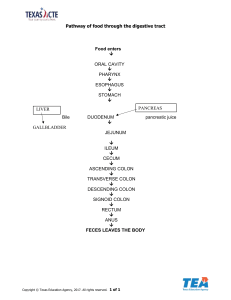

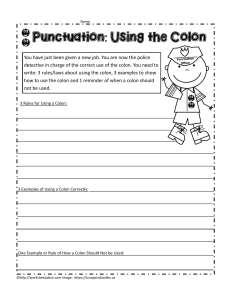

Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 DOI 10.1007/s12156-010-0061-0 REVIEW Colon cancer in rapidly developing countries: review of the lifestyle, dietary, consanguinity and hereditary risk factors Abdulbari Bener Received: 29 October 2009 / Accepted: 5 August 2010 / Published online: 17 August 2010 Ó Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Colon cancer rates are rising dramatically in once low incidence nations. These nations are undergoing rapid economic development and are known as ‘‘nations in transition’’ (NIT). This review identifies some of the most common etiological risk factors of colon cancer in these nations and evaluates the existing epidemiological evidence. The main risk factors which were found to be prevalent in NIT include: lifestyle factors such as physical inactivity, obesity and abdominal adiposity, alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking; dietary factors such as fatty food and red meat consumption. Protective factors included white meat and fiber consumption. Several studies found to have significantly higher rates of colon cancer among the young population (\40 years old). There appears to be a quantitative and qualitative increase in risk to relatives of patients diagnosed at a young age compared with those diagnosed later in life, at least part of which is likely to be the result of a hereditary susceptibility. Close relatives of patients with colon cancer are at an increased risk of developing a colon cancer. Close relatives of early onset cases warrant more intensive endoscopic screening and at an earlier age than relatives of patients diagnosed at A. Bener (&) Department of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Hamad Medical Corporation, PO Box 3050, Doha, Qatar e-mail: abener@hmc.org.qa; abb2007@qatar-med.cornell.edu A. Bener Department of Public Health, Weill Cornell Medical College, PO Box 3050, Doha, Qatar A. Bener Department of Evidence for Population Health Unit, School of Epidemiology and Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK older ages. Furthermore, these suggest the existence of genetic predispositions in these nations which need to be investigated further and have implications for screening programs. In conclusion, public health awareness campaigns promoting prevention of modifiable risk factors and screening initiatives with guidelines suited to the age-specific incidence rates of NIT are needed very urgently. Keywords Epidemiology Colon cancer Life-style Dietary Consanguinity Hereditary Background Colon cancer is strongly correlated with various environmental and genetic factors, which make primary prevention fundamental to public health initiatives [1]. While high colon cancer incidence rates were mainly found in developed nations, these are now increasing dramatically in rapidly developing nations [2] (Fig. 1). These rapidly developing countries are known as ‘‘nations in transition’’ (NIT). Although other reviews have noted these trends and documented the various screening programs around the globe [3], none have specifically looked at the common etiological factors in these nations, which are contributing to these rising trends. Colon cancer has many known preventable risk factors which numerous studies have documented. Each risk factor has different degrees of association with colon cancer, especially in relation to geographic location. Previous reviews related to colon cancer have focused on specific risk factors such as physical inactivity [4], dietary fiber intake [5], red meat intake [6] obesity [7] and the hereditary syndromes and genetics of colon cancer [8]. This review differs from these in that it will provide an overview 123 6 Fig. 1 Cycle of exposure to colon cancer risk in developed and developing nations. Once low incidence and risk regions (developing nations) slowly get exposed to risk factors which increase the incidence of disease, while high incidence regions implement strategies and campaigns to reduce exposure to risks and stabilize or decrease the incidence of disease. *All rates are for males [3] Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 NATIONS IN TRANSITION Increasing Rates of Colon Cancer DEVELOPING NATIONS • Improving SES and affluence Example: Low Incidence Rates of Colon Cancer • Have lowest SES Example: India (4.1/100.000)* • Dietary / Lifestyle Habits • High fiber • Low meat • Low Fat/Sugar • High Vegetables and Fruit intake. • Kuwait (15/100,000)* Dietary Habits: • Low fiber • Higher Meat intakes • High Fat & refined Carbohydrate Lifestyle • Sedentary • Increasing Obesity Rates Developed Nations High incidence rates but stable or decreasing • Have high SES Example: • USA (41/100 000)* Introduced Prevention Programs • Encouraged Physical Activity • Low fat, high fiber diets • Campaigns against Smoking and Alcohol consumption Introduced Screening Programs of the combination of risk factors that have led to the rising trends of colon cancer in NIT (Fig. 2). Epidemiology The highest incidence rates of colon cancer are found in the wealthiest developed nations, while the lowest rates are found in some of the poorest developing nations [3] (Table 1). This geographic variation has been mainly attributed to the differences in diet and lifestyle. This proposition has been confirmed by the numerous ‘‘migration studies’’ which have documented the dramatic rise in incidence rates of colon cancer in migrants from low incidence regions, who have settled in high incidence regions [9]. Moreover, in recent years, with the economic development of many nations (NIT), rates of colon cancer are rapidly on the rise, while rates in previously high 123 incidence regions have stabilized if not slightly decreased, largely due to intervention and screening programs [3]. A common finding is that the highest colon cancer incidence rates are found in the urban centers of these nations [10]. In contrast to developed nations, many developing and NIT have significantly higher rates of young individuals (\40 years) with colon cancer [11–13]. Men and women have a similar lifetime risk of developing colon cancer of 6% although they are affected differently by the etiological risk factors, which will be elaborated further throughout this paper [14]. Lifestyle risk factors Changing lifestyle habits in NIT have been persistently presented as key contributing factors to the increasing trends of colon cancer [15]. Indeed, the most consistent Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 7 Lifestyle Factors 36 65 37 85 66 67 Hereditary Factors 40 Dietary Factors Fig. 2 Venn diagram showing the overlapping of lifestyle with dietary and hereditary risk factors for colon cancer of Qatari studied subjects (both cases and controls) (N = 428*)#. *Total number of cases and controls in Venn diagram = 396 as 32 controls did not have any of the three risk factors. Dietary factor = 283, hereditary factor = 229, lifestyle factor = 223. #Bener et al. (2010). Impacts of family history and life style habits on colorectal cancer risk: a case–control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (in press) Table 1 Estimated global cases of colorectal cancer in 2008 Estimated numbers of cases (thousands) Men Women Both sexes World 663 570 1,233 More developed regions 389 337 726 Less developed regions 273 232 505 WHO European region 238 211 449 WHO Western Pacific region 224 170 394 WHO Americas region 122 118 240 WHO South East Asian regions 50 47 97 WHO African region WHO Eastern Mediterranean region 14 13 12 10 26 23 European union 182 150 332 China 125 95 48 USA 79 74 153 India 20 16 36 Globocan 2008 cancer fact sheet. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/ factsheets/cancers/colorectal.asp. Accessed 20 June 2010 epidemiological evidence links physical inactivity, obesity, and central adiposity with increased colon cancer risk [4, 16, 17]. Physical activity is generally accepted as a protective factor for colon cancer; evidence from both prospective and case–control studies has been strong and consistent [18]. These wide-ranging studies have found consistent relations between physical activity and risk of colon cancer for both genders, in a wide spectrum of populations and thus it is unlikely that all these relations are due to uncontrolled confounding [19]. Indeed physically active men and women are at around half the risk of developing colon cancer than their less active counterparts [20]. The shift from manual to sedentary work and leisure activities in NIT are allowing these populations at increased risk of developing colon cancer [21]. Thus, it is not surprising that colon cancer rates were found to be the highest in the main cities (i.e. urbanized areas) where sedentary lifestyles were predominantly prevalent [10, 15]. Another explanation for limited physical activity in some of these NIT is the hot and humid climate which restricts the amount of time spent outdoors [22]. Coinciding with these more sedentary lifestyle habits are increased in the consumption of foods high in fat, sugar, and salt which have led to soaring obesity rates, particularly in urbanized regions of NIT [21]. In fact, studies conducted in both developed nations and NIT have documented obesity as a risk factor for colon cancer [16, 23]. Obesity has generally been found to be a stronger risk factor for men [24]. Stronger associations have been documented for central adiposity than BMI [17, 25]. In contrast to BMI, stronger associations between colon cancer risk and central adiposity were observed for women [17]. Other major lifestyle risk factors of colon cancer include alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking. The evidence is consistent and strong relating alcohol consumption and colon cancer risk; however, this only appeared to be the case among men [26, 27]. Cigarette smoking was found to increase colon cancer risk, in both genders, in all sites of the colon [26, 28]. Alcohol consumption levels are very low in many nations that lie within NIT as it is prohibited for cultural or religious reasons, some of these nations have even prohibited the sale of alcohol, thus alcohol consumption has a minimal effect on colon cancer rates in many NIT [29]. On the other hand, the increasing rates of smoking, in developing nations and NIT is a worrying trend that has implications for the rising trends of colon cancer [30]. More studies are needed in these regions to determine the sociocultural factors related to the increased number of smokers, in order to establish effective anti-smoking campaigns. Dietary risk and protective factors Dietary factors have also been associated with colon cancer; however, their relations are somewhat weaker than the previously mentioned lifestyle risk factors. Fat intake has been proposed to be associated with colon cancer risk. While the theoretical evidence appears plausible, the epidemiological evidence is very weak. For instance Slattery’s (1997) [31] study of fat intake among various age-groups 123 8 found that only fat intake from food preparation was associated with increased risk of colon cancer in older women, but no relation was observed for any other demographic group. These findings were confirmed by the North Carolina Colon Cancer Study [32] which found no association between trans-fatty acid intake and colon cancer risk, in a large cohort of African Americans and Whites from various geographical areas; other studies have documented similar results [33]. Like dietary fat intake, many theoretical associations between red meat intake and colon cancer have been proposed. This has been persistently presented as a risk factor, as dramatically higher consumption of red meat exists in developed countries where incidence rates of colon cancer are markedly higher, than in developing countries where consumption levels of red meat are low [34]. Indeed, with increasing affluence, consumption levels of red meat have risen considerably in NIT where incidence rates of colon cancer are also on the rise [35]. The epidemiological evidence has generally associated red meat consumption with increased colon cancer risk. Both the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort [36] and the prospective EPIC cohort study [37] found that red meat intake was positively associated with increased colon cancer risk; however, these findings were not statistically significant. Nonetheless the EPIC cohort study found after further analyses of the subgroups of red meats, where intake of each meat was mutually adjusted for intake of the other meats, only the trend for increased colorectal cancer risk with increased pork intake remained statistically significant [37]. White meat (fish and poultry) on other hand, was found to either not increase the risk of colon cancer or was even protective against it [37, 38]. In particular, poultry was found to contain methionine, which has a protective effect against cancer [39]. High consumption of fiber, whether through cereal or plant sources, was thought to be a large determinant in the huge gap in incidence rates of colon cancer globally [40]. Thus, it was proposed that in NIT, people were consuming less fiber in their diets due to changes to ‘‘Westernized’’ diets. Indeed, many biological theories have been proposed for fiber’s role in reducing colon cancer risk [41]. Numerous case–control [5, 42, 43] and prospective studies [44, 45] have confirmed the protective effect of fiber intake against colon cancer. However, this protective effect was found to slightly differ between the genders and type of fiber intake. For instance, the inverse association between fiber from whole grain sources and colon cancer was found to be stronger among men [40]; on the other hand, the inverse association between fiber from vegetable and fruit sources and colon cancer was found to be stronger among women [41]. 123 Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 Hereditary factors and consanguinity Unlike the dietary and lifestyle risk factors for colon cancer, hereditary colon cancer is not modifiable; however, a good knowledge of such a family history has implications for early detection and screening. Most recently, study by Katalinic et al. [46] reported that taking familial and hereditary risks into account a total of 6.7% of all Germans in the age group 30–49 years would be classified as familial risk persons. Approximately 20% of colon cancer diagnoses have some definable hereditary factor while specific germline mutations are characterized in approximately 5% of all colon cancer cases [47]. The three main hereditary forms of colon cancer are: hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) which is the most commonly occurring hereditary syndrome with an estimated incidence of 5–7% of all colon cancer cases [48]; Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) which is inherited as an autosomal dominant manner [48]; and familial colon cancer where no specific gene is identified but colon cancer occurs in numerous first degree family members [8]. Each syndrome has different symptoms and results in colon cancer in different sites of the colon [8]. However, a common factor that they all share is the early onset of diagnosis, usually \40 years of age [49, 50]. The relatively large incidence of colon cancer among young adults (those \40) in developing countries in comparison to developed countries, has led to speculation about the genetic predisposition of people living in these regions for colon cancer [51, 52]. Indeed, this finding was consistent across developing nations ranging 20–30% in countries including: Egypt [51], Jordan [49], Saudi Arabia [52], Iran [12], and among native South Africans [11]. While this trend has been observed in these countries, very few studies have gone beyond this observation and conducted research to explore the mechanism/s and the causes for this difference. One of the main studies which have investigated this finding further was conducted among the native population in South Africa [11]. This study [11] found that one of the main pathways of colon cancer was HPNCC––indeed, noted that it was difficult to collect accurate information about family history and so devised a molecular technique to do so. Similar studies have been conducted in Egypt [51], and Taiwan [53] and found that there were unique pathways of colorectal cancer among their populations in comparison to ‘‘western populations’’. Several studies found to have significantly higher rates of colon cancer among the young population (\40 years old) [46–53]. There appears to be a quantitative and qualitative increase in risk to relatives of patients diagnosed at a young age compared with those diagnosed later in life, at least part of which is likely to be the result of a hereditary susceptibility. Close relatives of patients with colorectal Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 cancer are at an increased risk of developing a colon cancer. Close relatives of early onset cases warrant more intensive endoscopic screening at an earlier age than relatives of patients diagnosed at older ages. [54]. Furthermore, these suggest the existence of genetic predispositions in these nations which need to be investigated further and have implications for screening programs. Another possible explanation for the high incidence rates among young people in developing countries and NIT is the practice of consanguinity [55]. Consanguinity is common in nations of the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and South East Asia where many of NIT are located [56]. Since colon cancer is inherited as an autosomal dominant manner, consanguinity increases its potential incidence [56]. The role of consanguinity in colon cancer incidence rates has been investigated, in a small pilot study in Egypt [50] and in a larger representative cross-sectional study in Qatar [56], these studies found that colon cancer rates were higher in those who had consanguineous parents. No study has of yet been conducted to investigate the mechanism through which consanguinity impacts on colon cancer. Nonetheless, while genetic predisposition may explain to a large extent the incidence of colon cancer in young people in developing countries and NIT, a few other factors need to be considered which also play a role in explaining this phenomenon. One of the main other explanations for the high incidence of colon cancer among those under 40 years in these regions is the young age structure of populations; whereas in developed nations, they tend to have an ‘‘aging population’’ [12]. Moreover, this younger generation, tends to be more conforming to western lifestyle habits which are conducive to colon cancer, in comparison to the older generation who have very low incidence rates [57]. Furthermore, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States [58] in both men and women and is thus a major public health problem, in 2007, approximately 153,760 people in the United States were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and about 52,180 died of the disease, overall prevalence of those at risk for hereditary colorectal cancer in United States was 26% for all sites, ranging 11–39% across sites and tools. This study is significant because it revealed a fairly high percentage of people at risk for hereditary colorectal cancer and showed how an initial risk assessment can be easily done by professional nurses and other healthcare providers who are in a unique position to help reduce the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer. The hereditary nature of colon cancer has implications for screening initiatives. With such high incidence rates among the young, in NIT and developing nations, guidelines which suggest screening for those above 50 need to be reconsidered and readdressed [59]. 9 Conclusion The rising rates of colon cancer in NIT can be attributed to lifestyle, dietary and hereditary factors. The literature reported significantly higher rates of colon cancer among the young population (\40 years old). There appears to be a quantitative and qualitative increase in risk to relatives of patients diagnosed at a young age compared with those diagnosed later in life, at least part of which is likely to be the result of a hereditary susceptibility. Close relatives of patients with colorectal cancer are at an increased risk of developing a colorectal. Close relatives of early onset cases warrant more intensive endoscopic screening at an earlier age than relatives of patients diagnosed at older ages. While rates in NIT have not yet reached those of developed nations, the growth is rapid and demands immediate action in terms of modifying risk factors, and implementing screening guidelines and programs that represent the threat of colon cancer in these regions. Conflict of interest I declare that no benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. I also declare that I have no conflict of interest in connection with this paper. References 1. Nystrom M, Mutanen M (2009) Diet and epigenetics in colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol 15(3):257–263 2. Rehman MU, Buttar QM, Khawaja MI, Khawaja MR (2009) An impending cancer crisis in developing countries: Are we ready for the challenge? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10:719–720 3. Center M, Jemal A, Smith RA, Ward E (2009) Worldwide variations in colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 59:366–378 4. Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, Lee I-M (2009) Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Brit J Cancer 100:611–616 5. Howe GR, Benito E, Castelleto R et al (1992) Dietary intake of fiber and decreased risk of cancer of the colon and rectum: evidence from the combined analysis of 13 case–control studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 84:1887–1896 6. McAfee AJ, McSorley EM, Cuskelly GJ, Moss BW, Wallace JMW, Bonham MP, Fearon AM (2010) Red meat consumption: an overview of the risks and benefits. Meat Sci 84:1–13 7. Giovannucci E (2002) Obesity, gender, and colon cancer. Gut 51:147 8. Rustgi AK (2007) The genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Genes Dev 21:2525–2538 9. Wilmink AB (1997) Overview of the epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 40:483–493 10. Khuhaprema T, Srivatanakul P (2008) Colon and rectum cancer in Thailand: an overview. Jpn J Clin Oncol 38(4):237–243 11. Cronjéa L, Beckerc PJ, Patersona AC, Ramsay M (2009) Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer is predicted to contribute towards colorectal cancer in young South African blacks. S Afr J Sci 105:68–72 12. Mahdavinia M, Bishehsari F, Ansari R, Norouzbeigi N, Khaleghinejad A, Hormazdi M, Rakhshani N, Malekzadeh R 123 10 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 (2005) Family history of colorectal cancer in Iran. BMC Cancer 5:112 Soliman AS, Bondy ML, Levin B, Hamza MR, Ismail K, Ismail S, Hammam HM, el-Hattab OH, Kamal SM, Soliman AG, Dorgham LA, McPherson RS, Beasley RP (1997) Colorectal cancer in Egyptian patients under 40 years of age. Int J Cancer 71(1):26–30 Osias GL, Osias KB, Srinivasan R (2001) Colorectal cancer in women: an equal opportunity disease. JAOA 101 (12) Part 2; S7–S12 Ibrahim EM, Zeeneldin AA, El-Khodary TR, Al-Gahmi AM, Bin Sadiq BM (2008) Past, present and future of colorectal cancer in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol 14(4):178–182 Serrano MJGO, Carrasco MA, Ortiz R, Cazadord AC (2010) The impact of obesity on the histopathological characteristics of colorectal tumours. An observational study. CIR ESP 87(1):33–38 Kim YJ, Kim YJ, Lee S (2009) An association between colonic adenoma and abdominal obesity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol 9:4 Slattery ML, Potter JD (2002) Physical activity and colon cancer: Confounding or interaction? Med Sci Sports Exerc 34(6): 913–919 Giovannucci E (2007) Metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, and colon cancer: a review. Am J Clin Nutr 86(suppl):836S–842S Batty D, Thune I (2000) Does physical activity prevent cancer? Evidence suggests protection against colon cancer and probably breast cancer. BMJ 321:1424–1425 (editorials) World Health Organization (2010) Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations, ‘The nutrition transition and obesity’. http://www.fao.org/FOCUS/E/obesity/obes2.htm. Accessed 20 June 2010 Bener A, Ali R, El Ayoubi HR (2010) Impacts of family history and life style habits on colorectal cancer risk: a case–control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (in press) Zheng MC, Kong LH, Lu ZH, Fang YJ, Pan ZZ, Zhu YP, Wen YS, Wan DS (2009) Relationship between body mass index and colon cancer. Chin J Cancer 28(9):1–4 Kim SE, Shim KN, Jung SA, Yoo K, Moon IH (2007) An association between obesity and the prevalence of colonic adenoma according to age and gender. J Gastroenterol 42(8):616–623 Nock NL, Thompson CL, Tucker TC, Berger NA, Li L (2008) Associations between obesity and changes in adult BMI over time and colon cancer risk. Obesity 16(5):1099–1104 Otani T, Iwasaki M, Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Hanaoka T, Inoue M, Tsugane S (2003) Alcohol consumption, smoking, and subsequent risk of colorectal cancer in middle-aged and elderly Japanese men and women: Japan public health center-based prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12:1492–1500 Yi SW, Sull JW, Linton JA, Nam CM, Ohrr H (2010) Alcohol consumption and digestive cancer mortality in Koreans: the Kangwha cohort study. J Epidemiol 20(3):204–211 Gram IT, Braaten T, Lund E, Marchand LL, Weiderpass E (2009) Cigarette smoking and risk of colorectal cancer among Norwegian women. Cancer Causes Control 20:895–903 WHO Global Status Report on Alcohol (2004) World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Geneva. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/ global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2010 World Health Organization ‘The Demographics of Tobacco’ Table. http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas40.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2010 Slattery ML, Potter JD, Duncan DM, Berry TD (1997) Dietary fats and colon cancer: assessment of risk associated with specific fatty acids. Int J Cancer 73(5):670–677 Vinikoor LC, Satia JA, Schroeder JC, Millikan RC, Martin CF, Ibrahim J, Sandler RS (2009) Associations between trans fatty acid consumption and colon cancer among Whites and African 123 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. Americans in the North Carolina Colon Cancer Study I. Nutr Cancer 61:427–436 Theodoratou E, McNeill G, Cetnarskyj R, Farrington SM, Tenesa A et al (2007) Dietary fatty acids and colorectal cancer: a case– control study. Am J Epidemiol 166:181–195 O’Keefe SJD, Chung D, Mahmoud N, Sepulveda AR, Manafe M, Arch J, Adada H, van der Merwe T (2007) Why do African Americans get more colon cancer than native Africans? J Nutr 137:175S–182S Speedy AW (2003) Global production and consumption of animal source foods. J Nutr 133:4048S–4053S Chao A, Thun MJ, Connell CJ, McCullough ML, Jacobs EJ, Flanders WD et al (2005) Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA 293:172–182 Norat T, Bingham S, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Mazuir M, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Clavel F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Kesse E, Boeing H, Bergmann MM, Nieters A, Linseisen J, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Tountas Y, Berrino F, Palli D, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bas Bueno-de-Mesquita H, Peeters PHM, Engeset D, Lund E, Skeie G, Ardanaz E, González C, Navarro C, Quirós JR, Sanchez MJ, Berglund G, Mattisson I, Hallmans G, Palmqvist R, Day NE, Khaw K, Key TJ, San Joaquin M, Hémon B, Saracci R, Kaaks R, Riboli E (2005) Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(12):906–916 Tiemersma EW, Kampman E, Bueno de Mesquita HB, Bunschoten A, van Schothorst EM, Kok FJ et al (2002) Meat consumption, cigarette smoking, and genetic susceptibility in the etiology of colorectal cancer: results from a Dutch prospective study. Cancer Causes Control 13:383–393 de Vogel S, Dindore V, van Engeland M, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, Weijenberg MP (2008) Dietary folate, methionine, riboflavin, and vitamin B-6 and risk of sporadic colorectal cancer. J Nutr 138:2372–2378 Schatzkin A, Mouw T, Park Y, Subar AF, Kipnis V, Hollenbeck A, Leitzmann MF, Thompson FE (2007) Dietary fiber and wholegrain consumption in relation to colorectal cancer in the NIHAARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 85:1353–1360 Voorrips LE, Goldbohm RA, van Poppel G, Sturmans F, Hermus RJJ, van den Brandt PA (2000) Vegetable and fruit consumption and risks of colon and rectal cancer in a prospective cohort study: the Netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer. Am J Epidemiol 152:1081–1092 Steinmetz KA, Kushi LH, Bostick RM, Folsom AR, Potter JD (1994) Vegetables, fruit, and colon cancer in the Iowa women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol 139:1–15 Zaridze D, Filipchenko V, Kustov V et al (1993) Diet and colorectal cancer results of two case-control studies in Russia. Eur J Cancer 29A:112–115 Bingham SA, Day NE, Luben R et al (2003) Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): an observational study. Lancet 361:1496–1501 Peters U, Sinha R, Chatterjee N et al (2003) Dietary fibre and colorectal adenoma in a colorectal cancer early detection programme. Lancet 361:1491–1495 Katalinic A, Raspe H, Waldmann A (2009) Positive family history of colorectal cancer––use of a questionnaire. Z Gastroenterol 47(11):1125–1131 Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, Burt RW (2010) Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology 138(6): 2044–2058 Lynch HT, Chapelle A (2003) Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 348:919–932 Al-Jaberi TM, Yaghan R, El-Heis H (2003) Colorectal cancer in young patients under 40 years of age: comparison with old Oncol Rev (2011) 5:5–11 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. patients in a well defined Jordanian population. Saudi Med J 24(8):871–874 Soliman AS, Bondy ML, Levin B, El-Badawi S, Khaled H, Hablas A, Ismail S, Adly M, Mahgoub KG, McPherson S, Beasley RP (1998) Familial aggregation of colorectal cancer in Egypt. Int J Cancer 77:811–816 Soliman AS, Bondy ML, El-Badawy SA, Mokhtar N, Eissa S, Bayoumy S, Seifeldin IA, Houlihan PS, Lukish JR, Watanabe T, On On Chan A, Zhu D, Amos CI, Levin B, Hamilton SR (2001) Contrasting molecular pathology of colorectal carcinoma in Egyptian and Western patients. Brit J Cancer 85(7):1037–1046 Isbister WH (1992) Colorectal cancer below age 40 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Aust N Z J Surg 62(6):468–472 Wei SC, Wang MH, Shieh MC, Wang CY, Wong JM (2002) Clinical characteristics of Taiwanese hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer kindreds. J Formos Med Assoc 101(3):206–209 Hall NR, Bishop DT, Stephenson BM, Finan PJ (1996) Hereditary susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Relatives of early onset cases are particularly at risk. Dis Colon Rectum 39(7):739–743 11 55. Bacolod MD, Schemmann GS, Giardina SF, Paty P, Notterman DA, Barany F (2009) Emerging paradigms in cancer genetics: some important findings from high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array studies. Cancer Res 69(3):723–727 56. Bener A, El Ayoubi HR, Chouchane L, Ali AI, Al-Kubaisi A, Al-Sulaiti TeebiAS (2009) Impact of consanguinity on cancer in a highly endogamous population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10(1):35–40 57. Kolahdoozan S, Sadjadi A, Radmard AR, Khademi H (2010) Five common cancers in Iran. Arch Iran Med 13(2):143–146 58. Dudley-Brown S, Freivogel M (2009) Hereditary colorectal cancer in the gastroenterology clinic: How common are at-risk patients and how do we find them? Gastroenterol Nurs 32(1):8–16 59. Brown ML, Goldie SJ, Draisma G, Harford J, Lipscomb J (2006) Health service interventions for cancer control in developing countries (Chap 29). In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P (eds) Disease control priorities in developing countries, 2nd edn. World Bank, Washington (DC) 123