Ralegh's "Hellish Verses" and the "Tragicall Raigne of Selimus"

advertisement

Ralegh's "Hellish Verses" and the "Tragicall Raigne of Selimus"

Author(s): Jean Jacquot

Source: The Modern Language Review , Jan., 1953, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Jan., 1953), pp. 1-9

Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3719161

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Humanities Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Modern Language Review

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

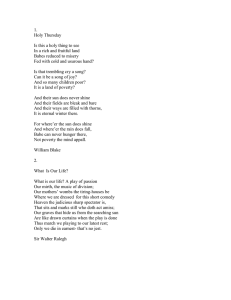

VOL UME XLVIII JANUARY 1953 NUMBER 1

RALEGH'S 'HELLISH VERSES' AND THE 'TRAGICALL

RAIGNE OF SELIMUS'

Biographers and critics have paid little attention to the manuscri

attributed to Sir Walter Ralegh, belonging to the collection of the Ma

and published in a Report of the Historical Manuscripts Commission.l

we have to face in our attempt to interpret the poem and explain its

complex that it is necessary to reproduce the full text:

1603 Certaine hellish verses devysed by that Atheist and traitor Ral

said viz:

When first this circkell round, this building fayre,

some god tooke out of this confused masse

what god I do not know nor greatly care

then every one his owne director was,

then war was not nor ritches was not knowne

and no man said then this or that ys my owne

the plowman with a furrowe did not marke

how far his great possessions they did reache

the earth knew not the shore nor the sea the barke

nor souldiers dared not the battered breach 10

nor trumpets loud tantara then did teache

they neided then nothing of whom to stand

but after Ninus warlicke Bellus sonne

with uncouth armoure did the earth array

then first the sacred name of King begann

and things that were as common as the day

did yeld themselves and likewise did obey

and with a common muttering discontent

gave that to tyme which tyme cannot prevent.

Then som sage man amonge the vulgarr 20

knowing that lawes could not in quiet dwell

unles the[y] were observed did first devyse

the name of god, religion, heaven and hell

and gaine of paines and fair rewardes to tell

paines for theis that did neglecte the lawe

rewardes for him that lived in quiet awe

whereas in deid they were mere fictions

and if they were not yet (I thinke) they were

and those religious observationes

onely bugberes to keepe the worlde in feare 30

and make them quietly the yoke to bere

so that religion of itself a fable

was onely found to make that peaceable

herein especially comes the foolish names

of father mother brother and such lyke.

But whosoe well his cogitations frames

shall onely fynd they were but for to strick

into our minds as tever [sic] kind of lyke

1 MSS. of the Marquis of Bath at Longleat I am indebted to Mr I. R. F. Cal

(Wilts), vol. ii, pp. 52-3. V. T. Harlow quotes transcribing the text at a time

a few lines of the poem in his edition of The access to the Reports of the H

Discoverie of Guiana (1928), Introd. pp. xxxiii-iv. making useful suggestions.

M.L.R.

XLVIII

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1

2 Ralegh's 'Hellish Verses' and the 'Tragicall Raigne of Selimus'

regard of some for shew, for feare, for shame l

indeid I must confes they were not bad 40

because they keep the baser sort in fere

but we whose myndes with noble thoughts ar clad

whose body doth a ritch spirit bere

which is not knowne byt flyethe everywhere

why should we seeke to make that soule a slave

to which dame Nature such large freedom gave.

Amongst us men there is some difference

as affections termeth us be it good or ill

as he that doth his father recompence

(liffers from him which doth his father kill 50

and yet I think, think others what they will

that paradice when death doth give them rest

shall have a good as part even as the best l

and that is just nothing for as I suppose

in deathes void kingdom rules eternall night

secure of evill secure of foes

where nothing doth the wyched soule affright

then since in death nothing doth us befall

here while I live I will have a fetch at all.

Finis R. W. alias W. RAWLEY

Endorsed Verces written by Sir Walter Rawleye 1603

The date and the title of the manuscript give us a clear idea of the use

to be made of such lines. Ralegh was being accused of collusion with S

taking part in a plot to dethrone James I. It hardly needs to be repe

those days any attack against authorized religion was a crime agains

The connexion between the theological and the political aspects of th

appears clearly in the wording of the official inquiry on the opinions of

his circle held at Cerne in March 1594.1 Ralegh had already been me

police reports as an associate of the 'atheist' Marlowe2 and persistent

his impiety had circulated. The evidence brought to light by the C

mission was of a rather compromising nature, at least by Elizabethan

Yet he was not prosecuted: though he was no longer a favourite, the Que

want his utter ruin. But in 1603 the situation was different, his ene

determined to make full use of his reputation as an unbeliever. Durin

the Attorney-General Sir Edward Coke was to fling the accusation of ath

betrayal in his face, thus making up by verbal violence for the weakness

ments. The same attacks are to be found again and again in lampoons

the time of his fall by envious poetasters.3 There exists a second manusc

of the 'hellish verses' which is practically identical with the Longl

bears the same date and was obviously written with the same purp

crediting Ralegh on the eve of his trial.4 The Longleat collection al

1 Harleian MSS. 6849, ff. 183 seq., reproduced same as in the Longleat copy. S

in Danchin, 'Etudes critiques sur Marlowe' 'finis R. W. alias W. Rawley'. The

(Revue germanique, 1913, pp. 566-87), document mentioned in the heading, but in

vi. ment ('verses sayed to be written by Walter

2 Harleian MSS. 6848, f. 190; Danchin, Rawley knight 1

document iv. hand. Like the Longleat copy, it has paradice

3 See T. N. Brushfield, A Bibliography of for parricides (1. 52) and

Ralegh (London, 1908), pp. 146-8. mistake: factions for fictions (1. 27). It gives a

4 British Museum, Add. MSS. 32092, f. 201. better reading of 11. 37 (strike), 38 (tender instead

The title ('Certaine hellish verses', etc.) is the of tever), 53 (as good a part, but even is omitted).

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEAN JACQUOT 3

a letter from Robert Cecil to Sir Mich

with a postscript summing up the Minist

Ralegh, and others:

Whatever you hear about innocency kno

Sir Walter Ralegh his contempts are high, h

Robert Cecil himself, as an adversary of

of such a compromising poem.

The problem at first seemed simply t

were really the work of Ralegh or a forg

familiar and recalled a speech in an ano

Tragicall Raigne of Selimus, published

confirmed the impression: but for a few

best of our knowledge, the resemblance

passage in Selimus, the central part of

character of the play:

When first this circled round, this

Some God tooke out of the confused masse,

(What God I do not know, nor greatly care)

Then euery man of his owne dition was,

And euery one his life in peace did passe.

Warre was not then, and riches were not knowne, 310

And no man said, this, or this, is mine owne. |

The plough-man with a furrow did not marke

How farre his great possessions did reach:

The earth knew not the share, nor seas the barke.

The souldiers entred not the battred breach,

Nor trumpets the tantara loud did teach.

There needed them no iudge, nor yet no law,

Nor any King of whom to stand in awe.

But after Ninus, warlike Belus, sonne,

The earth with vnknowne armour did warray, 320

Then first the sacred name of King begunne:

And things that were as common as the day,

Did then to set possessours first obey

Then they establisht lawes and holy rites,

To maintaine peace, and gouerne bloodie fights. I

Then some sage man, aboue the vulgar wise,

Knowing that lawes could not in quiet dwell,

Vnlesse they were observed: did first deuise

The names of Gods, religion, heauen, and hell;

And gan of paines, and faind rewards to tell: 330

Paines for those men which did neglect the law,

Rewards, for those that liu'd in quiet awe.

Whereas indeed they were meere fictions,

And if they were not, Selim thinkes they were:

And these religious obseruations,

Onely bug-beares to keepe the world in feare,

And make men quietly a yoake to beare.

So that religion of it selfe a bable,

Was onely found to make vs peaceable. I

1 MSS. of the Marquis of Bath, vol. ii, pp. x arrest John Shelbury, one of th

and 51. On p. 54 there is a letter from Sir Walter Ralegh's estate, 'bound for me f

Ralegh to Sir Michael Hicks, asking him not to

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4 Ralegh's 'Hellish Verses' and the 'Tragicall Raigne of Selimus'

Hence in especiall come the foolish names,

340

Of father, mother, brother, and such like:

For who so well his cogitation frames,

Shall finde they serue but onely for to strike

Into our minds a certaine kind of loue.

For these names too are but a policie,

To keepe the quiet of societie. [

Indeed I must confesse they are not bad,

Because they keepe the baser sort in feare:

But we, whose minde in heauenly thoughts is clad,

Whose bodie doth a glorious spirit beare,

That hath no bounds, but flieth euery where.

Why should we seeke to make that soule a slaue,

To which dame Nature so large freeldome gaue.

Amongst vs men, there is some difference.

Of actions tear7ned by vs good or ill:

350

As he that doth his father recompence,

Differs from him that coth his father kill.

And yet I thinke, thinke others what they will,

That Parricides, when death hath giuen tlem rest,

Shall have as good a part as the rest.

And thats iust nothing, for as I suppose

In deaths voyd kingdome raignes eternall night:

360

Secure of euill, and secure of foes,

Where nothing (loth the wicked man.affright,

No more than him that dies in doing right.

Then since in death nothing shall to vs fall,

Here while I liue, Ile haue a snatch at all.1

The Longleat MS. seems to be the work of a copyist w-ho did not fully understand

what he was reading. On the whole, the Selimus text is much better: it gives

a satisfactory reading of lines corrupt in the other text and does not deviate from

the rhyme royal structure, while there are four lines missing in the MS. Lines 309

and 365 in Selimus are omitted in the MS. (after 1. 4 and 1. 57) and 11. 317-18 are

contracted into one (1. 14). Lines 345-6 are also replaced by a single line, 1. 39,

expressing a rather different idea. Again 11. 18-19 in the MS. differ entirely from

the corresponding lines (324-5) in the play. The reader will also notice other variants

between the two texts, which cannot be explained by the negligence or the ignorance

of the transcriber. The Longleat MS. is not copied directly from the only known

edition of Selimus. Yet this may be the ultimate source of the MS. Corruptions of

the text can be explained by successive transcriptions. And important variants

may have been introduced in an effort to reconstitute the text from memory. On

the other hand it is not impossible that the Longleat scribe and the author of the

play had recourse to different versions of the same poem. In other words there are

two ways of accounting for the relation of the MS. to the play. Either some enemy

of Ralegh's lifted a passage spoken by a tyrant in a nearly forgotten play and gave

it as the authentic expression of Ralegh's opinions, or some impudent dramatist

obtained the text of an unpublished poem of Sir Walter's and inserted it in the

tragedy.

Selimus was published in 1594 and, in its final form, it cannot be anterior to

between the two versions and added bars in both

1 Scene ii, UI. 305-67. Reproduced from the

texts to separate the stanzas.

facsimile edition (Malone Society Reprints). We

have used italics to indicate the difference

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEAN JACQUOT 5

1591.1 A large part of the tragedy is i

predominates are in blank verse. But

a way that suggests the re-handling o

'hellish verses' seems to indicate that th

speech in which they are found is writt

stanza is used in other soliloquies of a de

are admirably suited to the situation.

without giving a detailed account of a

The First Part of the Tragicall raigne of

Wherein is showne how hee most vnnat

Baiazet, and preuailing therein, in the en

Also with the murthering of his two br

The historical Selimus who rebelled in 1

becomes a Senecan tyrant, taking th

placently revealing the darkness of his

justify the parricide he is about to co

function and certain lines-which wo

seem meant to underline the folly of th

principles and at the same time pays

having stated that pains and rewards

a rash and wilful way,

And if they were not, Selim think

In the 'hellish verses' we read:

and if they were not yet (I thinke) they were (1. 28)

which looks very much like a clumsy effort to eliminate the name of Selimus.

This seems to indicate fairly clearly that Ralegh's enemies used the text o

play. Yet a series of objections has to be considered. First, it must be adm

that vigour of thought, easiness and coherence of expression, absence of ve

and bombast, and even certain poetical qualities raise the passage under disc

above the rest of the tragedy, which is sorry stuff. Secondly, though the p

fits the dramatic situation, it is awkwardly introduced: Selimus declares that h

going to refute the arguments of the schools and fortify himself in his impiety,

seems hardly necessary judging by the sacrilegious fury of the words he h

proffered. Lastly, we must bear in mind that the author of Selimus carried plagi

further than most of his contemporaries, who were not as a rule over-scrupulo

that matter. He stole whole passages from the anonymous tragedy of Lo

including those that had already been borrowed by it from Spenser. Conseq

it is not unreasonable to suspect him of stealing a poem circulating in manuscri

It is true that this passage is more striking than anything else in the play

that the effect is not entirely due to the boldness of the ideas expressed. But t

is much in other scenes which, though rather dull and commonplace,, is nevert

addressed to the spectator's intelligence, not to his cruder emotions. And

interest of the modern reader is revived in one later scene (xxiii) where Sel

1 For a summary of the critical studies of the of Robert Greene (Oxford, 1905), vol. I, pp

play see The Cambridge History of English shows that there is little ground for ascribi

Literature, vol. v, pp. 84-8 and 134, and E. K. play to that dramatist.

Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, vol. iv, p. 46. 2 Bajazet's monologue, scene iii, for in

J. C. Collins, in his edition of the Plays and Poems 3 Lines 305-7, 333-4.

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 Ralegh's 'Hellish Verses' and the 'Tragicall Raigne of Selimus'

brother faces the tyrant who has sentenced him to death and predicts that the

usurper will have to account for his actions on the Day of Judgement. There is no

consistent moral or religious purpose behind the play, which ends with the triumph

of Selimus, and the promise of more horrible crimes in a second part, of which we

know nothing. But there is a deliberate contrast between these two scenes which,

to the reader at least, are the most impressive. And this tends to prove that they

were originally planned as parts of the same whole. On the other hand if we could

find models for, or traces of borrowings in, the 'hellish' passage its originality might

cease to surprise us, and it would be no longer necessary to account for its presence

in the play by the appropriation of a manuscript poem.

When the author wrote the first two stanzas, he obviously had in mind the

beginning of the Metamorphoses. It was one of the most popular classics, and

Arthur Golding's translation had further contributed to its diffusion. Verbal echoes

seem to indicate that he had Ovid's poem in front of him. The Latin poet, after

describing chaos, tells how a god changed it into an ordered universe (Bk. I, 11. 3-35).

It is easy to see, without quoting at length from the familiar text, that our author

summed up in three lines this passage on the origins of the world. In the rest of the

first stanza and the whole of the second, we find condensed two passages from Ovid's

description of the Golden Age (11. 89-102) and of the Iron Age (11. 125-43). It is

worth noticing, too, that Ovid gives a gloomy picture of a state of affairs where men

and women of the same kin slay and poison each other, where piety is defeated and

the son plots against his father's life (the very situation of the play). Then he

proceeds with the story of a race, bloodthirsty and contemptuous of the gods, born

of the rebellious giants. He tells of the cruel Lycaon, 'tyrant of Arcadia', who

mocks the people's prayers and doubts the divinity of Jupiter. And the story ends

with the destruction, in the Flood, of a corrupt humanity. Though we find no trace

of literal imitation, we are entitled to suppose that our author had these episodes

in mind when he made his tyrant, his parricide, speak of family ties as a ridiculous

convention, or when he lent him a Titanic mind, 'clad in heavenly thoughts',

a 'glorious spirit that hath no bounds'.

The legend of the Golden Age was closely related to the story of the Fall.

Theologians and jurists made frequent allusions to it when they explained that,

through the growth of vice and lust, laws and coercive institutions had become

necessary to maintain peace and order, and to protect society from tyrannical

rulers. Our author was, apparently, aware of this interpretation. And his treatment of ideas current in his time was affected by unexpectedly wide reading. Thus

he seems to have derived his knowledge of Ninus from a passage of The City of God

(Book IV, ch. 6) where St Augustine, quoting Justinius, establishes a sharp distinc-

tion between just kings and ruthless conquerors. As for the 'sage man above the

vulgar wise', who invented religion to 'keepe the baser sort in feare', I believe his

mo(lel is to be found in a fragment of a Greek poem which Sextus Empiricus

(Adversus mathematicos, ix, 54) attributes to Critias, the leader of the Thirty

Tyrants, and gives as an example of atheism.

An examination of the sources undoubtedly adds weight to the arguments which

tend to prove that the 'hellish verses' originally belonged to Selimus.l The dramatist

carefullly looked for texts which helped him to outline the thoughts of a tyrannical

I shall fully discuss, in Etudes anglaises, the sources of Selimus's monologue and their bearing

on the interpretation of the play.

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEAN JACQUOT

7

and impious warrior, and at the same time to suggest that Selimus used a very

specious way of reasoning. Selimus's speech sounds, as it should, like a diabolic

distortion of theology and orthodox political theory. This was exactly the sort of

document Ralegh's enemies required, to stir opinion against 'that atheist and

traitor'. It seems hard to believe that Ralegh wrote a poem just for the sake of

saying 'I am an atheist and a very wicked fellow'. If by any chance he wrote the

'hellish verses', it must have been in the mood of defiance and bitter irony which

inspired The Lie, at a time when he thought he had seen through the fictions on

which the order of society depended, but was also conscious of the extreme consequences, on the moral plane, of a denial of immortality. As a paradoxical way

of setting a problem, as a piece of grim humour in the vein of The Jew of Malta,

the existence of such a poem is not absolutely inconceivable.

Let us see, then, what evidence may be produced in favour of Ralegh's authorship. As far as form is concerned there is little, apart from the fact that he once

employed the rhyme royal stanza' and that some of his best known poems have

a similar stanza structure (ababcc). As for the content, the arguments can be

grouped under three headings.

(1) In the earlier part of his life, Ralegh listened complacently to aphorisms of

his associates, some of which closely resembled those of the 'hellish verses'. For

instance Marlowe-who is said to have read, some time before his death in 1593, an

'atheist lecture' to Ralegh2-spoke of Moses as a cunning leader for whom it was

easy 'being brought up in all the artes of the Egyptians to abuse the Jews being

a rude and grosse people'.3 This means that the author of Tamburlaine attributed

to this eminent Biblical figure a cunning similar to the pagan lawgiver Numa. We

may also notice that the lines

and those religious observationes

onely bugberes to keepe the worlde in feare

sound uncommonly like the words attributed to Marlowe by Baines: 'but almost

in every company he cometh he perswades men to Atheism willing them not to be

afeard of bugbeares and hobgoblins'.4 The words of Ralegh's brother, as reported

by Parson Ironside, also bear a strong resemblance to the 'hellish verses':

M. Carew Rawleigh demaunds of me what daunger he might incurr by suchI

speeches? whereunto I aunswered the wages of sin is death and he making liglht of

death as being common to all sinner and reightuous, I inferred further, that as that

liffe which is the gifte of God t[h]rough Jesus-Christ is liffe eternall: so that death whlilch

is properly the wage of sin, is death eternal, both of the bodye, and of the soile alsoe.

Soule quoth Mr Carewe Rawleigh what is that ?5

At that very moment Sir Walter joined in the discussion, questioning Ironside and

refuting his arguments for the existence of God and the soul. I am ready to admit

that Ralegh's critical attitude can be explained by his contempt for the parson's

scholastic formulae.6 But was it the part of a good Christian to choose the moment

In the translation of a short fragment of article, 'The History of the World and Ralegh's

zEschylus's Prometheus (History of the World, Skepticism' (Huntington Library Quarterly, 1939,

ii, vi, 4). no. 3), which is a capital contribution to the

2 Harl. IMSS. 6848, f. 190; Danchin, document study of Ralegh's

Iv. a certain consistency in Ralegh's use of sceptical

3 Harl. MSS. 6848, f. 185a; Danchin, docu- arguments. Yet

ment I. 4 Ibid. f. 185b. the discussion with Ironside, they come into play

5 Harl. MSS. 6849, f. 187b; Danchin, docu- in favour of unbelief, while twenty years

mlent vi. in the Preface of The History of the lWorld

6 As Mr E. A. Strathmann pointed out in an Pyrrhonism becom

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 Ralegh's 'Hellish Verses' and the 'Tragicall Raigne of Selimus'

when a parson was hard pressed by atheists to ask embarrassing questions? It is

true also that he put an end to the debate by wishing 'that grace might be said for

that quoth he is better than this disputation'. But did not Pyrrho recommend

that external respect for religious customs should be joined to scepticism of dogmas ?

Even so, it is difficult to say to what extent he shared the views of Marlowe or

Carew Ralegh; we must leave them the responsibility of their opinions and we can

only conclude that he was tolerant of such opinions, and listened to them with

interest.

(2) Much of the material upon which the author of the 'hellish verses' worked is

to be found also in the History of the World where it acquires, however, a different

significance. In his main work Ralegh expresses the view that the Golden Age of

the Ancients corresponded to the period following the Flood (and not preceding it

as in Ovid). Ambition and covetousness were still in their infancy, 'for while the

law of nature was the rule of man's life, they then fought for no larger territory

than themselves could compass and manure'.1 The authority of fathers and elders

was sufficient to keep them in peace. But with the growth of population vices also

increased, the need for order and obedience became greater than ever; then the

State and the laws had their beginning.2 This is the Christian version of the story.

Not only does he seek to conciliate the heathen myth with Biblical orthodoxy but

he insists on the idea that civil government is ordained by God.3 After describing

in general terms the emergence of state institutions, he devotes a whole chapter

(I, x) to the first Babylonian kings. After the Flood, he says, Nimrod was the first

to enjoy sovereignty. This king is not mentioned in the verses, but his successors

were Belus and Ninus according to Ralegh who discusses at length their right order

of succession and gives the etymology of Belus (connecting it with Baal which

means a war chief) to explain the warlike character of these kings. I was at one

time impressed by the fact that both Ralegh and the author of the verses were

interested in the origins of the Babylonian monarchy, but since the passage of

The City of God on Ninus was easy of access to the author of Selimus and served his

dramatic purpose in the monologue, I do not think this argument can be advanced

in favour of Ralegh's authorship.

As for that 'sage man' who 'did first devyse the name of god, religion, heaven and

hell', we also find his equivalent in the History of the World. Numa Pompilius,

'a peaceable man, and seeming very religious in his kind', 'brought the rude

people... to some good civility, and a more orderly fashion of life. This he effected

by filling their heads with superstition. 4 There is nothing unorthodox in Ralegh's

use of this well-known story. At most we could note that he abstains from condemning Numa as a politic atheist, and seems to think that the stratagem produced

good results. But Numa was a pagan, and Ralegh does not say that all religion is

superstition.4 He gives several examples, besides that of Numa, of statesmen and

priests using religious creeds to political ends; but these are all heathens, not

worshippers of Jehovah. To conclude, none of the arguments under this heading

has much weight. There is nothing unusual about the erudition of the verses, and

the range of Ralegh's knowledge is so vast, his subject so universal, that we should

not be surprised to find in his main work the equivalent of the mythical and

historical allusions in the Selimus passage. Besides, as is well known, there is

1 i, ix, 3; vol. I, p. 347 of The Works (Oxford, 3 Ibid. pp. 342-3.

1829). 4 i, xxvii, 6; Works, vol. iv, pp. 779-80.

2 I, ix, 1; ibid. pp. 339-41.

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

9

JEAN JACQUOT

nothing contrary to religion in The History of the World. To say that, his convictions

having changed, he gave a Christian significance, in the History, to a theme which

he had treated, in the verses, from the point of view of a sceptic, is entirely

speculative.

(3) At least it can be said that, while he constantly refers to the intervention of

Providence in his account of human events, we find here and there, in the History,

signs of his knowledge, and even appreciation, of Machiavelli. Of such a nature is

his account of Numa. And in The Cabinet Council, a treatise written in the latter

part of his life, we find some of the Machiavellian axioms which in those days

disturbed the consciences of so many people. 'Whoso laboureth to be good shall

perish living among men generally evil.' A Prince may be 'constrained for defence

of his state to proceed contrary to promise, charity, virtue',1 and the 'hellish verses'

contain opinions, concerning the 'vulgar' and the use of fear for the maintenance

of order, which closely resemble some of Ralegh's maxims. 'The vulgar sort is

generally variable, rash, hardy, and void of judgment.' The Prince should win the

love of his subjects; nevertheless 'the condition of men is such as cannot be restrained by shame, yet it is to be commanded by fear' and 'Men respect less whom

they love than whom they fear'.2

To sum up: the first and third groups of arguments tend to prove that the

rumours of his impiety, during the earliest part of his life, were not entirely without

foundation. His attitude may have just been one of free inquiry, and of impatience

with conventional ways of thinking. Contemporaries were shocked, all the more so

because some of his associates indulged in blasphemy and one of them at least,

Marlowe, in anti-religious propaganda. Besides, he was in his later life a serious

student of Machiavelli, some of whose maxims seem to clash with his conception

of history. That he was conscious of a contradiction and felt the need of a conm-

promise may be seen in The Prince, or MJaxims of State, where he is anxious to warn

Prince Henry, for whom the work was intended, that it was better to know some

of Machiavelli's axioms than to put them into practice. Yet The Cabinet Council is

the more important of his Machiavellian essays, and he seems to write there with

less caution and restraint. There was certainly alwvays in his thought an undercurrent of political realism, of the sort which is expressed in an extreme and

caricatural form in the 'hellish verses'. This does not mean of course that he wrote

them but that his authorship would not be entirely unthinkable if there existed an

external evidence in its favour, and the verses had not, as they have, a dramat

significance which obliges us to consider them as originally belonging to the play.

The fact that they could be used against Ralegh, and that we had to sift careful

the evidence before we could safely reject his authorship tends to show that there

was an even closer connexion than we thought between 'atheism' on the stage an

in philosophical circles, between the 'Machiavellianism' of the theatre and that

Elizabethan politics. An examination of the sources of the verses, apart from it

interest to the student of Selimus, also indicates that the tyrant's speech cannot be

dismissed as just a piece of dramatic sensationalism. The playwright, whatever h

intentions may have been, used ideas that were in the air, and the passage can add,

in an indirect way, to our knowledge of the serious thinking of the time.

JEAN JACQUOT

PARIS

1 The Cabinet Council (vol. viii of The Works), ch. xxiv, pp. 103, 105.

2 Ibid. ch. xv, p. 58; ch. xvi, p. 59; ch. xxiv, p. 104.

This content downloaded from

212.154.85.153 on Tue, 15 Dec 2020 18:40:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms