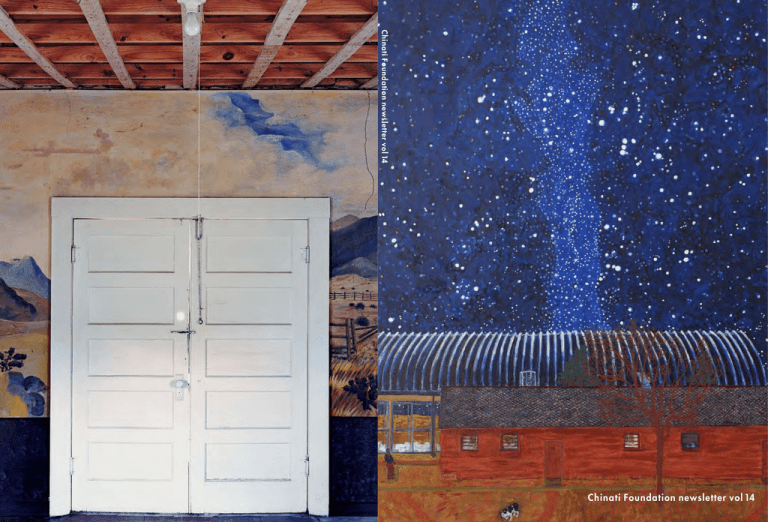

Chinati Foundation newsletter vol14

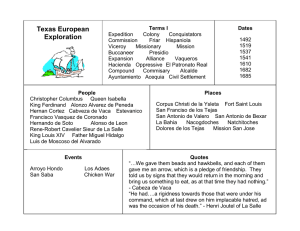

advertisement