Selected Writings of MAHATMA GANDHI

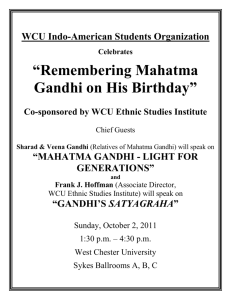

advertisement