2006; Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing and Peterson, 2008). The internalised moral perspective refers to whether a company has ethical and moral standards, formed by making decisions that develop selfawareness and behaving consistently with these ethical and moral standards (Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May and Walumbwa, 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2008). Relational transparency and balanced information processes are ways of conveying authenticity. Relational transparency refers to the extent to which a company consistently behaves in line with its authentic self (Kernis and Goldman, 2008; Walumbwa et al., 2008). Therefore, it also refers to the company’s ability to express thoughts and emotions and reliably provide information. Balanced information processes refer to a company’s ability to analyse related information before a decision is made objectively (Gardner et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2018). These factors are evident in the manner in which authentic leaders behave towards stakeholders. This refers to displaying qualities such as openness and clarity when sharing necessary information, accepting input from others and demonstrating their values, motives and sentiments. Cumulatively, these qualities enable stakeholders to assess the competence and morality of the leader. Through anthropomorphisation, these leaders’ behaviour effectively becomes the company’s behaviour, resulting in what may be regarded as an authentic company. In 2019, ACCA released a report entitled ‘Insights into integrated reporting 3.0: The drive for authenticity’, which highlighted that authenticity is demonstrated by the way companies reflect on how they create value over time and adhere to the IIRC’s integrated reporting (IR) framework. The IIRC was established as a coalition of regulators, investors, companies, standard setters, the accounting profession and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), with the view that communication concerning value creation is imperative for corporate reporting. Communication concerning value creation is embedded in integrated thinking, which refers to the company’s active consideration of the relationships between its various affected stakeholders (IIRC, 2013). The IIRC established the IR framework on which countries may base their reporting efforts. The IR framework indicates that a company’s authenticity will be enhanced if it follows the guiding principles of the framework. These principles include having a strategic focus which is future-orientated, considering the connectivity of information, providing insight into the company’s stakeholder relationships, disclosing information about matters that substantively affect the company, ensuring the report is concise, including all matters in a balanced way and presenting the information in a manner that is consistent over time and is material to its own ability to create value over time (King, 2018). These principles closely align with the factors of authenticity. Authentic stakeholder relationships A relationship exists between a person and a company in which there is a series of encounters with each other through actions and communication, shaped by the memory of past encounters and an imagination of future encounters. In these relationships, those involved are known to each other (or knowable), and the actions of each can affect another in a shared context or motivation. Stakeholder relationships are not a mere add-on to a company’s functioning, and require deliberate changes to how the company views and responds to issues. Company processes involved in decision-making are not normally designed to bring relational issues to the fore. Pressure, both in terms of time and as structural constraints, prevents the building of strong relationships with stakeholders. When companies are intentional about relationship-building, they create the perception of being known and valued (Ashcroft et al., 2016). To do this, the ethical principle of respect for integrity is essential. This integrity is expressed through trust, honesty and moral identity (Rendtorff, 2020). Stakeholders and companies are not stakeholders to each other, but stakeholders in specific issues of mutual interests (Saffer, 2019). The leadership of a company should be actively involved in the management of issues (Acros, 2013). However, issues cannot be seen in isolation and always involve an actor or stakeholder that affects the issue or is affected by it (Freeman, 1984). A shift has been made from a company-centric perspective of the roles and economic dependency of stakeholders, towards the mutuality of influence and impact in stakeholder relationships (Civera and Freeman, 2019). Stakeholder dialogue through engagement is needed to facilitate the mutuality of influence of stakeholders and companies (Golob and Podnar, 2014). Stakeholder engagement Stakeholder engagement is a process of positive stakeholder involvement and the basis for building a stakeholderoriented relational approach, which is necessary for value creation (Strand and Freeman, 2015). Greenwood (2007) argues that the more committed companies are towards their stakeholders, the more accountable and responsible they are, making them good corporate citizens. Civera, De Colle and Casalenga (2019) state that there are two types of engagement. The first is engagement with stakeholders in which stakeholders’ interests have an intrinsic value that is embedded in the company’s core decisions. The second is engagement of stakeholders in which stakeholders feel highly and positively committed to the company and aligned with its values and purpose. Authentic engagement is needed to enable engagement with and of stakeholders. Freeman and Velamuri (2006) highlighted that Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 stakeholders consist of real people with names and faces and children, and intensive communication and dialogue with stakeholders are needed. There are two levels of authentic engagement, namely authentically engaging the self, and authentically engaging others. Authentic engagement at all levels helps companies live out their values (self-awareness) (Kim et al., 2018) and similarly seek relationships with stakeholders with comparable characteristics. Personal and company approaches to diversity affect how authentic engagement is enacted. Authentic engagement with others means that the concepts of interconnection and inclusivity need to be explored (relational transparency) (Kim et al., 2018). This exploration starts with ‘inclusion as the normative process through which people who are socially marginalised and discriminated against are actively and intentionally brought into companies as full participants with voice and equal access to all benefits of membership’ (Antonio, Doehring and Hernandez, 2014: 60). Instead of traditional stakeholder management approaches, cultivation strategies targeted at stakeholder relationships may assist in facilitating authentic engagement. Cultivation strategies Positive stakeholder involvement through engagement strategies creates an antecedent for cultivating stakeholder relationships (Civera and Freeman, 2019). Kim and Hon (2009) developed six cultivation strategies, namely access, positivity, openness, sharing of tasks, networking and assurances. To determine which of these strategies (not limited to one) a company is using, it is necessary to determine the degree of effort that a company invests in providing a variety of communication or media platforms to assist stakeholders in making contact with it (namely access, or what may be regarded as engagement channels). Dawkins (2014) refers to this strategy as creating a favourable environment for stakeholders to express their needs and voices. The degree to which stakeholders benefit from the company’s efforts to make the relationship more enjoyable for stakeholders is referred to as positivity. Van Buren (2001) considers this positivity as obtaining stakeholder consent and trust. The company’s efforts to share in working on projects or solving problems of mutual interest with stakeholders (sharing of tasks) is demonstrated when a company adopts a collaborative mentality (Strand and Freeman, 2015). Openness refers to a company’s efforts to provide information about the nature of the company and what it is doing to establish fairer relationships (Phillips, 1997). The degree of the company’s effort to build networks with the same group of stakeholders such as activists (networking) is related to the company’s empowerment of more vulnerable and key stakeholders to favour the individual stakeholder’s contribution to the company (Civera et al., 2019). Any efforts by a company to assure its stakeholders that they and their concerns are attended to, are referred to as assurances (Holtzhausen and Zerfass, 2015). 5 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The research was approached from an interpretivist, naturalistic paradigm as the focus was on interpreting the text (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) associated with authenticity and cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships in the integrated reports of selected companies. To the knowledge of the author, no research has been conducted on how companies report on their approaches to stakeholder relationships and to cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships in their integrated reports. Therefore, an exploratory and qualitative design was adopted to gain new insights into this phenomenon (McLeod, 2015). In line with the guiding principles of the IR framework developed by the IIRC, an integrated report should, among others, provide insight into the nature and quality of the company’s relationships with key stakeholders and disclose information about matters that substantively affect the company’s ability to create sustained value (King, 2018). Therefore, the integrated report is the ideal publicly available communication vehicle in which companies are obliged to illustrate how they are cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships. In the integrated report, stakeholders get a sense of the authenticity of the company through what its leaders are communicating. Population and sampling The population of the study included all JSE-listed companies in South Africa that produced an integrated report while the sample was chosen using non-probability purposive sampling. The integrated reports included in this research comprised all the winners and merit award recipients in each of the categories of the Chartered Governance Institute of Southern Africa’s Integrated Report Awards of 2019 (Chartered Governance Institute of South Africa, n.d). It was compulsory that the companies were JSE-listed (JSE, n.d), and state-owned companies, the public sector, and NGOs or non-profit organisations (NPOs) were not considered. A total of nine winners and merit award recipients existed and all were included in the research. Research instrument and data collection The following framework was used to assess the integrated reports through directed content analysis. The construction of the framework was informed by the literature review. The 2019 integrated reports of the companies selected for inclusion in the research were downloaded from the Internet. No supplementary documents or documents referred to in the integrated reports were considered in the analysis. All information included in the research are in the public domain with no ethical implications for the research. 6 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 TABLE 1 KEY CONCEPTS AS INITIAL CODING CATEGORIES Conceptual component Authenticity (Kim et al., 2018) Evidence of: Self-awareness (how aware is a company of its values, philosophy, outlook, strengths and weaknesses, including the evaluation of and impact of others?). Focus on governance, citizenship, King IV. Internalised moral perspective (a company’s ethical and moral standards linked to sustainability, licence to operate, social justice). Relational transparency (the extent to which a company behaves in accordance with its values and principles, and its ability to express thoughts and emotions and provide information in a reliable and responsive way). Responsiveness. Balanced information process (a company’s ability to objectively analyse related information before a decision is made). Authentic stakeholder relationships (Ashcroft et al., 2016) Intentional relationship-building efforts, not a mere add-on. Structural openness and inclusion (authentic engagement) (Antonio et al., 2014). Issues management (Acros, 2015). Emerging issues. Access/engagement/channels (the effort that a company invests into providing a variety of communication or media platforms to assist stakeholders in making contact). Stakeholder identification and the stakeholder groups the company focussed on. Cultivation strategies (Kim and Hon, 2009) Positivity (which stakeholders benefit from the company’s efforts to make the relationship more enjoyable for stakeholders?). Sharing of tasks (the company’s efforts to share in working on projects or solving problems of mutual interest with stakeholders). Openness (a company’s efforts to provide information about the nature of the company and what it is doing). Networking (the company’s efforts to build networks with the same group of stakeholders such as activists). Consultation. Assurances (a company’s capacity to assure its stakeholders that they and their concerns are attended to [needs]). Analysis A combination of quantitative and qualitative content analysis was applied to the data as it focusses on the characteristics of language as communication, paying attention to the content or contextual meaning of text (typically found in integrated reports). With content analysis, both the explicit and implicit meanings of text are considered. The directed approach to content analysis of the data was guided by a structured process using the concepts from Table 1 that emerged from the literature review (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). The directed approach was adopted as the research extended existing theory and research on authenticity and cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships as a means to improve corporate citizenship. The main advantage of this approach is that existing theory can be supported and extended. However, the challenges to the naturalistic paradigm are that the data were approached with some bias related to the design of the study, the data collection and analysis. To curb these possible biases, the researcher was sensitive to and conscious of the possibility of multiple interpretations of especially the implicit meanings of the text. These were also addressed by applying rigour to the study. The Atlas Ti Version 8.4.25 software package was used to assist with the analysis. In Atlas Ti, content analysis techniques were applied to the data. The initial coding categories from Table 1 were used and evidence from the integrated reports was sought using key words associated with each of the categories. The key words were identified by creating word clouds and word lists to identify whether the key ideas from Table 1 were in fact present in the integrated reports. As a coding rule, the key words were then used to code the text in the integrated reports, upon which open coding was applied to ensure that more implicit meanings in the reports were captured. Through open coding, additional subcategories associated with the categories from Table 1 were created and key words added, until no new key words associated with the categories were found. Redundant codes were then identified and removed. The categories were organised according to the main concepts of the authentic company, authentic stakeholder relationships and cultivation strategies. The key words used were: values, governance, citizenship, King IV, sustainability, licence to operate, social justice, responsiveness, transparency, balance, openness, inclusion, issues, emerging issues, engagement, stakeholder identification, stakeholder benefits, mutual interest, activists, consultation, stakeholder needs, employees, stakeholders, media, community, government, regulators, NGOs, contractors, suppliers, analysts, clients, customers, industry, investors, unions, civil society, society, academic institutions, political parties. Rigour The four-dimensions criteria (FDC) created by Lincoln and Guba (1986) were applied to this research. Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 Authenticity To maintain credibility, credible and reliable sources of data were selected. These included the integrated reports of companies listed on the JSE and companies that were award winners in the Chartered Governance Institute of Southern Africa’s Awards for Integrated Reporting. To ensure dependability, a rich description of the methods used was provided and an audit trail established using the Atlas Ti software package, to record the data analysis process. For confirmability, a reflexive journal was kept of the insights gained from reading the integrated reports. To ensure transferability, purposive sampling was used to ensure that the study could be replicated using a different sample with the same inclusion criteria. Data saturation was obtained during analysis. The four factors of authenticity, namely self-awareness, internalised moral perspective, relational transparency and balanced information processes were identified in the selected company’s integrated reports using key words and phrases associated with these factors. Three companies used the word ‘authentic’ in their integrated reports to describe their philosophy towards engagement with their stakeholders: Our philosophy is to engage authentically, openly and inclusively with our stakeholders, allowing us to better understand and benefit from their insights, concerns, and priorities, to seek areas of potential partnership, mitigate risks to the business, and create mutual trust and respect – Retailer 2 FINDINGS The integrated reports from nine JSE-listed companies who were winners or merit award recipients of the CGISA’s Awards for Integrated Reporting of 2019 were analysed. The length of these reports ranged from 78 to 178 pages. The companies selected included banks, retailers, a medical company, steel and wood manufacturers and mining companies. The findings are presented per key concept of authenticity, authentic stakeholder relationships and cultivations by presenting tables indicating the number of times a key word or phrase were coded to a category, followed by an interpretive discussion of each of the categories. Evidence of balanced information processes was found in the integrated reports (40.83 per cent of all the codes associated with authenticity). The leadership of the selected companies managed to show how they analysed information before making decisions and how stakeholders may have influenced these decisions. The medical services company mentioned that: …the integrated report gives us an opportunity to reflect on, and assess, the fundamentals of [our] value proposition to our stakeholders. Our ability to execute confidently on a bold and responsive strategy; TABLE 2 SUMMARY OF THE CODING ASSOCIATED WITH THE CATEGORIES OF AUTHENTICITY Coding of categories Company Balanced information process Gr = 334 n Bank 1 Gr = 830 Steel manufacturer Gr = 326 Mine 1 Gr = 543 Medical services Gr = 705 Mine 2 Gr = 917 Bank 2 Gr = 884 Retailer 1 Gr = 837 Retailer 2 Gr = 791 Wood manufacturer Gr = 616 Total 7 Internalised moral perspective Gr = 249 Relational transparency Gr = 41 Self-awareness Gr = 194 Total % n % n % n % n 8 9.3 45 52.33 8 9.30 25 29.07 86 11 30.56 11 30.56 3 8.33 11 30.56 36 70 65.42 17 15.89 13 12.15 7 6.54 107 61 55.96 28 25.69 2 1.83 18 16.51 109 24 27.91 56 65.12 1 1.16 5 5.81 86 3 4.00 45 60.00 4 5.33 23 30.67 75 32 45.71 16 22.86 4 5.71 18 25.71 70 22 25.00 30 34.09 4 4.54 32 36.36 88 103 63.98 1 0.62 2 1.24 55 34.16 161 334 40.83 249 30.44 41 5.01 194 23.72 818 Note: Groundedness (GR) of the code indicates its relevance to the dataset 8 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 the underlying health of our operations and financial position; and, the purpose and values that guide the daily work of everyone at [the medical services company] and our impact on society; are the cornerstones of this value proposition. This finding highlights the moral perspective of the selected companies, which was evident across all the companies (30.44 per cent of all the codes associated with authenticity). Companies described their values and ethical approach to business in the finest detail, including a section focussed on purpose, vision and values: Within its overarching values, the company has five cultural themes including responsibility, adaptability, openness and connectivity, diversity and ownership. – Mine 1 Although the selected companies were aware of their values, their philosophical outlook, as well as their strengths and weaknesses, and placed emphasis on evaluating their impact on others (23.72 per cent of all the codes associated with authenticity), there was also a strong focus on citizenship, governance and the King IV Report. The steel manufacturer noted: Good corporate citizenship, including the company’s positioning and efforts in promoting equality, preventing unfair discrimination and combatting corruption, the group’s contribution to the development of communities in which it operates or markets its products and the group’s record of sponsorships, donations and charitable giving. This excerpt indicates an awareness and understanding of what it means to be a good corporate citizen and highlights its self-awareness of its values and impact on others. However, this awareness and understanding needs to be conveyed through relational transparency. Relational transparency is the way in which the leadership of a company express themselves and provide information in a reliable way, while also allowing stakeholders to freely express their views. This was evident in only 41 instances in the integrated reports, which raises concerns over the ability of companies to listen to and allow for the free expression of stakeholder viewpoints. The mining company (Mine 1) was the exception to this, dedicating six pages of its integrated report to stakeholder management. They describe what they call their key account management (KAM) approach as follows: It is a purpose-driven process that supports [our] stakeholder excellence objectives, our company’s purpose and our culture themes of ‘ownership’ (resultsorientated, efficient and effective) and ‘open and connected’ (collaborative, connected to the ecosystem). Authentic stakeholder relationships For stakeholder relationships to be authentic, the company’s intentions need to be clear and inclusive. This is only possible if the company’s structures and processes allow for this inclusivity, while considering that stakeholders are all connected through the issues that affect them. These attributes were explored in the integrated reports of the selected companies. While evidence for most of these qualities was found, it was difficult to ascertain from these reports whether structural openness was present. Issues and the management thereof were strongly represented in the texts of the integrated reports (57.22 per cent of the codes), indicating a cognisance of the importance of issues management in stakeholder relationships. Mine 1 outlined the issues (material matters), the stakeholders and its importance to both the mine and the stakeholders in a comprehensive, but compact way. However, for some companies, more focus was placed on how these issues may affect the company alone. This was demonstrated by Retailer 1 in the following statement: Material issues are the factors that are likely to have the most material impact on the Group’s revenue and profitability, and therefore influence our ability to create and sustain value for stakeholders. This clearly indicates that in this instance, the focus is first on revenue and profitability, followed by stakeholder value. In general, companies were quite intentional in their relationship-building efforts (35.04 per cent of the codes), demonstrating a recognition of the importance of stakeholder relationships. The steel manufacturer noted: Stakeholder engagement is based on the recognition that what we do has an impact on others. We need to understand what these impacts are (good or bad) and manage them responsibly, taking other people’s rights and priorities into account. This not only highlights the company’s intention to build relationships, but also addresses its moral and ethical awareness. Unfortunately, not much evidence was available of the companies’ efforts to be inclusive, with only 6.62 per cent of the codes making mention of inclusivity. If authentic stakeholder relationships are about companies understanding their own authenticity, their intentional relationship-building efforts and their ability to be inclusive in the process (Antonio et al., 2014), then the lack of a focus on inclusivity in their integrated reports is concerning. Cultivation strategies Access, assurances and networking were found to a greater or lesser extent in all the selected companies, while openness, positivity and the sharing of tasks were only identified in some companies. Regarding cultivation strategies, access was used the most (58.94 per cent of the codes related to cultivation strategies), and was the most prominent strategy in seven of the nine companies. This strategy involves the effort that a company makes in providing various Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 TABLE 3 SUMMARY OF THE CODING ASSOCIATED WITH THE CATEGORIES OF AUTHENTIC STAKEHOLDER RELATIONSHIPS Coding of categories Inclusion Gr = 71 Company Bank 1 Gr = 830 Steel manufacturer Gr = 326 Mine 1 Gr = 543 Medical services Gr = 705 Mine 2 Gr = 917 Bank 2 Gr = 884 Retailer 1 Gr = 837 Retailer 2 Gr = 791 Wood manufacturer Gr = 616 Total Intentional relationship-building efforts Gr = 376 n % n % 9 12.16 50 67.57 2 11.11 10 2 8.33 13 Issues management Gr = 614 Structural openness Gr = 12 Total % n % 11 14.87 4 5.40 74 55.56 5 27.78 1 5.56 18 4 16.67 16 66.67 2 8.33 24 14.77 64 72.73 9 10.23 2 2.27 88 16 5.71 66 23.57 196 70.00 2 0.71 280 7 3.87 38 20.99 136 75.14 0 0.00 181 11 4.53 60 24.69 171 70.37 1 0.41 243 10 8.77 61 53.51 43 37.72 0 0.00 114 1 1.96 23 45.10 27 52.94 0 0.00 51 71 6.62 376 35.04 614 57.22 12 1.12 1 073 n Note: Groundedness (GR) of the code indicates its relevance to the dataset EXTRACT 1 EXAMPLE FROM MINE 1’s INTEGRATED REPORT n 9 10 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 Networking (5.59 per cent of the codes), openness (2.14 per cent of the codes), positivity (2.46 per cent of the codes), and the sharing of tasks (1.36 per cent) were used to some extent. Although networking was not used extensively, it was used in all of the companies. The reason for this practice may be that it was used in specific instances that required this strategy. The steel manufacturer’s chairperson noted: communication and media platforms to help stakeholders engage with the company (Kim and Hon, 2009). Examples included digital platforms, electronic and social media, meetings, roadshows and reports, among others. This was demonstrated by Retailers 1 and 2, who indicated the following: Issues which are material to our customers are identified through daily interactions in our physical stores and our digital and social media platforms. Customer focus groups and surveys provide clear input to identify their requirements, interests, and concerns. – Retailer 1 I honestly also believe that we are starting to engage in a much more meaningful way with those nongovernmental companies which are concerned with environmental justice and which consistently (and commendably) hold up a lens to the performance of industries such as ours. Multiple communication channels are available to address issues raised by employees. These include a facility to pose anonymous questions to the CEO, participation in staff satisfaction surveys, employee roadshows, results presentations, in-store broadcasts, digital communications and employment equity forums. – Retailer 2 One company mentioned what they had learned from a networking engagement, which illustrates how useful the appropriate cultivation strategy is towards building authentic stakeholder relationships: Assurances were also utilised, and featured as the most favoured strategy of two of the nine companies (28.51 per cent of the codes). This is reassuring as it indicates that companies thus made efforts to ensure that their stakeholder needs and concerns are attended to (Holtzhausen and Zerfass, 2015). Bank 2 noted: Communication and lack of information were highlighted as areas of concern by the wage employees. – Wood manufacturer Openness was not mentioned that often, which may be explained by the fact that the integrated report itself is a representation of openness; sharing detailed information about the company with all interested parties. Some companies, however, did make specific mention of openness, such as the medical services company that had Our brand reflects the value created from being close enough to our clients to understand their needs and agile in developing solutions. TABLE 4 SUMMARY OF THE CODING ASSOCIATED WITH THE CATEGORIES OF CULTIVATION STRATEGIES Coding of categories Company Bank 1 Gr = 830 Steel manufacturer Gr = 326 Mine 1 Gr = 543 Medical services Gr = 705 Mine 2 Gr = 917 Bank 2 Gr = 884 Retailer 1 Gr = 837 Retailer 2 Gr = 791 Wood manufacturer Gr = 616 Total Access/ engagement / channels Gr = 432 Assurances Gr = 209 Networking Gr = 41 Openness Gr = 23 Positivity Gr = 18 Sharing of tasks Gr = 10 Total n % n % n % n % n % n % n 21 28.77 40 54.80 2 2.74 1 1.37 6 8.22 3 4.11 73 29 64.44 9 20.00 5 11.11 2 4.44 0 0.00 0 0.00 45 66 66.67 21 21.21 6 6.06 4 4.04 2 2.02 0 0.00 99 64 62.14 31 30.10 5 4.85 1 0.97 1 0.97 1 0.97 103 81 86.17 3 3.19 5 5.32 2 2.13 2 2.13 1 1.06 94 42 55.26 31 40.79 3 3.95 0 0.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 76 43 61.43 14 20.00 5 7.14 3 4.29 4 5.71 1 1.43 70 56 60.22 24 25.81 4 4.30 6 6.45 2 2.15 1 1.08 93 30 37.50 36 45.00 6 7.50 4 5.00 1 1.25 3 3.75 80 432 58.94 209 28.51 41 5.59 23 3.14 18 2.46 10 1.36 733 Note: Groundedness (GR) of the code indicates its relevance to the dataset Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 the following statement as one of their pillars underpinning their consistency of care strategy: Driving a culture of openness and collaboration. Positivity was difficult to identify as evidence to establish the degree to which stakeholders benefit from what the company does to make the relationship more enjoyable (Kim and Hon, 2009) was not contained in the integrated reports. While the companies did report on positivity, they did not do so extensively. Bank 1 reported that they were improving and leading client satisfaction metrics in industry. Similarly, evidence for the sharing of tasks was difficult to locate in the integrated report. Only 10 instances across all the integrated reports were found. The wood manufacturer noted: The company views its partnership within its surrounding communities as critical to the success of its operations. We believe that, with the combination of resources available, we can achieve and improve more than by operating in isolation. Through ongoing community engagement and consultation in various forums a sense of ownership is created around the well-being of the community and the success of the company. These communities are our prospective employees and the company will therefore continue to support, upskill and develop community members. Six companies used all of the strategies available. The use of the strategies depended on the nature of the stakeholder and relationship that existed between the stakeholder and the company. For example, one company used a digital platform to communicate with clients, and employed the sharing of tasks strategy when engaging with communities. The relationship between authenticity, authentic stakeholder relationships and cultivation strategies The text coded to the three broad concepts of the authentic company, authentic stakeholder relationships and cultivation strategies and their subcodes are presented in Digraph 1. The digraph also illustrates whether they are linked with one another by associations or by being part of a broader concept. The letters G and D appear in each of the code blocks. G refers to the groundedness of the code, that is, how relevant the code is to the dataset, while D refers to density, that is, how many codes are linked to another code. Access/ engagement/channels, intentional relationship-building efforts, balanced information processes, internalised moral perspective, corporate governance, sustainability focus and issues management all have a groundedness score above 200. These codes are thus relevant to the dataset. Relational transparency is the only code with a density score above 10 as many codes are linked to it. From the digraph it is evident that relational transparency is central to the company being authentic, to the 11 stakeholder relationships being authentic and to the cultivation strategies used. This finding has implications for a company’s stakeholder network as each element of cultivating authentic stakeholder relationships is influenced by a company’s relational transparency. This means that the extent to which a company behaves and expresses itself reliably and consistently influences whether and how a stakeholder experiences the relationship. Relational transparency is, therefore, the most important component of authenticity in this context. Evidence of relational transparency was scarce in Table 2, however, indicating that although this is central to building authentic stakeholder relationships, companies are unsure of how to convey their authenticity in their integrated reports. Internalised moral perspective and self-awareness are only connected to authenticity, implying that these two factors, although important, are only linked to authentic stakeholder relationships and cultivation strategies through relational transparency and balanced information processes. This means that authenticity consists of an inward-focussed component (internalised moral perspective and self-awareness) and an outwardfocussed component consisting of relational transparency and balanced information processes. The latter two refer to instances in which stakeholders interface with the company through the various cultivation strategies as well as relationship-building efforts, which are intentional and not merely an add-on to business practices. Openness is the one area in Digraph 1 that is linked to relational transparency, authentic stakeholder relationships (through inclusion) and cultivation strategies. However, limited evidence from the integrated reports was found to support the idea that the companies are open to or support openness, as seen in Table 3 (structural openness) and Table 4 (openness as cultivation strategy). This highlights not only the importance of openness when engaging with stakeholders, but also of inclusivity. DISCUSSION Stakeholders endow companies with humanlike qualities, expecting them to behave like authentic leaders would behave (Kim et al., 2018). Such behaviour is reflected in the relational transparency displayed by the company and through the extent to which the company is able to act consistently in line with its values, as well as its ethical and moral standards (Kernis and Goldman, 2008). South African companies do not place enough emphasis on their relational transparency, although this is the one area that has the most influence on the company’s ability to engage with its stakeholders authentically. A company that understands its own moral perspective has the ability to express this outwardly through relational transparency, using balanced information processes objectively (Gardner et al., 2005). Stakeholders already distrust companies (Weibel et al., 2020) due to the corporate scandals persisting in the business environment, which is exacerbated when companies fail to communicate and illustrate their internal moral perspective. 12 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 DIGRAPH 1 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN AUTHENTICITY, AUTHENTIC STAKEHOLDER RELATIONSHIPS AND CULTIVATION STRATEGIES Notes: In the circles: P = Property of; R = Associated with; N = Cause of; G = Part of In the blocks: CSR = Corporate social responsibility; UN = United Nations; G = Groundedness; D = Density Authentic stakeholder relationships are characterised by clear company intentions to build relationships through inclusivity (Ashcroft et al., 2016). To ensure inclusivity, issues management is important, not only in terms of how it affects the company, but also how it affects the stakeholders involved (Saffer, 2019; Civera and Freeman, 2019). These relationships are dependent on the company’s authenticity, and are closely associated with relational transparency, and cultivation strategies through the enactment of authentic engagement. Reporting by South African companies on their inclusivity efforts is scant, although there is evidence of their intentions to build authentic relationships with their stakeholders. This raises concerns over their ability to cultivate authentic relationships if inclusivity is not pursued. The nature of authentic engagement involves interconnectedness and inclusivity, both of which are associated with relational transparency. This means that a company that values inclusivity and interconnectedness is able to show its authentic self in how it enacts relational transparency. The inability of South African companies to fully incorporate inclusivity in their intentional relationship-building efforts, results in them losing out on the opportunity to ensure complete authentic engagement with marginalised or vulnerable stakeholders. Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 South African companies are mindful about issues management, and in some cases go to great lengths to address issues with stakeholders. These issues bring stakeholders and companies together around their mutual interests (Saffer, 2019). In this way, both relational transparency and authentic stakeholder relationships are supported as there is active involvement from the leadership of the company (Acros, 2015). The benefit of managing issues is that stakeholders feel that their needs and expectations are considered by the company (Holtzhausen and Zerfass, 2015), ultimately affecting their levels of trust (ACCA, 2019). Companies mainly use a variety of communication and media platforms as a cultivation strategy as engagement channels help stakeholders to express their needs and expectations (referred to as access). The other cultivation strategies of assurances and networking require a more direct involvement of both the companies and stakeholders and are therefore not used that often. Consequently, there are implications for the ability of companies to build trust (Van Buren, 2001), to solve problems collaboratively (Strand and Freeman, 2015), to establish fairer relationships (Phillips, 1997), to empower more vulnerable 13 stakeholders (inclusivity) (Civera et al., 2019), and to assure stakeholders that their concerns are acknowledged and attended to (Holtzhausen and Zerfass, 2015). Trust is not built through the management of impressions, in which companies merely offer generic information on risk and opportunities affecting stakeholders (ACCA, 2019). Apart from access, other cultivation strategies are necessary for relational transparency to materialise using balanced information processes. A framework to understand the stakeholder relationship network of the authentic company is therefore proposed based on the literature review and on the findings of this study. The framework is presented in Figure 1. In Figure 1, the authentic company is one of the actors in a network of stakeholders. The authentic company is conceptualised as having two dimensions. The first of these dimensions is inward-focussed (two inner circles) with moral perspective and self-awareness as factors, and the second dimension is outward-focussed (two outer circles), with relational transparency and balanced information processes as factors. The circle representing relational transparency is the largest as it is critical in communicating FIGURE 1 THE AUTHENTIC COMPANY’S STAKEHOLDER RELATIONSHIP NETWORK FRAMEWORK 14 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 the moral perspective of the company with stakeholders through the various cultivation strategies. The outermost circle represents the authentic stakeholder relationships developed through the company’s intentional relationshipbuilding efforts, structural openness, inclusion and issues management. The stakeholders are in close proximity to each other, linked with arrows that point in both directions and are embedded in the authentic stakeholder relationship circle. The proposed framework illustrates that companies’ (stakeholders) authentic self is emergent, which they need to be aware of, and which they need to express. Through these expressions, relationships are formed and issues addressed using relationship cultivation strategies, which in turn influence the company’s authentic self. The interconnectedness between the stakeholders assists them in influencing each other within the stakeholder network, while also holding each other accountable to being fair, transparent and honest. This brings stakeholders closer to each other, and assists them to practice relational transparency, which cannot exist without their moral perspective and self-awareness. Companies that are cognisant of their role in the stakeholder network will have a greater understanding of how their authenticity influences their ability to be good corporate citizens. CONCLUSION Companies are expected to act as good corporate citizens, and are under increased pressure to add value to society. They are, however, failing to do so because of the large number of corporate scandals affecting societal and stakeholder trust. This is exacerbated by the fact that the efforts to curb these corporate scandals do not have the desired effect. One area of promise is that of the shifting viewpoints on authentic communication, which involves transparency, honesty, and inclusivity. To communicate authentically, however, a company needs to be authentic and build authentic stakeholder relationships. As integrated reports form an integral part of authentic communication, this research focussed specifically on this regulatory communication vehicle, by analysing the integrated reports of selected South African companies to gain insight into how they report on their authenticity and stakeholder relationship efforts. The analysis of the integrated reports revealed that relational transparency is the biggest contributor to company authenticity. Although companies need to have a strong internal moral perspective and an awareness of this, these need to become evident in the company’s behaviour and communication (relational transparency and balanced information processes). Companies therefore need to shift their focus from demonstrating intentional relationshipbuilding efforts to applying specific relationship-cultivation strategies in which their true self and their behaviour become evident to stakeholders. These strategies refer to those that go beyond merely providing information, but that require active engagement between the company and stakeholders, solving problems collaboratively and including more vulnerable stakeholders. The authentic company’s stakeholder relationship network framework offers a bird’s eye view of a company’s position in a stakeholder network. Within this framework, the company is also a stakeholder in a network of stakeholders, in which each stakeholder requires authenticity in order for authentic relationships to form in the network. It also illustrates that stakeholders are connected through issues and with relational transparency. FUTURE RESEARCH The importance of this research is twofold. Firstly, applying the concept of authenticity to a company endowed by stakeholders with humanlike qualities provides for the opportunity to apply authentic leadership factors to the company. Leaders act on behalf of a company, while stakeholders develop feelings of trust towards the company itself. Further research is needed into the application of authenticity in a company and how authenticity manifests in the engagement companies have with stakeholders. Secondly, revealing the importance of relational transparency as the link between the authentic company and its stakeholders, highlights the contribution authentic stakeholder relationships and engagement make towards companies behaving as good corporate citizens. More research is needed into how relational transparency materialises from a stakeholder perspective, as this will provide much-needed insight into the proposed authentic company stakeholder relationship network framework. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS It is recommended that companies take cognisance of authenticity and how it influences its relationships and communication with stakeholders. Companies should do more to move from merely creating platforms for stakeholders to engage with them, towards actively involving and placing more emphasis on inclusivity. Using the authentic company’s stakeholder relationship network framework to guide discussion on the company, its authentic self and its role in a network of stakeholders, will assist companies in realising their potential in becoming good corporate citizens. REFERENCES Abratt, R. and Penman, N. 2002. Understanding factors affecting salespeople’s perceptions of ethical behaviour in South Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(4): 269–80. ACCA. 2019. Corporate governance: A South African perspective (Online). Available: https://www.acca global.com/ca/en/student/exam-support-resources/ fundamentals-exams-study-resources/f4/technicalarticles/corporate-governance-a-south-africanperspective.html [Accessed: 18 November 2020]. Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 Ashcroft, J., Childs, R., Myers, A. and Schluter, M. 2016. The relational lens and In. The relational lens: Understanding, managing and measuring stakeholder relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Antonio, E., Arora, K., Doehring, C. and Hernandez, A. 2014. Theological education and economic revitalisation: Creating sustainable companies through authentic engagement. Theological Education, 48(2): 57–67. Badenhorst-Weiss, H., Bimha, A., Chodokufa, K., Cohen, T., Cronje, L., Eccles, N., Grobler, A., Le Roux, C., Rudansky-Kloppers, S. and Botha, T. 2016. Corporate citizenship. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. Available: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true& AuthType=sso&db=nlebk&AN=1588756&site=edslive&scope=site [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. Black Sun. 2018. Less perfection, more authenticity: Analysis of FTSE 100 Corporate reporting trends in 2018 (Online). Available: https://www.blacksunplc. com/en/black-sun-live/company-news/2018/Lessperfection-and-more-authenticity-needed-in-FTSE100-annual-reports.html [Accessed: 25 April 2019]. Business Insider. 2020. The biggest South African business scandals over the last decade (Online). Available: https://www.businessinsider.co.za/the-top-southafrican-business-scandals-the-past-decade-2020-1 [Accessed: 18 November 2020]. Changing Our World, Inc. 2018. Changing our world corporate citizenship study (Online). Available: https:// changingourworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ The-Authenticity-Opportunity_PDF-for-Posting-orEmail.pdf [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. Chartered Governance Institute of South Africa. n.d. Integrated Report Awards 2019. The benchmark for integrated reporting (Online). Available: https://www. chartsec.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view =article&id=723&Itemid=268 [Accessed: 19 November 2020] Civera, C., De Colle, S. and Casalegno, C. 2019. Stakeholder engagement through empowerment: The case of coffee farmers. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(2): 156–174. Civera, C. and Freeman, R.E. 2019. Stakeholder relationships and responsibilities: A new perspective. Symphonya Emerging Issues in Management, 1: 40–58. Dawkins, C.E. 2014. The principle of good faith: Toward substantive stakeholder engagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(2): 283–295. De Jongh, D. 2004. A stakeholder perspective on managing social risk in South Africa. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 15 (Autumn 2004): 27–31. Delmas, M. and Burbano, C.V. 2011. The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1): 64–87. 15 Dowling, G.R. 2001. Creating corporate reputations: Identity, image and performance. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. Ewing, D.R., Allen, C.T. and Ewing, R.L. 2012. Authenticity as meaning validation: An empirical investigation of iconic and indexical cues in a context of ‘green’ products. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 11(5): 381–390. Flores-Araoz, M. 2011. Corporate social responsibility in South Africa: More than a nice intention. Polity. (Online). Available: http://www.polity.org.za/article/corporatesocial-responsibility-in-south-africa-more-than-a-niceintention-2011-09-12 [Accessed: 19 August 2018]. Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Massachusetts: Pitman Publishing. Freeman, R.E. and Mcvea, J.F. 2001. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract= 263511 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.263511 [Accessed: 22 March 2021]. Freeman, R.E. and Velamuri, S.R. 2006. A new approach to CSR: Company stakeholder responsibility. In Kakabadse, A. and Morsing, M. (Eds). Corporate social responsibility. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Gardner, W.L., Avolio, B.J., Luthans, F., May, D.R. and Walumbwa, F. 2005. ‘Can you see the real me?’ A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadership Quarterly, 16: 343–372. Golob, U. and Podnar, K. 2014. Critical points of CSR-related stakeholder dialogue in practice. Business Ethics: A European Review, 23(3): 248–257. Grayson, K. and Martinec, R. 2004. Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. Journal of ConsumerResearch, 31(2): 296–312. Greenwood, M. 2007. Stakeholder engagement: Beyond the myth of corporate responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4): 315–327. Hewitt, A. 2020. Four ways corporations can achieve authentic social impact (Online). Available: https:// ssir.org/articles/entry/four_ways_corporations_can_ achieve_authentic_social_impact [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. Hoeffler, S., Bloom, P.N. and Keller, K.L. 2010. Understanding stakeholder responses to corporate citizenship initiatives: Managerial guidelines and research directions. American Marketing Association, 29(1): 78–88. Holtzhausen, D.R. and Zerfass, A. 2015. The Routledge handbook of strategic communication. New York, USA: Routledge. IIRC. 2013. Value creation background paper (Online). Available: https://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/ uploads/2013/08/Background-Paper-Value-Creation. pdf [Accessed: 19 November 2020]. 16 Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 Institute of Directors (IoD). 2009. The King Report on Governance (Online). Available: https://cdn/ymaws. com/www.iodsa.co.za/resource/collection/944450064F18-4335-B7FB-7F5A8B23FB2F/King_III_Code_ for_Governance_Principles_.pdf [Accessed: 26 August 2021]. Jeppesen, S., and Granerud, L. 2004. Does corporate social responsibility matter to SMEs? The case of South Africa. Paper presented at the Interdisciplinary CSR Research Conference. Nottingham, UK. [Accessed: 22–23 October 2004]. JSE. n.d. Find an equity issuer (Online). Available: https:// www.jse.co.za/current-companies/companies-andfinancial-instruments [Accessed: 20 November 2020]. Kernis, M.H. 2003. Toward a conceptualisation of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14(1): 1–26. Kernis, M.H. and Goldman, B.M. 2006. A multicomponent conceptualisation of authenticity: Theory and research. In Zanna, M.P. (Ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. Kim, E.J. and Hon, L. 2009. Testing the linkages among the company–public relationship and attitude and behavioural intentions. Journal of Public Relations Research, 19(1): 1–23. Kim, B., Nurunnabi, M., Kim, T. and Kim, T. 2018. Doing good is not enough, you should have been authentic: Company identification, authentic leadership and CSR. Sustainability, 10(2026): 1–16. King, M. 2016. KING IV Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa (Online). Available: https://www. adams.africa/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/King-IVReport.pdf [Accessed: 19 November 2020]. King, M. 2018. Preparing an integrated report: A starter’s guide (updated) (Online). Available: http://integrate dreportingsa.org/ircsa/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ IRC_Starters_Guide_20180820_12663_LN.pdf [Accessed: 19 November 2020]. Kruggel, A., Tiberius, V. and Fabro, M. 2020. Corporate citizenship: Structuring the research field. Sustainability, 12: 1–19. Lincoln Y.S. and Guba E.G. 1986. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(30): 73–84. Maignan, I., Ferrell, O.C. and Hult, G.T. 1999. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(4): 455–69. McLeod, J. 2015. Reading qualitative research. European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, 17(2): 194–205. Nooyi, I.K. and Govindarajan, V. 2020. Becoming a better corporate citizen (Online). Available: https://hbr.org/ 2020/03/becoming-a-better-corporate-citizen [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. Nyamakanga, R. and Diphoko, W. 2017. Corporate corruption unpacked: SA lost billions. Cape Times, 14 July (Online). Available: https://www.pressreader. com/south-africa/cape-times/20170714/2815522 90902588 [Accessed: 19 August 2018]. O’Conner, A. and Shumate, M. 2018. A multidimensional network approach to strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4): 399–416. Ogbodu, S.G. and Umoru, G.L. 2018. Imperatives of corporate governance on corporate citizenship in Nigeria. Annual Survey of International and Company Law, 23: 133. Phillips, R.A. 1997. Stakeholder theory and a principle of fairness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7: 51–66. Rendtorff, J.D. 2020. Corporate citizenship, stakeholder management and sustainable development goals (SDGs) in financial institutions and capital markets. Journal of Capital Market Studies, 4(1): 47–59. Rowley, T. 1997. Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy of Management Review, 22(4): 887–910. Roussouw, G.J. 1994. Business ethics in developing countries. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(1): 43–51. Roussouw, G.J. 1997. Business ethics in South Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(14): 1539–1547. Roussouw, G.J. 1998. Establishing moral business culture in newly formed democracies. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(14): 1563–71. Roussouw, G.J. 2000. Defining and understanding fraud: A South African case study. Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(4): 885–95. Saffer, A.J. 2019. Fostering social capital in an international multistakeholder issues network. Public Relations Review, 45: 282–296. Salvioni, D. and Astori, R. 2013. Sustainable development and global responsibility in corporate governance. Symphonya Emerging Issues in Management, 1: 38–52. Skilton, P.F. and Purdy, J.M. 2016. Authenticity, power and pluralism: A framework for understanding stakeholder evaluations of corporate social responsibility activities. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(1): 99–123. Stangis, D. and Smith, K.V. 2017. 21st century corporate citizenship : A practical guide to delivering value to society and your business. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited (Gale Virtual Reference Library). Available: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?dir ect=true&AuthType=sso&db=nlebk&AN=1423572& site=eds-live&scope=site [Accessed: 22 March 2021]. Strand, R. and Freeman, R. 2015. Scandinavian cooperative advantage: The theory and practice of stakeholder engagement in Scandinavia. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1): 65–85. Management Dynamics Volume 30 No 3, 2021 Sonnenberg, D., Reichardt, M. and Hamann, R. 2004. Sustainability reporting in South Africa: Findings from the first round of the JSE Socially Responsible Index. Paper presented at the Interdisciplinary CSR Research Conference, Nottingham, UK . [Accessed: 22–23 October 2004]. Soundararajan, V., Brown, J.A. and Wicks, A.C. 2016. An instrumental perspective of value creation through multistakeholder initiatives, Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1): 10598. Tepper, T. 2019. Four core attributes of authentic corporate citizenship (Online). Available: https://npengage. com/companies/attributes-of-authentic-corporatecitizenship/ [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. The Economist. 2017. The big companies caught up in South Africa’s ‘state capture’ scandal (Online). Available: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2017/12/09/ the-big-companies-caught-up-in-south-africas-statecapture-scandal [Accessed: 26 November 2020]. Van Buren, H. 2001. If fairness is the problem, is consent the solution? Integrating ISCT and stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 11(3): 481–499. Van Coppenhagen, V. and Naidoo, S. 2017. The South African King IV Report on Corporate Governance: Themes and variations (Online). Available: https:// www.ensafrica.com/news/The-South-African-KingIV-Report-on-Corporate-Governance-themes-and va riations?Id=2495&STitle=corporate%20commercial %20ENSight%20 [Accessed: 19 August 2018]. 17 Varga, S. and Guignon, C. 2014. Authenticity. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 edition). In Zalta, Edward N. (Ed.) (Online) Available: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/ authenticity/ [Accessed: 23 March 2021]. Visser, W. 2002. Sustainability reporting in South Africa. Corporate Environmental Strategy, 9(1): 79–85. Visser, W. 2005. Corporate citizenship in South Africa. A review of progress since Democracy. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 18: 29–38. Walumbwa, F.O., Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., Wernsing, T.S. and Peterson, S.J. 2008. Authentic leadership: Development and analysis of a multidimensional theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1): 89–126. Weibel, A., Sachs, S., Schafheitle, S.D. and Laude, D. 2020. Stakeholder distrust-the neglected construct in stakeholder relations (Online). Available: https://www. alexandria.unisg.ch/259644/ [Accessed: 26 November 2020]. Yang, A. and Bentley, J. 2017. A balance theory approach to stakeholder network and apology strategy. Public Relations Review, 43: 267–277. Yohn, D.L. 2020. Brand authenticity, employee experience and corporate citizenship priorities in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Strategy and Leadership, 48(5): 33–39. All correspondence should be addressed to: Dr Corné Meintjes, Department of Strategic Communication, University of Johannesburg, cmeintjes@uj.ac.za