Disclosure Preparation and Managers’ Explanations for Performance

advertisement

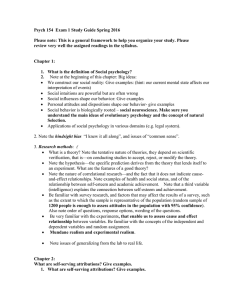

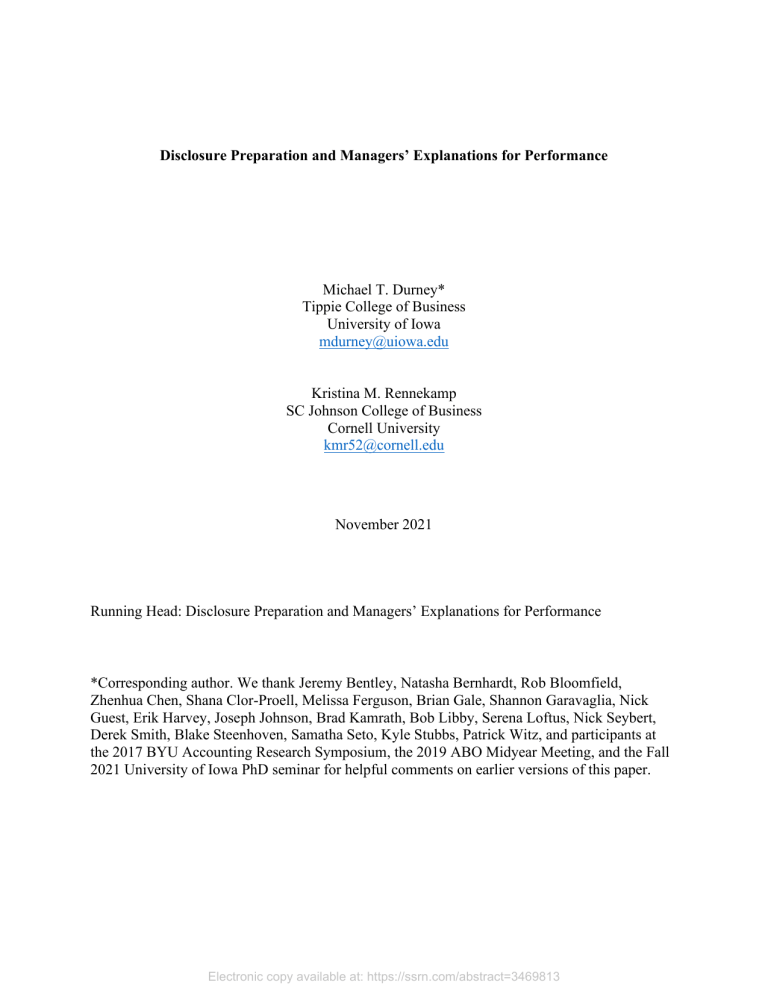

Disclosure Preparation and Managers’ Explanations for Performance Michael T. Durney* Tippie College of Business University of Iowa mdurney@uiowa.edu Kristina M. Rennekamp SC Johnson College of Business Cornell University kmr52@cornell.edu November 2021 Running Head: Disclosure Preparation and Managers’ Explanations for Performance *Corresponding author. We thank Jeremy Bentley, Natasha Bernhardt, Rob Bloomfield, Zhenhua Chen, Shana Clor-Proell, Melissa Ferguson, Brian Gale, Shannon Garavaglia, Nick Guest, Erik Harvey, Joseph Johnson, Brad Kamrath, Bob Libby, Serena Loftus, Nick Seybert, Derek Smith, Blake Steenhoven, Samatha Seto, Kyle Stubbs, Patrick Witz, and participants at the 2017 BYU Accounting Research Symposium, the 2019 ABO Midyear Meeting, and the Fall 2021 University of Iowa PhD seminar for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Disclosure Preparation and Managers’ Explanations for Performance ABSTRACT There is considerable variation across firms and settings in the level of advance preparation for disclosures. Differences in disclosure preparation result in different market outcomes, and less preparation results in greater cognitive load for managers when issuing disclosures. Yet, little is known about how greater cognitive load (i.e., lack of time, effort, or ability in disclosure preparation) affects disclosure characteristics. Using two experiments and a survey, we investigate how managers’ explanations for performance differ when issued under greater cognitive load. Our experiments vary cognitive load and task performance and solicit reports explaining the reasons for performance on abstract tasks. We find that participants provide more internal reasons for performance when responding under greater cognitive load following both good and poor performance. A follow-up survey of IROs documents reasons for different amounts of disclosure preparation, as well as potential consequences. Our results shed light on why managers invest in different levels of disclosure preparation and provide evidence on how cognitive load affects disclosure characteristics. Keywords: voluntary disclosure, spontaneity, causal attributions, private disclosure, cognitive load Data Availability: Contact the authors. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 1. Introduction Like investors, managers’ attention is limited (Hirshleifer and Teoh 2003; Land 2019), such that managers must allocate time between various activities, including making operational decisions, developing firm strategy, and preparing for disclosures. Managers prepare disclosures for public conference calls and private meetings with investors by writing scripts, compiling anticipated questions, rehearsing disclosures, and developing strategies to handle unanticipated questions (Lee 2016; Brown et al. 2019; Amel-Zadeh et al. 2019; Durney 2021). Yet, allocating time and resources to disclosure preparation is costly (Abenate 2018). While direct evidence is sparse regarding managers’ disclosure preparation behavior (AmelZadeh et al. 2019), several recent studies document variations in the extent of preparation among firms and across disclosure types. Brown et al. (2019) survey IROs about the importance of different preparation methods and find that IROs find the following strategies to be “very important”: scripting remarks (93 percent), preparing a list of anticipated questions and corresponding responses (82 percent), developing a strategy to handle unanticipated questions (60 percent), and conducting rehearsals for earnings conference calls (49 percent). Durney (2021) also surveys IROs and finds that the extent of scripting is greater for earnings conference calls than for private phone calls and face-to-face meetings with investors. Amel-Zadeh et al. (2019) gather field data to show “that there is considerable variation in who prepares disclosures, when they are prepared, and the amount of effort expended by different types of managers” and that this variation correlates with actual differences in the “structure, style, and tone of 10-Ks and conference calls.” In this study, we provide causal evidence on how differences in disclosure preparation might indirectly affect the explanations that firms provide for their performance by affecting managers’ cognitive load. Examining the effect of cognitive load on managers’ disclosures is important 1 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 because the extent of disclosure preparation varies, which has downstream consequences for managers’ cognitive load, but the corresponding effects on disclosure characteristics are not well understood. Our study fills a gap in the literature by investigating how managers’ disclosures change with cognitive load. We specifically examine how one disclosure characteristic differs: managers’ causal attributions; or, in other words, their explanations for performance. Understanding how disclosure preparation affects attributions for firm performance is important given the prior literature showing that managers’ causal attributions affect market reactions (cf. Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Kimbrough and Wang 2013) Our predictions draw on psychology research that indicates one’s natural tendency is to focus inwardly on oneself (Ross and Sicoly 1979; Gilovich et al. 2000; Savitsky et al. 2001; Epley et al. 2002; Gilovich et al. 2002). Ross and Sicoly (1979) argue that this inward focus is driven at least in part by more cognitively available information about oneself versus information about others and the external environment. People are thus initially anchored on their own experiences. Inclusion of external information in the attribution process involves effortful adjustment, which is more difficult under cognitive load (Gilovich et al. 2000; Savitsky et al. 2001; Epley et al. 2002; Gilovich et al. 2002). We therefore predict that cognitive load will lead managers to provide more internal attributions for performance. Our investigation helps resolve some conflicting results in psychology research on causal attributions by providing evidence that internal causal attributions occur more spontaneously than external causal attributions. We test our prediction and provide evidence on the issue with two experiments and a survey. Our first experiment uses a 2x2 between-participants design where participants report the reasons for performance on an abstract task. The experiment manipulates cognitive load as high or low and sorts participants into good or poor task performance conditions before soliciting free- 2 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 response performance reports. Experimental results confirm our predictions as we find that participants under greater cognitive load give more internal reasons for their performance following both good and poor performance. This suggests that managers are more likely to explain performance with an internal focus when they engage in less disclosure preparation and face greater cognitive load. Consistent with theory, supplemental analyses indicate the underlying psychological process is, at least in part, nonconscious. Our second experiment again manipulates cognitive load and complements the first experiment by ruling out an alternative explanation for results. Specifically, we rule out the possibility that cognitive load simply makes it more difficult for managers to provide accurate explanations for performance. Again, we find that participants under greater cognitive load give more internal reasons for their performance. Thus, greater cognitive load in our experiments prevents effortful adjustment needed to incorporate external information, resulting in performance reports that are internally focused. We complement the experiments with a survey of Investor Relations Officers (IROs), who are known as “chief disclosure officers” (Brown et al. 2019). We conduct the survey to connect our experiments with actual disclosure preparation by asking about (a) the reasons for, and (b) the consequences of, managers’ disclosure preparation. Results suggest that disclosure preparation (a) is motivated by a desire to reduce unfavorable disclosures and (b) reduces disclosures that contain inconsistent messaging and unfavorable information. Unfavorable disclosures in practice analogize to our experimental settings in the form of internal attributions for poor performance and external attributions for good performance, consistent with prior research (Barton and Mercer 2005; Kimbrough and Wang 2013). 3 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 We use the comparative advantages of experimental and survey research to complement the archival literature in this area. Although archival research has investigated managers’ explanations provided in firm disclosures, and market reactions to more versus less prepared disclosures, the underlying process of preparing these disclosures is unobservable in archival data. Our study provides evidence on the psychological process of disclosure preparation by examining the effect of cognitive load on performance explanations analogous to those provided in firm disclosures. As such, we provide one type of process evidence enumerated by Asay et al. (2021) – namely, we provide a better understanding of the process behind the cause-effect relationship of disclosure preparation on disclosure outcomes. Our study makes three contributions to the literature. First, in response to Bloomfield’s (2008) call for such research, we provide evidence on how differing levels of preparation might affect disclosure characteristics. We do this by showing that managers’ explanations for performance are more internally focused under more cognitive load, which maps to disclosure settings with less preparation. While research indicates that variation in disclosure preparation influences market outcomes (Lee 2016), little is known about how disclosure characteristics vary based on differing levels of disclosure preparation.1 Our evidence on how cognitive load affects disclosures also increases our understanding of the difference between public and private disclosures. Durney (2021) finds that private disclosures involve less preparation than public disclosures, suggesting that managers respond with more cognitive load in private settings, ceteris paribus. 1 Recent working papers by Rennekamp, Steenhoven, and White (2021) and Asay, Clor-Proell, and Durney (2021) offer some indirect evidence on the consequences of cognitive load for disclosures. Specifically, Rennekamp et al. (2021) examine how managers’ attempts to suppress emotion and avoid unintentionally revealing information (which increases cognitive load) affect investors’ perceptions of the manager. Asay et al. (2021) examine how IROs’ disclosure preparation (which decreases cognitive load) affects disclosure content in private meetings with investors. 4 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Second, we provide evidence on how and why managers prepare for disclosures. Evidence is lacking regarding managers’ disclosure preparation (Amel-Zadeh et al. 2019). Our experimental results suggest that disclosure preparation focused on explaining poor performance can avoid unfavorable outcomes. Specifically, we show that managers may be more likely to blame poor performance on themselves or the firm when explaining poor performance under more cognitive load. Disclosure preparation might prevent such disclosure of unfavorable information by devoting the cognitive resources necessary to incorporate external reasons for poor performance. We also place our experimental results in the context of IROs’ perceptions of the reasons for, and consequences of, disclosure preparation. IRO respondents in our survey indicate that disclosure preparation is motivated by a desire to reduce unfavorable disclosures. Combined with our experimental results, this evidence supports assumptions in Lee (2016) about why managers prepare for disclosures. Lee (2016) argues that his finding of less spontaneous disclosure following bad news is driven by a desire to reduce spontaneous disclosure of bad (vs. good) news, but he admits that he cannot rule out an alternative explanation that firms are simply better at anticipating investor questions with bad (versus good) news. Our experimental results support Lee’s (2016) assertions by providing causal evidence that more cognitive load results in unfavorable disclosures in the form of internal attributions for poor performance. Thus, more disclosure preparation, in line with IROs reasons for disclosure preparation from our survey and Lee’s (2016) assertions, can counteract the unfavorable disclosures resulting from increased cognitive load. Lastly, our findings contribute to the research on managers’ causal attributions, which documents the market impact of the attributions that managers provide (cf. Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Kimbrough and Wang 2013). The results of our paper suggest that 5 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 managers’ causal attributions may not always be intentional, contrary to the typical assumption in this literature (Staw et al. 1983; Salancik and Meindl 1984; Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Barton and Mercer 2005; Osma and Guillamón-Saorín 2011; Chen 2012; Elliott et al. 2012; Libby and Rennekamp 2012; Kimbrough and Wang 2013; Libby and Emett 2014; Chen et al. 2016). The assumption in this prior research that managers’ causal attributions are intentional may be due to the fact that prior research largely focuses on textual disclosures, which are more likely to contain strategic and intentional attributions due to the extent of preparation (AmelZadeh et al. 2019). However, other disclosure settings such as live interviews, earnings call Q&As, and private meetings with investors, in which managers frequently participate, are more susceptible to unintentional disclosures (Durney 2021). Our results speak to these other settings and indicate that managers’ explanations for performance may be driven, at least in part, by psychological processes outside managers’ awareness. Such unintentional disclosures provide at least a partial explanation for prior archival results that show managers sometimes issue internal attributions for poor performance despite contrary incentives (Lee et al. 2004; Chen 2012; Kimbrough and Wang 2013; Zhou 2014; Chance et al. 2015). The paper proceeds as follows. Section II reviews related literature and develops our hypotheses. Section III presents the experimental method and results for our first experiment. Section IV presents our second experiment, Section V presents the survey method and results, and Section VI concludes. 2. Background and Hypothesis In this section we develop our hypothesis with respect to how managers’ cognitive load might affect the causal attributions that they provide to explain firm performance, starting with a review of the broader literature on causal attributions. 6 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Causal Attributions Causal attribution research began with Heider (1944, 1958) theorizing that people tend to explain outcomes by attributing them to internal or external causes. On the level of the individual, internal attributions refer to causes attributable to oneself such as ability or effort and external attributions refer to environmental causes such as task difficulty or luck. In a corporate setting, internal attributions might attribute cause to management or the firm, and external attributions might attribute cause to the economy or the industry. An early review by Miller and Ross (1975) focuses on self-serving causal attributions. Selfserving attributions attribute the causes of good performance to internal factors and the causes of poor performance to external factors. In their review, Miller and Ross (1975) conclude that the early studies find that individuals make self-serving attributions following good but not poor performance (c.f., Schopler and Layton 1972; Beckman 1973; Wolosin et al. 1973). Duval and Silvia (2002) find similar asymmetric evidence in their review of the literature nearly 30 years later. More specifically, while researchers consistently find evidence of internal attributions after good performance, the evidence is mixed regarding poor performance, with some studies finding internal and some studies finding external attributions after poor performance (Duval and Silvia 2002). A meta-analysis supports these conclusions with consistently positive effects of good performance on self-serving attributions but both positive and negative effects of poor performance on self-serving attributions (Campbell and Sedikides 1999). Cross-cultural evidence exhibits similar patterns of results (Mezulis et al. 2004; Sakaki and Murayama 2013). Overall, prior research consistently finds internal attributions following good performance but either internal or external attributions following poor performance. 7 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 These conflicting results for attributions following poor performance might be partially explained by research on the effect of cognitive load on causal attributions, a literature where the evidence is still inconclusive (Sakaki and Murayama 2013). Responses issued under greater cognitive load are characterized by less effortful control and are consistent with more “automatic” responses investigated in the psychology literature (Bargh and Williams 2006). Research on other egocentric biases provides insight into what automatic causal attributions might look like. For example, Ross and Sicoly (1979) find that people overestimate their individual contributions to group endeavors that result in both positive and negative outcomes. The researchers argue that this occurs at least in part because information about the self is more cognitively available than information about others or the external environment (Ross and Sicoly 1979). Later research builds on this concept and shows that people anchor on information about themselves, and effortful adjustment is required to cognitively incorporate information about others and the external environment (Gilovich et al. 2000; Savitsky et al. 2001; Epley et al. 2002; Gilovich et al. 2002). While this prior research does not directly examine the effect of cognitive load on causal attributions, the results suggest that attributions issued under greater cognitive load will be more internally focused, regardless of prior performance, because internal reasons for performance are more easily available than external reasons. This research leads us to predict that managers under greater cognitive load will attribute performance internally, regardless of performance, because coming up with external attributions requires more effortful adjustment. Causal Attributions in Financial Reporting A stream of literature in accounting and finance leverages the aforementioned psychology research on individuals’ attributions about their own performance to make predictions about managers’ attributions for firm performance, and corresponding consequences. This literature 8 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 finds that managers’ narrative financial reports contain causal attributions that affect market outcomes and investor decisions. Stock market reactions vary with the amount and type of attributions for financial performance given by managers (Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Kimbrough and Wang 2013). Individual investors and analysts also exhibit different judgments and decisions based on whether managers attribute performance internally or externally (Barton and Mercer 2005; Elliott et al. 2012). Additionally, self-serving attributions may contribute to the issuance of earnings forecasts (Libby and Rennekamp 2012). The voluntary disclosure literature largely assumes that managers issue disclosures intentionally. A recent review notes that “prior literature reveals two fundamental perspectives regarding managers’ disclosure motives – the opportunistic perspective and the information perspective” (Libby and Emett 2014, p. 414), both of which are intentional. Similarly, most of the work on manager’s causal attributions assumes that managers’ causal attributions are intentional (Staw et al. 1983; Salancik and Meindl 1984; Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Barton and Mercer 2005; Osma and Guillamón-Saorín 2011; Chen 2012; Elliott et al. 2012; Libby and Rennekamp 2012; Kimbrough and Wang 2013; Chen et al. 2016). Yet, prior research suggests that causal attributions could be the result of unintentional (i.e., automatic) processes. In fact, Aerts (2005) argues that unintentional motivations drive differences in attributional patterns between listed and unlisted firms. More recently, Asay et al. (2018) find that experienced financial managers think they use causal language in financial reports differently than they actually do, indicating that managers may not always issue causal attributions intentionally. Since information for internal attributions is more readily available in individuals’ minds (Ross and Sicoly 1979), we predict that managers automatically attribute both good and poor 9 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 performance to internal causes. However, we expect managers to incorporate more external attributions when additional cognitive resources are available. Managers’ advance preparation for a disclosure affects the number of cognitive resources available in practice. With more advance preparation, responses to questions can be easily recalled during a disclosure because they may have already been considered. This reduces managers’ cognitive load during a disclosure and allows them to expend greater cognitive resources on answering unanticipated questions, or to provide richer information in their responses. On the other hand, a lack of preparation requires more effortful thinking, and leads to greater cognitive load because it reduces the cognitive resources available to managers. We therefore predict more internal attributions when managers are under greater cognitive load because cognitive load reduces the cognitive resources necessary to incorporate external attributions. HYPOTHESIS: Narrative performance reports will include more internal attributions with increased cognitive load. Our hypothesis is a main effect prediction of cognitive load on the extent of internal vs. external attributions. However, if the dependent variable is the extent of self-serving attributions, then our hypothesis suggests an interactive effect of cognitive load and performance on the extent of self-serving attributions. More specifically, our hypothesis implies that managers’ narrative performance reports will include more (less) self-serving attributions when managers are under increased cognitive load following good (poor) performance. Examining the extent of self-serving attributions in addition to the extent of internal or external attributions is important to better connect with the causal attribution research in the financial reporting and psychology literatures. In financial reporting, both the early (e.g., Staw et al. 1983; Bettman and Weitz 1983) and more recent (e.g., Kimbrough and Wang 2013; Zhou 2014) research maintains a focus on the self-serving nature of managers’ attributions. This focus 10 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 might be motivated by results showing the impact of managers’ self-serving attributions on stock price (Baginski et al. 2004). Likewise, in psychology, both the early (e.g., Heider 1958; Miller and Ross 1975; Miller 1976) and more recent research (e.g., Duval and Silvia 2002; Sakaki and Murayama 2013) focuses on the self-serving nature of causal attributions. One reason for the continued focus on self-serving attributions is the divergent findings regarding whether people actually attribute causes in a self-serving way following poor performance (Miller and Ross 1975; Duval and Silvia 2002). Our paper sheds light on automatic causal attributions in response to poor performance, which helps inform the discrepant findings regarding self-serving attributions in psychology. In fact, one reason why some studies find internal attributions and others find external attributions following poor performance could be due to differences across studies in the cognitive resources available to participants when making attributions. We test this directly in our experiment. 3. Experiment One Participants We recruit 138 MBA students at a highly ranked MBA program to participate in our experiment2 Participants average 28 years of age and 37 (27 percent) identify as female. We use MBA students to proxy for managers since we are examining a basic psychological mechanism with an abstract task. Thus, MBA students are an appropriate match to the goals of our experiment (Libby et al. 2002). Design and Overview We test our hypotheses using a 2x2 between-participants experiment that manipulates cognitive load (High or Low) and varies task performance (Good Performance versus Poor 2 Approval for this experiment was obtained from the University’s Institutional Review Board. 11 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Performance) on an abstract trivia-question task. Following prior work (Libby and Rennekamp 2012; Asay 2018), we design the task to capture key elements of managers’ financial reporting environment while holding constant confounding variables that prevent clean causal inferences. Specifically, our manipulation of cognitive load reflects differences in managers’ disclosure preparation. For example, more preparation prior to disclosure results in lower cognitive load. However, disclosure preparation and cognitive load, along with performance, are potentially confounded in practice with variables like ability, rendering a causal examination difficult. Additionally, our abstract task allows participants to feel involved with the actual performance in the task and provide corresponding attributions, which would not be possible with a more context-rich task that looks more like a management disclosure context one might find in practice. In our experiment, participants first answer seven difficult binary-choice trivia questions. Then, participants learn their score and that their performance is either better or worse than average depending on whether participants answered 4-7 (i.e., Good Performance) or 0-3 (i.e., Poor Performance) questions correctly. After that, we ask participants to remember an 8- or 1digit number corresponding to High or Low cognitive load, respectively. Finally, participants explain the reasons for their Good Performance or Poor Performance in a narrative freeresponse format, enter the 8- or 1-digit number they were asked to remember, and respond to post-experimental questions. Our main dependent variable is the locus of (i.e., extent of internal or external) causal attributions in participants’ narrative performance reports. Independent Variables We design our manipulation of cognitive load to reflect the extent of managers’ lack of time, effort, or ability in disclosure preparation in practice. Increased cognitive load in our experiment 12 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 should reduce participants’ available cognitive resources similar to how less preparation reduces managers’ available cognitive resources. To craft this manipulation, we follow psychology research in manipulating availability of cognitive resources. The specific operationalization of our manipulation involves giving participants an 8- or 1-digit number to memorize. This method is used in psychology research to examine more automatic psychological processes, which are evident under greater cognitive load (Gilbert and Silvera 1996; Van Dillen et al. 2013). Therefore, in our experiment we employ greater cognitive load (i.e., the 8-digit number) to examine the kind of causal attributions that managers issue more automatically. For our independent variable of task performance, we design seven trivia questions to sort participants into conditions of good and poor performance. While we do not randomly assign participants to performance conditions, we carefully structure the task to sort participants into performance conditions while minimizing any potential influence from knowledge, ability, effort, or other individual characteristics. Following prior literature (Libby and Rennekamp 2012; Asay 2018), we select questions from Trivial Pursuit (Hasbro 2009). We select 10 difficult questions, modify the questions to be binary-choice, and administer the questions as a pretest to 34 MBA students from the same participant pool as our main sample.3 Our goal is to retain questions where the correct response rate is no different from chance, in order to limit the likelihood that performance on the task is driven by differences in knowledge, ability, effort, or other individual characteristics. Results from this pretest reveal that responses to two of the questions significantly differ from chance (both p<0.050, two-tailed, untabulated). We drop these two questions and one additional question for which some participants indicate clear knowledge via post-experimental feedback. 3 None of the students that participated in the pre-testing of questions were participants in the main experiment. 13 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 With the final seven questions (shown in the Appendix), we examine the individual characteristics for pretest participants who perform well (i.e., answer 4-7 questions correctly) versus those who perform poorly (i.e., answer 0-3 questions correctly). While we do not perfectly measure knowledge, ability, and effort, we do measure level of education, work experience, age, and time spent on the trivia questions. Participants who perform well do not have significantly more education or work experience and are not significantly older than participants who perform poorly (all p > 0.400, two-tailed, untabulated). There are also no differences between those who perform well and those who perform poorly when it comes to perceptions of question difficulty, predicted accuracy, or time spent (all p > 0.250, two-tailed, untabulated). These results suggest that ability, knowledge, effort, and other individual characteristics do not affect task performance, on average. Our independent variable of task performance is especially important in understanding the psychology behind managers’ causal attributions. If we just examine instances of either good or poor performance, we could not distinguish between different process explanations. We predict cognitive load leads to more internal attributions because internal attributions are more readily available (Ross and Sicoly 1979). However, another explanation might be that cognitive load leads to increased motivational processes. For example, if we examined good performance alone, then it would be more difficult to argue that results are due to information availability (Ross and Sicoly 1979) compared to a motivational explanation to appear as a good performer. Dependent Variables To measure managers’ causal attributions, we ask participants to give the reasons for their performance in a free-response text box. Using a free-response question for our primary dependent variable allows us to better examine the psychological mechanism behind causal 14 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 attributions compared to using a scale that explicitly asks about internal/external attributions (Malle 2011a, 2011b; Böhm and Pfister 2015). Participants give reasons for their performance in the free-response text box after we tell them to memorize a number but before we ask them to recall the number. Blind to condition, two research assistants code participants’ performance reports by placing each report in one of three buckets: mostly internal reasons, mostly external reasons, or about the same amount of internal and external reasons. We assign ‘1’ to performance reports with mostly internal reasons, ‘-1’ to reports with mostly external reasons, and ‘0’ to the reports with about the same amount of internal and external reasons for performance. The coders agreed on all ratings, which comprise our primary dependent measure. For practical relevance and to connect with prior literature, we also examine the extent of self-serving versus self-disserving reasons for performance. Self-serving reasons are internal attributions for good performance and external attributions for poor performance, while selfdisserving reasons are external attributions for good performance and internal attributions for poor performance. Transforming our main dependent variable to show the extent of self-serving attributions involves multiplying the aforementioned coding for participant reports in the Poor Performance conditions by ‘-1’. By doing so, we assign ‘1’ to reports with mostly self-serving reasons for performance, ‘-1’ to performance reports with mostly self-disserving reasons, and ‘0’ to reports with about the same about of self-serving and self-disserving reasons for performance. Compensation We compensate participants in three ways. First, participants receive a flat $3 participation fee. Second, participants earn an additional $1 for each trivia question that is answered correctly. Lastly, we enter participants into a drawing for one of two $50 Amazon gift cards if they correctly remember the 1- or 8-digit number from our cognitive load manipulation. 15 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Manipulation Checks To check our manipulation of cognitive load, we examine participants’ recollection of the 1or 8-digit number. Most participants either remember the number exactly (72 percent) or at least make an obvious attempt at remembering the number (91 percent), indicating a successful manipulation of cognitive load. The remaining 9 percent of participants enter a number with a significantly different number of digits (e.g., a 3-digit or a 4-digit number). Dropping these participants strengthens our results, but we include all participants in all tests for completeness. To check our manipulation of task performance, we examine participants’ perceptions of their performance on the trivia question task using a 7-point scale with endpoints of 1=Very poorly and 7=Very well and a midpoint of 4 =Neither poorly nor well. Consistent with expectations, participants in the poor performance condition report feeling that they performed significantly worse than participants in the good performance condition (2.91 vs. 4.15, p < 0.001, one-tailed, untabulated).4 Hypothesis Tests Our hypothesis predicts a main effect of cognitive load such that managers give more internal reasons for performance when cognitive load is High versus Low, regardless of performance condition. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and tests of H1 and Figure 1 displays cell means. As shown in Table 1 panel B, the main effect of load in our ANOVA is significant (p < 0.001, one-tailed) in support of our hypothesis that managers tend to automatically attribute performance internally. Importantly, Figure 1 shows that the same patterns of results exist following both Good Performance and Poor Performance, supporting our theoretical argument 4 We are primarily interested in the difference in perceived performance across the performance conditions, but for completeness we also compare responses to the scale midpoint (4). The mean response of 2.91 (4.15) in the poor (good) performance condition is (not) significantly different from the midpoint with two-tailed p<.001 (p=0.295). 16 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 that these results can be explained by more cognitively available internal (vs. external) attributions. [INSERT TABLE 1 AND FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE] To connect with prior research in accounting and psychology, we also examine participants’ self-serving disclosures. As discussed in the previous section, this involves transforming the dependent variable for participants in the Poor Performance conditions by multiplying by ‘-1.’ This new measure shows the extent of self-serving attributions (internal reasons for Good Performance and external reasons for Poor Performance) in the performance reports. Our prediction in H1 implies that this new measure will show an interaction between cognitive load and task performance such that when cognitive load increases, managers attribute relatively more self-servingly with Good Performance and relatively less self-servingly with Poor Performance. Figure 2 displays this interaction, which is significant (p < 0.001, one-tailed, untabulated). Follow-up simple effects also support the prediction in H1 as the effect of load given Good Performance is to increase self-serving attributions (p = 0.009, one-tailed, untabulated) and the effect of load given Poor Performance is to decrease self-serving (i.e., increase self-disserving) attributions (p = 0.002, one-tailed, untabulated). Overall, these results suggest that managers tend to attribute both good and poor performance to internal sources when under cognitive load. [INSERT FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE] Supplemental Analyses We complement our main results with additional tests regarding managers’ awareness of their causal attributions. Our hypothesis development argues that the causal attribution process is, at least in part, automatic, suggesting that managers might not exhibit conscious awareness of their attributional locus (i.e., extent of internal vs. external attributions). We investigate this 17 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 further with two sets of post-experimental questions, both of which require participants to make explicit assessments of internal versus external attributions. We ask one question about participants’ perceived amount of internal versus external attributions in general5 and we ask four questions that ask participants to compare specific internal (effort and skill) and external (luck and difficulty) reasons6 for their performance. If managers' attribution process is entirely conscious, then their attributional locus should not depend on whether they are simply giving reasons for performance, as in our main DV reported above, or whether they are explicitly reporting on their attributional locus. However, if managers lack conscious awareness of the attribution process, explicit assessments of attributional locus will not result in responses that exhibit the same pattern as our main results. For the first question, there is no significant effect of cognitive load (p = 0.405, two-tailed, untabulated), contrary to results in Table 1 and consistent with the assumption that managers lack conscious awareness of their attributional locus. However, a null result with frequentist statistics cannot be considered confirmatory evidence (Kruschke 2011). So, we provide confirmatory evidence by using Bayesian model comparison (Kruschke 2010, 2011, 2014; Guggenmos and Bennett 2018) to show that participants’ perceived attributions do not differ based on cognitive load. Specifically, we compare an intercept-only model (i.e., the null model) to a model with a main effect of cognitive load. Results favor the null model with a Bayes factor of 4.58, which can be interpreted as meaning our data indicate the null model is 4.58 times more 5 Specifically, the first question asks participants to rate themselves on the perceived extent of internal versus external attributions in their performance reports on a 7-point scale anchored by “1 = All internal reasons” and “7 = All external reasons” with the midpoint as “4 = About the same amount of internal and external reasons”. 6 For example, for the question asking participants to compare luck and skill, we state: “Just between (a) luck and (b) skill, which played a bigger role in your performance on the trivia questions?” Participants respond on a 7-point scale anchored by 1 = “Almost all due to luck” and 7 = “Almost all due to skill” with the midpoint as 4 = “Equal amounts due to luck and skill”. 18 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 likely to accurately describe the data than the model with a main effect of cognitive load.7 This large a Bayes factor provides “substantial” or “positive” evidence supporting the null model (Jeffreys 1961; Kass and Raftery 1995). Results examining an average of the second set of questions yield similar results. The effect of cognitive load is insignificant in an ANOVA (p = 0.407, two-tailed, untabulated) and the corresponding Bayes factor comparing the null model to the model with a main effect of cognitive load is 3.36, which is also substantial, positive evidence (Jeffreys 1961; Kass and Raftery 1995) in favor of the null model. Another way to investigate the extent of awareness of the attributional process is at a participant level by comparing participants’ perceived attribution locus, from the first question above, with participants’ actual attribution locus in their respective performance reports. If the attributional process is, at least in part, automatic, we expect to see a significant lack of matching between participants’ perceived attribution locus and the attribution locus of their actual performance reports. We find that only 38 percent (53 participants) of all participants exhibit such a match, which is not significantly different than chance matching of 33 percent (z=1.264, p =0.206, two-tailed, untabulated).8 Taken together, these results suggest that participants do not seem aware of their own causal attributions. 4. Experiment Two To complement the results of our first experiment, we conduct a second experiment to rule out an alternative explanation for our main results. Instead of just reducing the cognitive resources necessary to incorporate external attributions, cognitive load might lead to less 7 We calculate Bayes factors using the BayesFactor package in the R statistical language (R Core Team, 2018). Notably, this is a conservative test since the ex ante amount of matching that would indicate complete awareness is 100 percent whereas this test is comparing to chance matching of 33 percent. 8 19 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 accurate attributions because tasks are more difficult under greater cognitive load. The task in our first experiment was structured such that external attributions, like luck and chance, were more “accurate”. Thus, the increase in internal attributions with increased cognitive load that we found in our first experiment could be due to cognitive load leading to less accurate attributions. To provide convergent evidence that cognitive load increases internal attributions rather than increasing inaccurate attributions, we conduct another experiment wherein performance is driven more by internal factors, like ability and effort.9 If cognitive load leads to less accurate attributions rather than internal attributions, we would expect to see a positive association between cognitive load and external attributions in this second experiment. Design We manipulate cognitive load (High or Low) while participants report on their performance on a slider task. Participants first attempt to correctly position 10 sliders in 30 seconds. Then, just as in experiment one, participants explain the reasons for their performance, which comprises our dependent variable and is coded just as in experiment one. Half of all participants are subject to High cognitive load and are asked to carefully listen for and remember the number of beeps (the correct number is 19) they hear while they are reporting. These same participants are given a chance to enter the number of beeps that they hear on the screen immediately following the reporting screen. Low cognitive load participants are not asked to listen for, or count, any beeps. Participants and Compensation We recruit 178 participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants average 37 years of age and 43 percent identify as female. All participants are paid a flat fee of $0.50 in addition to a bonus of $0.10 for each correctly positioned slider and a $0.50 bonus for correctly remembering 9 In fact, Choi et al. (2019) argue and show that a slider task is especially effective at revealing differences in effort, an internal factor. 20 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 the number of beeps. To keep compensation equal between conditions, participants in the Low cognitive load condition are randomly selected to receive a $0.50 bonus equal to the proportion of participants in the High cognitive load that receive a bonus. Average compensation totaled $1.29 per participant and average time to complete was 4 minutes and 19 seconds.10 Manipulation Check To check our manipulation of cognitive load, we examine the proportion of participants in the High cognitive load condition who appear to attempt to listen for and remember the number of beeps. Fifty-six percent of participants enter ‘19’, which is the correct number of beeps and 88 percent are within three beeps. Restricting our analyses to just this 88 percent leaves inferences identical, but we include all participants in all analyses for completeness. Results Experimental results are shown in Table 2. Consistent with the first experiment and in support of our hypothesis that managers automatically attribute performance internally, we find that participants’ performance reports include significantly more internal reasons for performance when cognitive load is High versus Low (t176 = 2.81, p = 0.003, one-tailed, untabulated). [INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE] 5. Survey To complement the experiments by placing the results in the context of actual disclosure settings, we survey IROs to investigate perceptions of the (a) reasons for and (b) consequences of different amounts of disclosure preparation. With more disclosure preparation, managers’ Approval for this experiment was obtained from the University’s Institutional Review Board. Completed responses were obtained from 210 participants but 32 responses include indiscernible explanations for performance (e.g., blank, “n/a,” or an unrelated copy-paste), leaving 178 responses for analysis. 10 21 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 disclosures are likely more controlled and issued under less cognitive load. We survey IROs because IROs are known as “chief disclosure officers” and are familiar and involved with firm disclosures and disclosure preparation (Brown et al. 2019; Amel-Zadeh et al. 2019). Our survey includes 114 IROs, 35 percent of which are female and 91 percent of which have ten or more years of work experience in investor relations. We include the questions for the current research as part of the survey instrument outlined in Durney (2021). We distribute the survey through the National Investor Relations Institute (NIRI) via weekly newsletters sent to all NIRI members, emails from NIRI chapter presidents, and posts on NIRI chapter LinkedIn pages. We ask two questions, the first of which, outlined in Table 3, specifically asks participants to rate the likelihood that scripting of disclosures is motivated by two different rationales. Both rationales involve avoiding disclosure of information inconsistent with the issuer’s narrative, but the first rationale involves inconsistent unfavorable information and the second reason involves inconsistent favorable information. As Table 3 shows, IROs perceive the first reason to be a likely motivator for disclosure preparation, with a mean response significantly greater than the scale midpoint (p = 0.017, two-tailed). However, survey participants did not perceive the second reason to be especially likely or unlikely, with a mean response that is not significantly different than the scale midpoint (p = 0.188, two-tailed). Thus, IROs perceive the possible disclosure of unfavorable (but not favorable) news to be a likely reason to engage in disclosure preparation.11 [INSERT TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE] The results from this first question support our experimental results and complement existing archival results. In our experiments, we provide evidence suggesting that managers automatically 11 Mean responses for the two reasons (4.81 vs. 4.45) are not significantly different from each other at conventional levels of significance in a paired t-test (p = 0.145, two tailed, untabulated). This analysis involves removing one observation because one IRO only answered for one of the reasons, making a paired t-test impossible unless that observation is dropped. An unpaired t-test with all responses yields a p-value of 0.439 (two-tailed, untabulated). 22 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 attribute performance in an unfavorable way when performance is poor – i.e., they automatically attribute poor performance internally. These survey results suggest that managers are motivated to prevent such disclosure of unfavorable information with disclosure preparation. These results also complement results from Lee (2016) that indicate one type of disclosure preparation, earnings call Q&A scripting, is more likely when managers have negative private information – i.e., when performance is poor. Lee (2016) argues that his results are due to managers’ incentives to “reduce the likelihood that bad news is unintentionally revealed” (p. 230). However, Lee (2016) does not test the intentionality of managers’ disclosure decisions in his archival analysis. Our experimental and survey results support Lee’s (2016) explanation of his results by experimentally testing the intentionality of disclosures and showing that IROs agree with Lee’s (2016) arguments. The second survey question asks about the consequences of disclosure preparation by asking IROs to rate the likelihood of two scenarios occurring in three specific disclosure venues: earnings conference call Q&As, private phone calls, and private face-to-face meetings. The first scenario is about responding to an unanticipated question with unfavorable information and the second scenario is identical to the first except the disclosed information is favorable. Importantly, this question asks about disclosures that are made in response to unanticipated questions, which is a setting with less disclosure preparation where cognitive load is likely higher. Responses to this question, shown in Table 4, suggest three important takeaways regarding the consequences of disclosure preparation. First, IROs’ responses indicate managers’ responses to unanticipated questions are usually consistent with a firm’s overall narrative. The means of all ratings are significantly below the scale midpoint (all p < 0.003, two-tailed), which is consistent 23 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 with successful disclosure preparation – e.g., the anticipation of investor questions and development of strategies to respond to unanticipated investor questions. Second, these results hold for all three disclosure settings. Pairwise t-tests show that survey participants find no difference between disclosure settings in the likelihood of the scenarios occurring (all p > 0.170, two-tailed, untabulated).12 In fact, responses for the first and second scenario indicate good internal consistency with values of Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.80 and α = 0.81, respectively. Finally, survey responses indicate that disclosure issue with less preparation more commonly involve favorable information than unfavorable information, consistent with the implication of Lee’s (2016) results that disclosure preparation, including prepping for unanticipated questions, is more focused on unfavorable information. The likelihood of the second scenario occurring is greater than the likelihood of the first scenario occurring (p < 0.001, two-tailed, untabulated).13 Collectively, these three takeaways suggest disclosure preparation reduces disclosures with inconsistent messaging and unfavorable information. [INSERT TABLE 4 ABOUT HERE] 6. Conclusion This paper investigates how the cognitive load that results from different amounts of disclosure preparation might affect managers’ explanations for performance. Two experiments manipulate cognitive load and find that increased cognitive load results in more internal attributions for performance, suggesting that internal explanations for performance are more likely to occur spontaneously when firms spend less time on disclosure preparation. The survey results complement these findings and suggest that managers use disclosure preparation to 12 We correct for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni-Holm adjustment. This analysis averages the three disclosure venues for each scenario, which is reasonable given the values of Cronbach’s alpha, and compares the means for the two scenarios of 1.94 and 2.63. 13 24 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 prevent the disclosure of unfavorable information and inconsistent messaging. The collective results indicate that when under cognitive load managers are more likely to make unfavorable disclosures in the presence of bad news. One corresponding implication is that managers’ disclosure preparation efforts are especially helpful when news is bad. Our results provide three important contributions. First, we answer a call for research by Bloomfield (2008) to investigate spontaneous disclosures (i.e., disclosures with less preparation), which vary across firms and disclosure settings and affect market outcomes (Lee 2016; Durney 2021). This paper increases our understanding about how differing levels of disclosure preparation affect disclosure characteristics. Second, our results provide evidence on how and why managers prepare for disclosures. Our experimental and survey evidence complements existing archival research by offering support for assumptions in Lee (2016) about why managers prepare for disclosures. Lastly, our findings contribute to research on managers’ causal attributions. Our results suggest that managers’ causal attributions may not always be intentional, contrary to the general assumption in most of the prior literature (Staw et al. 1983; Salancik and Meindl 1984; Baginski et al. 2000; Baginski et al. 2004; Barton and Mercer 2005; Osma and Guillamón-Saorín 2011; Chen 2012; Elliott et al. 2012; Libby and Rennekamp 2012; Kimbrough and Wang 2013; Libby and Emett 2014; Chen et al. 2016). Our study is subject to limitations, which suggest avenues for future research. Our use of abstract tasks increases internal validity in our experiments but may lack external validity and generalizability. As such, our results suggest differences in managers’ actual disclosures in different reporting settings that we do not test. For example, in the 10-K’s MD&A or in press releases, managers are more likely to disclose only after substantial preparation – i.e., with less cognitive load. On the other hand, in the earnings call Q&As, private meetings with investors, or 25 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 in interviews with the press, managers’ disclosures are more likely to be issued under greater cognitive load. To the extent that all explanations for firm performance are external to the preparer of a given disclosure, this could limit the generalizability of our results. However, consistent with prior work involving the application of attribution theory to managers (e.g., Staw et al. 1983; Baginski et al. 2004; Barton and Mercer 2005; Elliott et al. 2012; Kimbrough and Wang 2013), we believe that in most cases, explanations for firm performance that are internal to the firm (e.g., that result from firm-level decisions) are more likely to be accessible than explanations that are external to the firm. Although our study does not directly test managers’ actual disclosures, future research could investigate the differences in actual disclosures that occur due to differences in preparation or cognitive load. Additionally, the generalizability of our results also depends on whether the abstract tasks in our experiments reflect relevant features of the financial reporting setting. We explicitly chose to abstract from reality in order to avoid unnecessary realism when examining a psychological process (Libby et al. 2002; Libby et al. 2015; Griffith et al. 2016; Kadous and Zhou 2017). As such, the current research complements studies that allow participants to draw on their actual experience when explaining performance in a more realistic setting as in Asay et al. (2018). Further research might incorporate various institutional elements of the financial reporting setting and examine corresponding effects. Finally, we focus our investigation on managers’ attributional locus, but future research might focus on other dimensions of managers’ causal attributions and other features of managers’ explanations that might differ if issued with varying levels of preparation or cognitive load. 26 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Appendix: Trivia Questions What animal is the second most common rabies carrier in the United States? - Racoon - Bat Alexander the Great was a student of what Greek philosopher? - Aristotle - Socrates How many total toes does an Ostrich have? - Four - Six What was the name of the Apollo 11 lunar module? - Odyssey - Eagle What is the longest book in the Harry Potter series? - Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix - Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows How long does it take a human blood cell to make a complete circuit of the human body? - One minute - Ten minutes What are some wild gerbils in China fed in order to control their numbers? - Arsenic - Birth control pills This appendix presents the trivia question that are used in experiment one. Questions and possible answers were shown in random order. 27 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 References Abenate, M. 2018. The Pros and Cons of Switching From Quarterly To Semiannual Reporting. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2018/10/12/the-pros-andcons-of-switching-from-quarterly-to-semiannual-reporting/. Aerts, W. 2005. Picking up the pieces: impression management in the retrospective attributional framing of accounting outcomes. Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (6): 493-517. Amel-Zadeh, A., A. Scherf, and E. F. Soltes. 2019. Creating firm disclosures. Journal of Financial Reporting (forthcoming). Asay, H. S. 2018. Horizon‐induced optimism as a gateway to earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research 35 (1): 7-30. Asay, H. S., R. Libby, and K. M. Rennekamp. 2018. Firm performance, reporting goals, and language choices in narrative disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 65 (2-3): 380-398. Asay, H. S., R. Guggenmos, K. Kadous, L. Koonce, and R. Libby. 2021. Theory testing and process evidence in accounting experiments. Working paper, Cornell University, Emory University, University of Iowa, and University of Texas. Asay, H. S., S. Clor-Proell, M. Durney. 2021. Behind closed doors: An investigation of Investor Relations Officer Disclosures in Private Meetings with Investors. Working paper, Texas Christian University and University of Iowa. Baginski, S. P., J. M. Hassell, and W. A. Hillison. 2000. Voluntary causal disclosures: Tendencies and capital market reaction. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 15 (4): 371–89. Baginski, S. P., J. M. Hassell, and M. D. Kimbrough. 2004. Why do managers explain their earnings forecasts? Journal of Accounting Research 42 (1): 1–29. Bargh, J. A., and E. L. Williams. 2006. The automaticity of social life. Current Directions in Psychological Science 15 (1): 1-4. Barton, J., and M. Mercer. 2005. To blame or not to blame: Analysts’ reactions to external explanations for poor financial performance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39 (3): 509–33. Beckman, L. 1973. Teachers' and observers' perceptions of causality for a child's performance. Journal of Educational Psychology 65 (2): 198-204. Bettman, J. R., and B. A. Weitz. 1983. Attributions in the Board Room: Causal Reasoning in Corporate Annual Reports. Administrative Science Quarterly 28 (2): 165–83. Bloomfield, R. 2008. Discussion of “Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence”. Journal of Accounting and Economics 45 (2): 248-52. Böhm, G., and H. R. Pfister. 2015. How people explain their own and others’ behavior: a theory of lay causal explanations. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 139. 28 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Brown, L. D., A. C. Call, M. B. Clement, and N. Y. Sharp. 2019. Managing the narrative: Investor relations officers and corporate disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 67 (1): 58-79. Campbell, K. W., and C. Sedikides. 1999. Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: A metaanalytic integration. Review of General Psychology 3 (1): 23–43. Chance, D., J. Cicon, and S. P. Ferris. 2015. Poor performance and the value of corporate honesty. Journal of Corporate Finance 33: 1-18. Chen, Z. 2012. Internal and External Attributions by Managers in Earnings Conference Calls. Doctoral dissertation, Duke University. Chen, W., J. Han, and H. T. Tan. 2016. Investor reactions to management earnings guidance attributions: The effects of news valence, attribution locus, and outcome controllability. Accounting, Organizations and Society 55: 83-95. Choi, W., J. Clark, and A. Presslee. 2019. Testing the Effect of Incentives on Effort Intensity using Real-Effort Tasks. Working paper. Durney, M. T. 2021. Managers’ Private Disclosures: Descriptive Evidence and the Effect of Audience Size. Working paper, University of Iowa. Duval, T. S., and P. J. Silvia. 2002. Self-awareness, probability of improvement, and the selfserving bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82 (1): 49–61. Elliott, W. B., Hodge, F. D., and L. M. Sedor. 2012. Using online video to announce a restatement: Influences on investment decisions and the mediating role of trust. The Accounting Review 87 (2): 513–35. Epley, N., K. Savitsky, and T. Gilovich. 2002. Empathy neglect: Reconciling the spotlight effect and the correspondence bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83 (2): 300-12. Gilbert, D. T., and D. H. Silvera. 1996. Overhelping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (4): 678-90. Gilovich, T., J. Kruger, and V. H. Medvec. 2002. The spotlight effect revisited: Overestimating the manifest variability of our actions and appearance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 38 (1): 93-9. Gilovich, T., V. H. Medvec, and K. Savitsky. 2000. The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one's own actions and appearance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78 (2): 211-22. Griffith, E. E., K. Kadous, and D. Young. 2016. How insights from the “new” JDM research can improve auditor judgment: Fundamental research questions and methodological advice. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 35 (2): 1-22. Guggenmos, R. D., and G. B. Bennett. 2018. The Effects of Company Image and Communication Platform Alignment on Investor Information Processing. Working paper, Cornell University and University of Massachusetts Amherst. Hasbro. 2009. Trivial Pursuit: Master Edition. [Board Game]. Pawtucket, RI. 29 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Heider, F. 1944. Social perception and phenomenal causality. Psychological Review 51 (6): 35874. Heider, F. 1958. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (Vol. ix). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Hirshleifer, D., and S. H. Teoh. 2003. Limited Attention, Information Disclosure, and Financial Reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 36 (1–3): 337-86. Jeffreys, H. 1961. Theory of Probability. (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kass, R. E., and A. E. Raftery. 1995. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 773-95. Kadous, K., and Y. Zhou. 2017. Maximizing the contribution of JDM-style experiments in accounting. The Routledge Companion to Behavioural Accounting Research, edited by T. Libby and L. Thorne. Routledge. Kimbrough, M. D., and I. Y. Wang. 2013. Are seemingly self-serving attributions in earnings press releases plausible? Empirical evidence. The Accounting Review 89 (2): 635–67. Kruschke, J. K. 2010. What to believe: Bayesian methods for data analysis. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14 (7): 293–300. Kruschke, J. K. 2011. Bayesian assessment of null values via parameter estimation and model comparison. Perspectives on Psychological Science 6 (3): 299–312. Kruschke, J. 2014. Doing Bayesian Data Analysis: A Tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan. Academic Press. Land, H. 2019. Late Filings, Restatements, and Limited Attention. Doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester. Lee, F., C. Peterson, and L. Z. Tiedens. 2004. Mea culpa: Predicting stock prices from organizational attributions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30 (12): 1636-49. Lee, J. 2016. Can investors detect managers' lack of spontaneity? Adherence to predetermined scripts during earnings conference calls. The Accounting Review 91 (1): 229-50. Libby, R., R. Bloomfield, and M. W. Nelson. 2002. Experimental research in financial accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society 27 (8): 775-810. Libby, R., and S. A. Emett. 2014. Earnings presentation effects on manager reporting choices and investor decisions. Accounting and Business Research 44 (4): 410-38. Libby, R., and K. M. Rennekamp. 2012. Self-serving attribution bias, overconfidence, and the issuance of management forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research 50 (1): 197–231. Libby, R., K. M. Rennekamp, and N. Seybert. 2015. Regulation and the interdependent roles of managers, auditors, and directors in earnings management and accounting choice. Accounting, Organizations and Society 47: 25-42. Malle, B. F. 2011a. Time to give up the dogmas of attribution: An alternative theory of behavior explanation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 44: 297–352. 30 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Malle, B. F. 2011b. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee, D. (Ed.), Theories in Social Psychology (pp.72-95). Wiley-Blackwell. Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., and B. L. Hankin. 2004. Is There a Universal Positivity Bias in Attributions? A Meta-Analytic Review of Individual, Developmental, and Cultural Differences in the Self-Serving Attributional Bias. Psychological Bulletin 130 (5): 711–47. Miller, D. T. 1976. Ego involvement and attributions for success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34 (5): 901-06. Miller, D. T., and M. Ross. 1975. Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin 82: 213-25. Osma, B. G., and E. Guillamón-Saorín. 2011. Corporate governance and impression management in annual results press releases. Accounting, Organizations and Society 36 (4): 187-208. R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at http://www.Rproject.org/. Rennekamp, K. M., B. A. Steenhoven, and B. J. White. 2021. Emotion suppression and firm disclosures. Working paper, Cornell University, University of Texas, and Queen’s University. Ross, M., and F. Sicoly. 1979. Egocentric biases in availability and attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (3): 322-36. Sakaki, M., and K. Murayama. 2013. Automatic ability attribution after failure: A dual process view of achievement attribution. PLOS ONE 8 (5): e63066. Salancik, G. R., and J. R. Meindl. 1984. Corporate attributions as strategic illusions of management control. Administrative Science Quarterly 29 (2): 238–54. Savitsky, K., N. Epley, and T. Gilovich. 2001. Do others judge us as harshly as we think? Overestimating the impact of our failures, shortcomings, and mishaps. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (1): 44-56. Schopler, J., and B. Layton. 1972. Determinants of the self-attribution of having influenced another person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 22 (3): 326. Staw, B. M., P. I. Mckechnie, and S. M. Puffer. 1983. The justification of organizational performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 28 (4): 582–600. Van Dillen, L. F., E. K. Papies, and W. Hofmann. 2013. Turning a blind eye to temptation: How cognitive load can facilitate self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104 (3): 427–43. Wolosin, R. J., Sherman, S. J., and A. Till. 1973. Effects of cooperation and competition on responsibility attribution after success and failure. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 9 (3): 220-35. 31 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Zhou, Dexin, 2014, The Blame Game. Working paper, City University of New York. 32 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 TABLE 1 Performance Condition Experiment One Descriptive Statistics and ANOVA Results: Causal Attribution Locus in Participant Performance Reports Panel A: Descriptive statistics of causal attributions in participant performance reports: mean, (standard deviation), and number of participants Cognitive Load Condition Low Load High Load Total 0.097 0.541 0.338 Good (0.790) (0.730) (0.784) Performance n=31 n=37 n=68 -0.051 0.484 0.186 Poor (0.857) (0.677) (0.822) Performance n=39 n=31 n=70 0.014 0.515 0.261 Total (0.825) (0.702) (0.804) n=70 n=68 n=138 Panel B: ANOVA results Source Load Performance Load x Performance df 1 1 1 Mean squares 8.178 0.358 0.071 Error 134 0.594 F- statistic 13.777 0.603 0.120 p-value <0.001† 0.439 0.730 Notes: This table provides descriptive statistics and hypothesis tests for the effect of cognitive load and task performance on participants’ use of causal attributions in their performance reports. The experiment varies cognitive load (high or low) and performance on an abstract task (good or poor performance) in a 2x2 between-participants design. Participants provide narrative performance reports after learning their task performance. The dependent variable shown here is the result of two coders’ agreed-upon ratings (ranging from -1 to 1) of causal attribution locus (i.e., the extent of internal versus external causal attributions) in participants’ performance reports. Coders assign ‘1’ to performance reports with mostly internal attributions, ‘-1’ to reports with mostly external attributions, and ‘0’ to reports with an equal amount of internal and external attributions. †One-tailed equivalent due to directional prediction. All other p-values are two-tailed. 33 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 TABLE 2 Experiment Two Descriptive Statistics: Causal Attribution Locus in Participant Performance Reports Descriptive statistics of causal attributions in participant performance reports: mean, (standard deviation), and number of participants Cognitive Load Condition Low Load High Load Total -0.082 0.259 0.073 (0.812) (0.803) (0.824) 97 81 178 Notes: This table provides descriptive statistics on experiment two’s main dependent variable. The experiment varies cognitive load (high or low) on an abstract task in a 1x2 between-participants design. Participants provide narrative performance reports after performing the task. The dependent variable shown here is the result of two coders’ agreed-upon ratings (ranging from -1 to 1) of causal attribution locus (i.e., the extent of internal versus external causal attributions) in participants’ performance reports. Coders assign ‘1’ to performance reports with mostly internal attributions, ‘-1’ to reports with mostly external attributions, and ‘0’ to reports with an equal amount of internal and external attributions. 34 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 TABLE 3 Likelihood of Reasons for Disclosure Preparation – IRO Survey Question Without scripting, issuer representatives might disclose unfavorable information inconsistent with the issuer's narrative/message. Without scripting, issuer representatives might disclose favorable information inconsistent with the issuer's narrative/message. Mean P-value of t-test for difference from scale midpoint 4.81 0.017 4.45 0.188 Notes: Table 3 shows IRO survey participant responses to the following: “Please rate the likelihood that the following reasons are contributing to the scripting of issuer responses to anticipated questions from investors/analysts.” The two reasons given are shown in the table above and participants rate the likelihood of both reasons on 7-point scales with 1 = Very unlikely and 7= Very likely. P-values result from tests of whether the average response is different than four, the scale midpoint. All p-values are two-tailed. 35 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 TABLE 4 Consequences of Disclosure Preparation – IRO Survey Questions Mean P-value of t-test for difference from scale midpoint Scenario 1: In response to an unanticipated question, an issuer representative discloses unfavorable information inconsistent with the issuer's narrative/message during the following: Earnings conference call Q&As Private face-to-face meetings Private phone calls 1.970 1.853 2.030 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Scenario 2: In response to an unanticipated question, an issuer representative discloses favorable information inconsistent with the issuer's narrative/message during the following: Earnings conference call Q&As Private face-to-face meetings Private phone calls 3.030 2.471 2.441 0.003 <0.001 <0.001 Notes: Table 4 shows IRO survey participant responses regarding the likelihood of two scenarios in three disclosure settings., which are shown in the table above. The likelihood of the scenarios is rated on 7-point scales with 1= “Very unlikely” and 7= “Very likely.” P-values result from tests of whether the average response is different than four, the scale midpoint. All p-values are two-tailed. 36 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Figure 1 The Effect of Load and Performance on the Locus of Causal Attributions in Experiment One 1 0.5 Good Performance 0 Poor Performance -0.5 -1 Low Load High Load Notes: This figure displays results for the effect of load and performance on participants’ locus (i.e., internal or external) of causal attributions in their performance reports. The experiment varies cognitive load (high or low) and performance on an abstract task (good or poor performance) in a 2x2 between-participants design. Participants provide narrative performance reports after learning their task performance. The dependent variable shown here is the result of two coders’ agreed-upon ratings (ranging from -1 to 1) of the extent of internal versus external causal attributions in the performance reports. The dependent variable equals ‘1’ for performance reports with mostly internal attributions, ‘-1’ for reports with mostly external attributions, and ‘0’ for reports with an equal amount of internal and external attributions. 37 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813 Figure 2 The Effect of Load and Performance on the Extent of Self-Serving Attributions in Experiment One 1 0.5 Good Performance 0 Poor Performance -0.5 -1 Low Load High Load Notes: This figure displays results for the effect of load and performance on participants’ use of self-serving attributions in their performance reports. The experiment varies cognitive load (high or low) and performance on an abstract task (good or poor performance) in a 2x2 between-participants design. Participants provide narrative performance reports after learning their task performance. The dependent variable shown here is the result of two coders’ agreed-upon ratings (ranging from -1 to 1) of the extent of internal versus external causal attributions in the performance reports. Self-serving (self-disserving) attributions are internal (external) attributions with good performance and external (internal) attributions with poor performance. The dependent variable equals ‘1’ for performance reports with mostly self-serving attributions, ‘-1’ for reports with mostly self-disserving attributions, and ‘0’ for reports with an equal amount of self-serving and self-disserving attributions. 38 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3469813