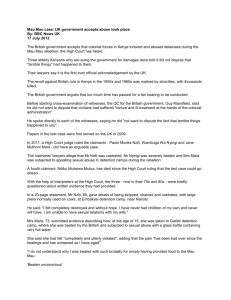

Mau Mau Remembered: How Narratives Transform

advertisement