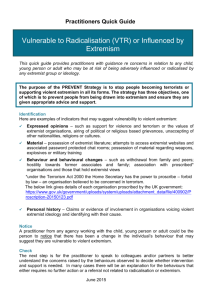

Counter-Extremism Strategy

advertisement