Human-environment interaction in a small intramontane valley

advertisement

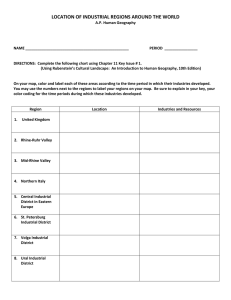

Human-environment interaction in a small intramontane valley Research from the Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project at Bereket (SW Turkey) Eva Kaptijn & Johan Bakker (eva.kaptijn@arts.kuleuven.be & g_v_r@gmx.net) Introduction The Bereket Valley, located in the territory of ancient Sagalassos (southwest Turkey), has been studied intensively by archaeologists, palynologists, and geomorphologists. This makes it one of the best investigated areas in the region and the multidisciplinary data provide an important added value. The Bereket valley is a high-altitude, intramontane valley. The presence of springs in combination with the poor draining capacity of the soils has resulted in the development of a marsh allowing palynological sampling. The territory of Sagalassos in the Roman Imperial period (solid line) and Hellenistic period (dotted line), with the Bereket Valley located in the southwest. Overview of the Bereket Valley and the surveyed area, with the ancient settlement (x), the modern village of Bereket (B) and pollen cores (stars). Archaeological research Distribution of RSW and SRSW sherds discovered in the survey Early Roman Imperial Late Roman/ Early Byzantine RSW 2 57 SRSW 79 22 Total 81 79 In 2008, the developments in past human activities were investigated by an intensive archaeological survey (Vanhaverbeke et al. 2011). The Bereket valley was almost completely surveyed, making the artefact collection a representative regional sample of past human activity. Study of the collected pottery and its distribution showed that a settlement existed in the southwestern part of the valley. This site was founded in the Hellenistic period and continued into the Middle Byzantine period, while the first centuries, i.e. the Hellenistic (333 – 25 BC), Early Roman Imperial (25 BC – AD 300) and Late Roman/ Early Byzantine (AD 300 – 650) periods are of special interest here. Beside the pottery, several remains of Early Roman monumental architecture have been found suggesting the presence in the valley of an elite population that could afford such expenditure. The pottery collection shows little differentiation between the Hellenistic, Early Roman Imperial and the Late Roman/ Early Byzantine periods; the number of collected sherds is similar, the functional division of the pottery is comparable and based on the archaeological evidence alone the same interpretation would be attachted to the artefact distribution in all periods, i.e. a village settlement located in a fertile, rural environment with, to all likelihood, a subsistence economy based on agriculture and a social organisation that included an elite population. However, a detailed investigation of the fine wares, more specifically the red slipped tablewares used for serving, revealed that during Early Roman Imperial period the red slipped tablewares originated as good as solely from the production centre located in the so-called potters’ quarter at Sagalassos (see table; RSW denotes the red slip wares from production centres other than Sagalassos, while SRSW stands for Sagalassos Red Slip Ware). Somewhere during the fourth century AD this changes and at least two, as yet unknown, production centres take the front, while the Sagalassos Red Slip Ware diminishes in importance to less than a third of the total amount of red slip wares. However, no changes occur in the number of red slip tableware sherds, or other types of pottery, that were collected. The change in proportion between SRSW and RSW might be indicative of changes at Sagalassos. The first half of the fourth century AD is evidenced to have the lowest output of SRSW during the existence of the production centre (Poblome et al. 2013). A similar dip occurs in the building activity at Sagalassos. Concluding, apart from the difference in production centre where the red slip tablewares were produced, no significant changes between the Early Roman Imperial and the Late Roman/ Early Byzantine periods are visible in the archaeological evidence identified in the Bereket Valley. Palynological research Discussion & Conclusions The Bereket Valley is palynologically amongst the most intensively investigated areas in the territory of Sagalassos. Within the Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project, two palynological studies have been carried out in this valley (Kaniewski et al. 2007; 2008; Bakker et al. 2013). The pollen data shows that the so-called Beyşehir Occupation Phase (BO-phase), a period characterized by an increase in the amount and variety of indicators for horticulture and attested in large tracts of Turkey and Greece, started in this valley around 280 BC (Kaniewski et al. 2007; 2008). In general, the start of the BO-Phase is placed around 1000 BC and linked to a climatic amelioration which apparently occurred throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Primary anthropogenic indicators in the valley consist of Cerealia, chestnut (Castanea sativa), manna-ash (Fraxinus ornus-tp), walnut (Juglans regia) and grape (Vitis vinifera/sylvestris), olive (Olea europaea), pistachio (Pistacia atlantica-tp), and hazel (Corylus). The fact that olive was present in these pollen cores is remarkable as at present the climate in this high-altitude valley is too cold for the culitvation of olive (Vermoere et al. 2003: 232). The local production of olive has also been suggested by the discovery of a counterweight of an olive or wine press in this valley. Bakker et al. (2013) report how recent pollendata points towards a distinct decrease in arboriculture during the second half of the 3rd century AD, corresponding with a short decrease in cereal cultivation. This is markedly earlier than the estimates generally given for the end of the BO-phase in the wider region, where the BO-phase continues until at least the mid sixth century AD (Bakker 2012).The shift at Bereket seems not to have been guided by a climatological need. The whole of the Roman Imperial period fell in what is known as the ‘Roman Warm Period’ (Bakker 2012: 84). This period contains wetter and drier episodes and the period from ca. AD 300 to 640 is generally considered to have been very wet. With regard to the cultivation of fruit trees and perennial crops, warmer and wetter conditions should be regarded as an amelioration of the climate. While encroachment of the marsh onto agricultural lands, due to a shift towards wetter climatic conditions, may be an explanation for a disappearance of local cultivated species such as cereals, it would not explain a decrease in cultivated trees, specifically olive trees, whose pollen may be transported over longer distances. Furthermore, olive continues to appear in pollen records from the nearby Gravgaz marsh after the disappearance of this tree from the pollen record of the Bereket basin (Bakker, 2012). The pollen data indicate that after the disappearance of intensive crop cultivation, open steppe and Juniper/Evergreen oak maquis became much more important (Bakker 2012). These vegetation types are often interpreted as being a result of heavy overgrazing by sheep and goats (Vermoere 2004). Given the unchanged presence of human habitation it is suggested that around ca. AD 300-350 a shift occurred away from agriculture and towards pastoralism. The combination of intensive archaeological survey and palynological research has revealed information on the subsistence and regional interaction of the people in the Bereket Valley that could not have been attained otherwise. During the Hellenistic and Early Roman imperial periods the Bereket Valley followed a trend of growing population pressure and intensification of agricultural activity, i.e. crop cultivation and arboriculture, visible throughout the territory. In this period, the city of Sagalassos assumed the role of regional political, administrative and economic centre, whose grip, even on peripheral areas, is attested in the presence of SRSW throughout the territory including the Bereket Valley. Somewhere in the first-half of the fourth century the intensification of crop cultivation halted and subsistence shifted from horticulture to pastoralism. Environmentally, there are no reasons to stop horticulture in a period when climatic conditions were becoming more ideal for this kind of cultivation. There are, furthermore, no indications to assume a depletion of the soil nor are there indications in the archaeological record for a crisis that forced people to change their mode of subsistence. The shift from horticulture to pastoralism is therefore more likely a change for positive reasons and might suggest a form of economic specialisation. Around the same time or slightly later, the production centre that provided the Bereket Valley with red slipped table wares shifted from Sagalassos as the only supplier to one or more as yet unknown centres. The lower availability of SRSW vessels, especially during the first half of the fourth century AD, might have prompted the inhabitants of the Bereket Valley to turn to other table ware suppliers to supplement the SRSW vessels. However, when the production at Sagalassos increased again, this did not lead to a renewed dominance of SRSW in the Bereket Valley. The relationship between the regional centre of Sagalassos and the peripheral Bereket valley had changed around the same time as when the mode of subsistence in the Bereket valley changed. Further study is needed to understand the reasons for these changes and the relationship between them. However, our preliminary results show the importance of a careful investigation of human environment interactions through multidisciplinary Summarized pollen percentage diagram, showing the relative abundance of a number of vegetation types, distinguished through multivarious numerical analyses (Bakker 2012; Bakker et al 2013). Olive cultivation ends during the second half of the 3rd century AD, while arboriculture on the whole (Fraxinus, Castanea) diminishes. Subsequently signs of arboriculture and agriculture gave way to open, herbaceous steppe vegetation (Artemisia, Chenopodiaceae, Ericaceae), followed by grass-dominated vegetation indicative of increased moisture availability at the sample site. research. Architectural remains discovered in the area suggesting elite presence This poster is based on research published in the article: View over the Bereket valley from the NE Sagalassos red slip ware Surveyors in action Kaptijn, E., J. Poblome, H. Vanhaverbeke, J. Bakker and M. Waelkens 2013: Societal changes in the Bereket valley in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods. Results from the Sagalassos Territorial Archaeological Survey 2008 (SW Turkey). Anatolian Studies 63, p.75-95. Bakker, J. 2012: Late Holocene vegetation dynamics in a mountainous environment in the Territory of Sagalassos, Southwest Turkey (Late Roman till present). Unpublished dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven Bakker, J., Paulissen, E., Kaniewski, D., Poblome, J., De Laet, V., Verstraeten, G., Waelkens, M. 2013: ‘Climate, people, fire and vegetation: new insights into vegetation dynamics in the eastern Mediterranean since the first century AD’ Climate of the Past 9: 57–87 Kaniewski, D., Paulissen, E., De Laet, V., Dossche K., Waelkens, M. 2007: ‘A high-resolution Late Holocene landscape ecological history inferred from an intramontane basin in the Western Taurus Mountains, Turkey’ Quaternary Science Reviews 26/17-18: 2201-18 Kaniewski, D., Paulissen, E., De Laet, V., Waelkens, M. 2008: ‘Late Holocene fire impact and post-fire regeneration from the Bereket basin, Taurus Mountains, southwest Turkey’ Quaternary Research 70-2: 228-39 Poblome, J., Willet, R., Firat, N., Martens, F., Bes, P. 2013: ‘Tinkering with urban survey data. How many Sagalassos-es do we have?’ in P. Johnson, M. Millett (eds), Archaeological Survey and the City, Oxford: 146-174 Vanhaverbeke, H., Waelkens, M., Jacobs, I., Lefere, M., Kaptijn, E., Poblome, J. 2011: ‘The 2008 and 2009 survey season in the territory of Sagalassos’ in A. N. Toy, C. Keskin (eds), Araştırma Sonuçları Toplantısı 28, Istanbul, 24 - 28 May 2010. Ankara: 139–53 Vermoere, M. 2004: Holocene vegetation history in the territory of Sagalassos (southwest Turkey). A palynological approach (Studies in Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology VI). Turnhout Vermoere, M., Vanhecke, L., Waelkens, M., Smets, E. 2003: ‘Modern and ancient olive stands near Sagalassos (south-west Turkey) and reconstruction of the ancient agricultural landscape in two valleys’ Global Ecology & Biogeography 12-3: 217-35