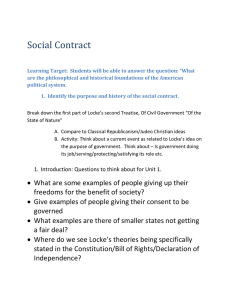

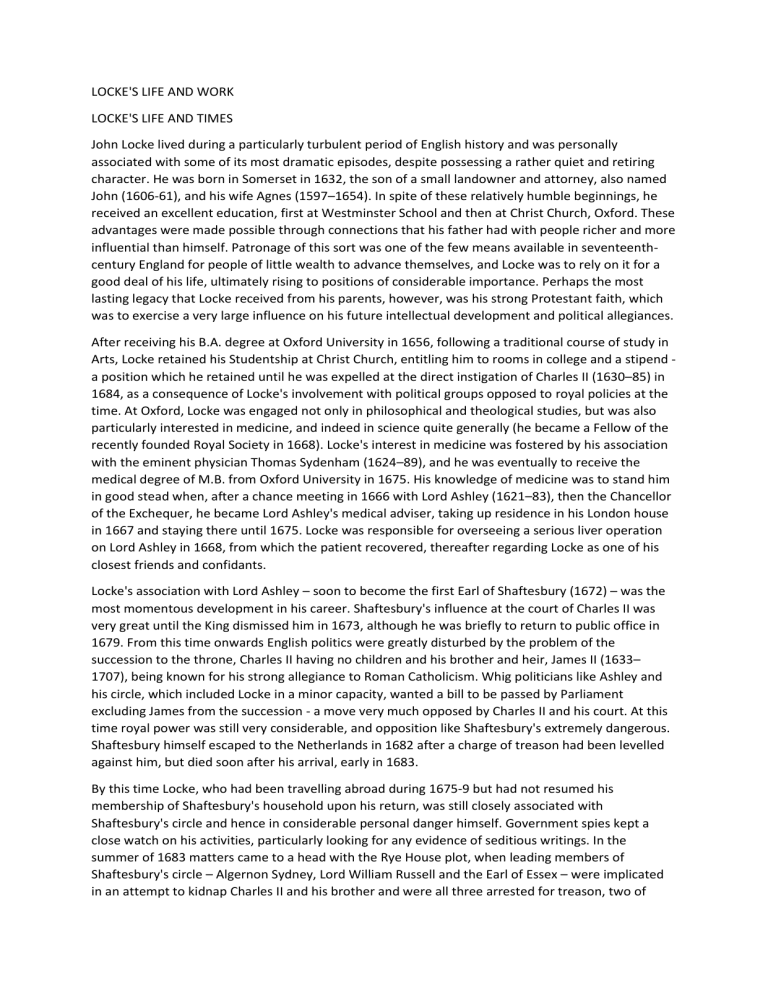

LOCKE'S LIFE AND WORK LOCKE'S LIFE AND TIMES John Locke lived during a particularly turbulent period of English history and was personally associated with some of its most dramatic episodes, despite possessing a rather quiet and retiring character. He was born in Somerset in 1632, the son of a small landowner and attorney, also named John (1606-61), and his wife Agnes (1597–1654). In spite of these relatively humble beginnings, he received an excellent education, first at Westminster School and then at Christ Church, Oxford. These advantages were made possible through connections that his father had with people richer and more influential than himself. Patronage of this sort was one of the few means available in seventeenthcentury England for people of little wealth to advance themselves, and Locke was to rely on it for a good deal of his life, ultimately rising to positions of considerable importance. Perhaps the most lasting legacy that Locke received from his parents, however, was his strong Protestant faith, which was to exercise a very large influence on his future intellectual development and political allegiances. After receiving his B.A. degree at Oxford University in 1656, following a traditional course of study in Arts, Locke retained his Studentship at Christ Church, entitling him to rooms in college and a stipend a position which he retained until he was expelled at the direct instigation of Charles II (1630–85) in 1684, as a consequence of Locke's involvement with political groups opposed to royal policies at the time. At Oxford, Locke was engaged not only in philosophical and theological studies, but was also particularly interested in medicine, and indeed in science quite generally (he became a Fellow of the recently founded Royal Society in 1668). Locke's interest in medicine was fostered by his association with the eminent physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–89), and he was eventually to receive the medical degree of M.B. from Oxford University in 1675. His knowledge of medicine was to stand him in good stead when, after a chance meeting in 1666 with Lord Ashley (1621–83), then the Chancellor of the Exchequer, he became Lord Ashley's medical adviser, taking up residence in his London house in 1667 and staying there until 1675. Locke was responsible for overseeing a serious liver operation on Lord Ashley in 1668, from which the patient recovered, thereafter regarding Locke as one of his closest friends and confidants. Locke's association with Lord Ashley – soon to become the first Earl of Shaftesbury (1672) – was the most momentous development in his career. Shaftesbury's influence at the court of Charles II was very great until the King dismissed him in 1673, although he was briefly to return to public office in 1679. From this time onwards English politics were greatly disturbed by the problem of the succession to the throne, Charles II having no children and his brother and heir, James II (1633– 1707), being known for his strong allegiance to Roman Catholicism. Whig politicians like Ashley and his circle, which included Locke in a minor capacity, wanted a bill to be passed by Parliament excluding James from the succession - a move very much opposed by Charles II and his court. At this time royal power was still very considerable, and opposition like Shaftesbury's extremely dangerous. Shaftesbury himself escaped to the Netherlands in 1682 after a charge of treason had been levelled against him, but died soon after his arrival, early in 1683. By this time Locke, who had been travelling abroad during 1675-9 but had not resumed his membership of Shaftesbury's household upon his return, was still closely associated with Shaftesbury's circle and hence in considerable personal danger himself. Government spies kept a close watch on his activities, particularly looking for any evidence of seditious writings. In the summer of 1683 matters came to a head with the Rye House plot, when leading members of Shaftesbury's circle – Algernon Sydney, Lord William Russell and the Earl of Essex – were implicated in an attempt to kidnap Charles II and his brother and were all three arrested for treason, two of them subsequently being executed. Locke, though not directly involved in this conspiracy, was now even more under suspicion, and escaped to the Netherlands in September 1683. From here he did not return to England until 1689. Following the Revolutionary Settlement of 1688, which removed James II from the throne after a disastrous reign of three years, the monarchy passed jointly to the Dutch Prince of Orange, William (1650–1702), and his wife Mary (1662–94), who were James II's nephew and daughter. With the reign of the Protestant William and Mary began the long period of Whig ascendancy in English politics, a regime very much in tune with Locke's own political and religious orientations. During his last years, from his return to England in 1689 to his death in 1704, Locke enjoyed public esteem and royal favour, in addition to great intellectual fame as the author of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which was published late in 1689. He performed a number of official duties, notably as a Commissioner of the Board of Trade, though his greatest desire was to pursue his literary and intellectual interests, including a good deal of correspondence. After some years of failing health, Locke died, aged 72, at the Essex home of Sir Francis and Lady Masham, a wealthy family with whom he had resided since 1692. Locke never married and had no children of his own, although he was fond of them and was influential in promoting more humane and rational attitudes towards their upbringing and education – never forgetting, it seems, the severe treatment he had received at Westminster School. In character he was somewhat introverted and hypochondriacal, but he by no means avoided company. He enjoyed good conversation but was abstemious in his habits of eating and drinking. He was a prolific correspondent and had a great many friends and acquaintances, on the continent of Europe as well as in Britain and Ireland. If there was a particular fault in his character, it was a slight tetchiness in response to criticism of his writings, even when that criticism was intended to be constructive. Though academic in his cast of mind, Locke was strongly moved by his political and religious convictions - especially by his concern for liberty and toleration - and had the good fortune to live at a time when there was no great divide between the academic pursuit of philosophical interests and the public discussion and application of political and religious principles. He thus happily lived to see some of his most strongly held intellectual convictions realised in public policy, partly as a consequence of his own writings and involvement in public affairs. THE STRUCTURE OF THE ESSAY AND ITS PLACE IN LOCKE'S WORK Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which was first published in full in December 1689, was undoubtedly his greatest intellectual achievement. He had been working on it off and on since the early 1670s, but most intensively during his period of exile in the Netherlands between 1683 and 1689. He continued to revise it after its first appearance, supervising three further editions of it in his remaining years. The fourth edition of 1700 accordingly represents his final view, and is the version most closely studied today. The Essay is chiefly concerned with issues in what would today be called epistemology (or the theory of knowledge), metaphysics, the philosophy of mind and the philosophy of language. As its title implies, its purpose is to discover, from an examination of the workings of the human mind, just what we are capable of knowing and understanding about the universe we live in. Locke's answer is that all the materials of our understanding come from our 'ideas' – both of sensation and of reflection (that is, of 'outward' and ‘inward' experience, respectively) - which are worked upon by our powers of reason to produce such 'real' knowledge as we can hope to attain. Beyond that, we have other sources of belief – for instance, in testimony and in revelation – which may afford us probability and hence warrant our assent, but do not entitle us to certainty. Given these concerns, we can readily understand the overall structure of the Essay, which is divided into four books. Book I, Of Innate Notions', is devoted to an attack on the advocates of innate ideas, who held that much of our knowledge is independent of experience. In Book II, 'Of Ideas', Locke attempts to explain in some detail how sensation and reflection can in fact provide all the ‘materials' of our understanding, even insofar as it embraces such relatively abstruse ideas as those of substance, identity and causality, which many of Locke's opponents took to be paradigmatically innate. In Book III, 'Of Words', Locke presents his account of how language both helps and hinders us in the communication of our ideas. Without such communication we could not hope to achieve mutual understanding, given Locke's view of the origins of our ideas in widely varying individual experience. Finally, in Book IV, 'Of Knowledge and Opinion', Locke discusses the ways in which processes of reason, learning and testimony operate upon our ideas to produce certain knowledge and probable belief, and at the same time he tries to locate the proper boundary between the province of reason and experience on the one hand and that of revelation and faith on the other. Locke's view of our intellectual capacities is clearly a modest one. At the same time, he held a strong personal faith in the truth of Christian religious principles, which may seem to conflict with the mildly sceptical air of his epistemological doctrines. In fact, he himself perceived no conflict here – unlike some of his contemporary critics – though he did regard his modest view of our intellectual capacities as providing a strong motive for religious toleration. Reason, he thought, does not conflict with faith, but in questions of faith to which reason supplies no answer it is both irrational and immoral to insist on conformity of belief. We have it on record, indeed, that what originally motivated Locke to pursue the inquiries of the Essay was precisely a concern to settle how far reason and experience could take us in determining moral and religious truths. Locke's concern with morality and religion, both intimately bound up with questions of political philosophy in the seventeenth century, was one which dominated his thinking throughout his intellectual and public career. His earliest works, unpublished in his own lifetime, were the Two Tracts on Government (1660 and 1661) and the Essays on the Law of Nature (1664), both written in Latin but now available in English translation. The position on issues of political liberty and religious toleration that he adopted in those early works was, however, considerably more conservative than the one that he later came to espouse, following his association with Shaftesbury, and made famous in his Letter on Toleration and Two Treatises of Government (both published anonymously in 1689, the former in Latin and the latter in English). The Second Treatise explicitly recognises the right of subjects to overthrow even a legitimately appointed ruler who has abused his trust and tyrannises his people – a doctrine which would almost certainly have led to Locke's being accused of sedition had the manuscript been discovered by government spies. The First Treatise was an extended attack upon an ultra-royalist tract written by Sir Robert Filmer (d. 1653), entitled Patriarcha (published 1680), in which the divine right of kings was defended as proceeding from the dominion first granted by God to Adam. Algernon Sydney (1622–83), one of the Rye House plot conspirators, had been convicted of sedition partly on the strength of a manuscript he had written attacking Filmer's work, so one can well understand Locke's secrecy and caution in the years preceding his flight to the Netherlands. In addition to the works already mentioned, Locke published a good many other writings, notably on religious and educational topics. Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) was the product of advice he had provided in correspondence, over a number of years, to his friends Edward and Mary Clarke concerning the upbringing of their children. This work went into many editions, proving to be very popular and influential with more enlightened parents for a long time to come. Locke's interest in the intellectual development of children is also plain to see in the Essay itself, where it has a direct relevance to his empiricist principles of learning and concept-formation. Locke's explicitly religious writings include The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695) and the learned and lengthy Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St Paul (published posthumously, 1705-7). He also wrote on economic and monetary issues connected with his various involvements in public and political affairs. He even found time to compose a critique of the theories of the French philosopher Nicholas Malebranche (1638–1715, a contemporary developer of Cartesian philosophy), entitled An Examination of P. Malebranche's Opinion of Seeing All Things in God. Other items included in his collected Works, which have run to many editions, are extensive replies to Edward Stillingfleet (1635–99), bishop of Worcester, answering hostile criticisms raised by the latter against the Essay, and a long piece entitled 'Of the Conduct of the Understanding', which was originally intended for inclusion in a later edition of the Essay. From this brief survey of Locke's work, we can see that although his most important writings were published in his fifties and sixties, during a comparatively short interval beginning in his most momentous year of 1689, his thoughts were the product of a very long period of gestation stretching back at least thirty years before that. It is quite fair to say, however, that the Essay was the cornerstone of all his intellectual activity, providing the epistemological and methodological framework for all his other views and enterprises. And although we are particularly fortunate in having a remarkably complete collection of Locke's original manuscripts and letters as well as his many other publications, it is on the Essay that his reputation as the greatest English philosopher stands. Written in English at a time when English prose style was at the peak of its vigour, and Latin had begun to wane as the language of intellectual communication, it is both a literary and a philosophical masterpiece, which can still be read today for pleasure as well as enlightenment. Although in reading the Essay it is helpful to know something of the historical and intellectual background to its composition, it is a remarkable testimony to its durability and stature as a work of philosophy, as well as to its appeal as a work of literature, that it can still be taken up and studied with profit and pleasure, three hundred years after its first appearance, by anyone susceptible to the intellectual curiosity that its pages provoke.