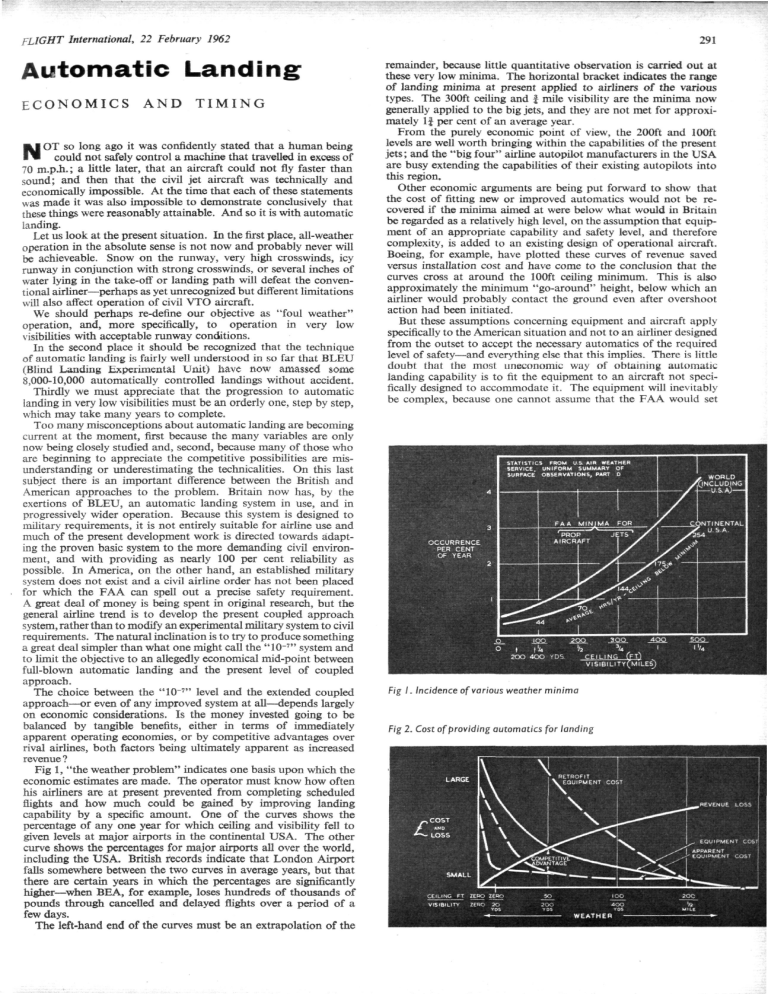

FLIGHT International, 22 February 1962 Automatic Landing ECONOMICS AND TIMING OT so long ago it was confidently stated that a human being N could not safely control a machine that travelled in excess of 70 m.p.h.; a little later, that an aircraft could not fly faster than sound; and then that the civil jet aircraft was technically and economically impossible. At the time that each of these statements was made it was also impossible to demonstrate conclusively that these things were reasonably attainable. And so it is with automatic landing. Let us look at the present situation. In the first place, all-weather operation in the absolute sense is not now and probably never will be achieveable. Snow on the runway, very high crosswinds, icy runway in conjunction with strong crosswinds, or several inches of water lying in the take-off or landing path will defeat the conventional airliner—perhaps as yet unrecognized but different limitations will also affect operation of civil VTO aircraft. We should perhaps re-define our objective as "foul weather" operation, and, more specifically, to operation in very low visibilities with acceptable runway conditions. In the second place it should be recognized that the technique of automatic landing is fairly well understood in so far that BLEU (Blind Landing Experimental Unit) have now amassed some 8,000-10,000 automatically controlled landings without accident. Thirdly we must appreciate that the progression to automatic landing in very low visibilities must be an orderly one, step by step, which may take many years to complete. Too many misconceptions about automatic landing are becoming current at the moment, first because the many variables are only now being closely studied and, second, because many of those who are beginning to appreciate the competitive possibilities are misunderstanding or underestimating the technicalities. On this last subject there is an important difference between the British and American approaches to the problem. Britain now has, by the exertions of BLEU, an automatic landing system in use, and in progressively wider operation. Because this system is designed to military requirements, it is not entirely suitable for airline use and much of the present development work is directed towards adapting the proven basic system to the more demanding civil environment, and with providing as nearly 100 per cent reliability as possible. In America, on the other hand, an established military system does not exist and a civil airline order has not been placed for which the FAA can spell out a precise safety requirement. A great deal of money is being spent in original research, but the general airline trend is to develop the present coupled approach system, rather than to modify an experimental military system to civil requirements. The natural inclination is to try to produce something a great deal simpler than what one might call the "10-"' system and to limit the objective to an allegedly economical mid-point between full-blown automatic landing and the present level of coupled approach. The choice between the "10"'" level and the extended coupled approach—or even of any improved system at all—depends largely on economic considerations. Is the money invested going to be balanced by tangible benefits, either in terms of immediately apparent operating economies, or by competitive advantages over rival airlines, both factors being ultimately apparent as increased revenue ? Fig 1, "the weather problem" indicates one basis upon which the economic estimates are made. The operator must know how often his airliners are at present prevented from completing scheduled flights and how much could be gained by improving landing capability by a specific amount. One of the curves shows the percentage of any one year for which ceiling and visibility fell to given levels at major airports in the continental USA. The other curve shows the percentages for major airports all over the world, including the USA. British records indicate that London Airport falls somewhere between the two curves in average years, but that there are certain years in which the percentages are significantly higher—when BEA, for example, loses hundreds of thousands of pounds through cancelled and delayed flights over a period of a few days. The left-hand end of the curves must be an extrapolation of the 291 remainder, because little quantitative observation is carried out at these very low minima. The horizontal bracket indicates the range of landing minima at present applied to airliners of the various types. The 300ft ceiling and £ mile visibility are the minima now generally applied to the big jets, and they are not met for approximately 1} per cent of an average year. From the purely economic point of view, the 200ft and 100ft levels are well worth bringing within the capabilities of the present jets; and the "big four" airline autopilot manufacturers in the USA are busy extending the capabilities of their existing autopilots into this region. Other economic arguments are being put forward to show that the cost of fitting new or improved automatics would not be recovered if the minima aimed at were below what would in Britain be regarded as a relatively high level, on the assumption that equipment of an appropriate capability and safety level, and therefore complexity, is added to an existing design of operational aircraft. Boeing, for example, have plotted these curves of revenue saved versus installation cost and have come to the conclusion that the curves cross at around the 100ft ceiling minimum. This is also approximately the minimum "go-around" height, below which an airliner would probably contact the ground even after overshoot action had been initiated. But these assumptions concerning equipment and aircraft apply specifically to the American situation and not to an airliner designed from the outset to accept the necessary automatics of the required level of safety—and everything else that this implies. There is little doubt that the most uneconomic way of obtaining automatic landing capability is to fit the equipment to an aircraft not specifically designed to accommodate it. The equipment will inevitably be complex, because one cannot assume that the FAA would set STATISTICS FRC SERVICE UNIFORM SUMMARY OF SURFACE OBSERVATIONS, PART D FAA MINIMA S WORLD CONCLUDING -P-U.S.A)' FOB CONTINENTAL OCCURRENCE PER CENT OF YEAR 1 £L KSL ?OQ 300 .4C C E I L I N G (FT.) VISIBILITYCMILES) Fig I. Incidence of various weather minima Fig 2. Cost of providing automatics for landing