Asian Migration and Linguistic Presence - part 1 and 2

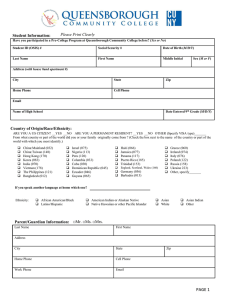

advertisement

Asian Migration and Linguistic Presence Parts I & II General Aims To examine the history of the migration of Asians to the Caribbean. What did the slaves and the planters do when slavery was abolished and how did this affect interaction/language? How did the arrival of substitute labour from (largely) Asia affect the linguistic picture of the Caribbean? To examine their mark on the linguistic situation on countries such as Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, and Suriname (to a lesser extent Cuba). Asian Migration -- Background British Colonies at the time Jamaica, Antigua, Dominica, St. Lucia, Barbados, St. Vincent, Grenada, Trinidad, Guyana Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana -- large territories Antigua, Dominica, St. Lucia, Barbados, St. Vincent, Grenada – small territories Asian Migration --Background Spanish - Cuba Dutch - Suriname French - Martinique, Guadeloupe Some territories had no immigration Haiti, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico & Barbados Asian Migration -- Background The Apprenticeship system ended in 1838. Mass exodus from the plantations on the larger islands (this will help to inform us why different colonies had different numbers of Asians). Labour shortage on larger plantations. Asian Migration - Background Marshall (in Beckles and Shepherd 1996) outlines three views of what Africans did upon emancipation. They were so horrified by slavery they left the plantations (where they could) and set up small villages in the interiors of territories (the Jamaican experience being the typical example) Asian Migration - Background In general, they stayed on plantations but many left eventually when wages/working conditions did not prove favorable (typically Barbados) Africans so acculturated to forced labour they vowed never to do arduous work of any type. Asian Migration - Background In Cuba abolition did not trigger a flight of labour. Many slaves became waged labourers, often in similar conditions to the life under slavery –in barracks, genders typically separated but a growing reconstitution of family life around the provision grounds. Others joined “caudrillas” or work gangs who hired themselves out to plantations and who moved depending on the terms of employment. Asian Migration - Background Situation seemed to be similar for the French colonies. Eric Williams reports the following: 1846 34,530 43,500 45,000 51,522 (h.c) (wkrs) (h.c.) (wkrs) 1856 32,000 (h.c.) Martinique 43,794 (wkrs) 32,000 (h.c.) Guadeloupe 51,659 (wkrs) Asian Migration --Background In Jamaica and Guyana substantial numbers of ex-slaves remained as waged workers. Hall (1996) Golden Grove Estate 1838 500 workers 1842 400 workers Asian Migration -- Background Labour began to leave the plantations (where they could) when planters began to charge rent for provision grounds and housing and when wages became uncompetitive (this is in a context of falling sugar prices and general economic problems). Asian Migration --background In the colonies of Barbados, Antigua and St. Kitts – so called high density colonies– where arable land was scarce because of the geography and the scope of the estates, labour was plentiful. Asian Migration - Background The West Indian planters pressed for liberal immigration policies to solve their labour problems. A number of immigration schemes were tried. West African Phased out in 1865/1870 for grater reliance on Indian immigrants European German, (poor English and Scots, French, Asian Migration --Background Portuguese North from Madeira America Asian Migrants – Why were they brought to the Caribbean? All other schemes were unproductive. They came chiefly to solve labour problems i.e. to satisfy the labour shortage on the plantations. Planters required cheap consistent labour. “The indenture system was a purely economic undertaking, and no attention was paid to the possible implications of introducing one more ethnic component into the West Indies” (Black et al 1976:53) Asian Migrants—Who came from where? Two main Asian groups came to the Caribbean. Chinese Indians Asians, by far, dominated numerically. Map of Asia Asian Migration – Who came from Where? As early as 1806 efforts were made to import people from Hong Kong (China) , Singapore (Malaysia) and Calcutta (India) to settle as peasant farmers and to replace Negro domestic slaves in Trinidad. Asian Migration -- China Chinese were recruited mainly from Canton. They were generally Hakka/Cantonese After the mid 19th Century a large number came to the West Indies as contract labourers, but they tended to drift into towns, where they acted as brokers and distributors of food and small shopkeepers. Asian Migration -- China Between 1853 and 1879, British Guiana imported more than 14,000 Chinese workers, with a few going to some of the other colonies The Chinese languages brought to the Caribbean were Cantonese Mandarin?? (to the extent that standard speakers migrated to the West Indies) Asian Migration -- India In July 1844 the British government gave permission for West Indian colonies to import labour from India chiefly at their own expense (minor imperial assistance). Calcutta and Madras were designated as ports of embarkation in India. Asian Migration -- India Recruiting agents were paid bounties (per head). Indians were recruited from the cities and the depressed areas of the Granges Valley. In 1846 the first shipload of 226 Indians arrived in Trinidad from Calcutta. Asian Migration – India & China According to the rules, they(Indians) were to be Allotted to estates in parties of 20-25 or 50 under a headman or sidar. Given medical care, housing, provision grounds, monthly food rations, yearly allotments of clothing and free return passage after their contracts expired. Asian Migration –India & China Contracts were for five years; nine hours per day; six days per week Immigrants were bound to reside on the plantations which indentured them. Land grants (among other more dishonorable tactics) were used to induce immigrants to remain on plantations after their contracts ended Asian Migration -- India The Indian indentureship system was abolished in1917. Between 1838 and 1917, nearly half a million East Indians (from British India) came to work on the British West Indian sugar plantations, the majority going to the new sugar producers with fertile lands. Trinidad imported 145,000; Jamaica, 21,500; Grenada, 2,570; St. Vincent, 1,820; and St. Lucia, 1,550. Asian Migration cont’d Chinese were the main immigrants to Cuba. By 1877 Cuba had 54,000 Chinese. (Indentureship in Cuba abolished in 1921) Jamaica 37, 000 Indians up to 1921, 4, 500 Chinese up to 1946) Guyana 1838 – 1900 165,000 Indians, 13,000 Chinese, 12,000 Portuguese Asian Migration cont’d Guadeloupe Indians 42,500, Africans 6,500, Chinese 500, Madeira, 413, Japanese 500 Suriname 22,000 Javanese (1890- 1939). By 1971 the Surinamese Javanese community numbered 60,000, comprising 16% of the population of the colony. 34,000 Indians (1873-1916) Asian Migration cont’d Trinidad (1845-1916) 145,000 Indians, & 4,000 Chinese Indian languages which were brought to the Caribbean Bhojpuri speakers were not the first Indian indentured labourers to be brought to the Caribbean. For the first 15 years of organized emigration most recruits came from Chhota Nagpur, the Calcutta hinerland and Calcutta itself. These people were native speakers of Bengali, Oraon, Mundari and Santali and Tamil (recruits brought from the Port in Madras) Indian languages cont’d Of these first language only Tamil took root in tiny pockets for almost a century in Trinidad. By 1860 recruiting concentrated on Bihar where regional dialects of Bhojpuri, Maithili and Maghi were spoken and later on Uttar Pradash where Western Bhojpuri and the Eastern Hindi dialects, mainly Avadhi were found. Indian languages cont’d Some labourers also came from further west and spoke dialects of Western Hindi and Braj. Note---Though all labourers were Hindi speakers they actually spoke geographical varieties which were very different from each other and since labourers were uneducated they did not know Standard Hindi or Urdu. Linguistic impact of Asian Migration Introduction of new languages into the language mosaic which already existed in the Caribbean. LINGUISTIC IMPACT OF INDIAN MIGRATION For Indians – there were new patterns of language contact, both internal and external, resulting in many linguistic changes. Linguistic impact of Indian Migration cont’d There was increased interaction among speakers of the different geographical dialects. In the new environment (Caribbean) they needed linguistic unity. This led to dialect levelling and dialect mixing. Linguistic impact of Indian Migration cont’d There were external contacts with Indigenous, European and Creole languages which caused large scale borrowing and some structural changes. Vertovec (1996) provides an 1855 comment “when these people meet in Trinidad it strikes one as somewhat strange that they may have to point to water and rice and ask each other what they call it in their language.” Linguistic impact of Indian migration cont’d For Indians – the development of a new varieties of Hindi (Overseas Hindi) distinct from any form of Hindi in India. Each developed under similar social and historical conditions yet have been maintained in varying degrees. Overseas Hindi Among the places where what is referred to as Overseas Hindi developed were Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname. Guyanese Bhojpuri Indians emigrated form 1838 – 1916 (78 years). Today Guyanese Bhojpuri is used only in a very limited way by members of the oldest generations in rural areas. Guyanese Bhojpuri cont’d Rural men and women over 60 ---bilingual in GB and Creole/English Between 35 and 59 years ---passive bilinguals Under 35 –monolingual in Creole/English GB has very limited use in the home but is used in some folksongs. Trinidad Bhojpuri Indians emigrated between 1845 and 1916. Spoken by old, usually rural Indians. It has been displaced by Trinidad English Creole. NB—Standard Hindi is an important ethnic language in Trinidad today. Sarnami Hindi/Sarnami Hindustani/Sarnami Between 1873 and 1916 some 34,000 Indian labourers left North India for Suriname two thirds of which settled there (Damssteegt 2002:249). In 1980s there were approximately 130,000 speakers (Damsteegt 2002:251). Sarnami Hindi/Sarnami Hindustani/Sarnami cont’d Although there is widespread bilingualism there has not been a significant shit to Sranan (the local Creole) or Dutch (the official language). Sarnami Hindi is the only variety of Overseas Hindi which has been recognized as a language in its own rights but is not extensively used outside informal contexts. Social factors and the loss of Asian vernaculars in most C’bbean Terr. All instances of language death are the result of language shift. Investigating the processes leading to language death therefore means studying language shift situations. Social factors and language loss…cont’d With regard to the phenomenon of language death two levels are involved. The environment –political, historical, economic and linguistic realities. The speech community –patters of language use and attitudes Social factors and language loss… cont’d. Concerning the first level – the environment– factors such as status, demography, institutional support (education and employment), time and space, urbanization, occupation, contact with other groups, pragmatics, access to information, entertainment and the arts, cultural (dis) similarity are relevant. These influence the second level –speech community (patters of language use and attitude) Social factors and language loss…cont’d. In terms of causal relations then, changes within the speech community very often have to be understood as reactions towards environmental changes. Minority languages are the ones threatened by extinction in language shift situations. Social factors and language loss…cont’d The minority language has to be valued highly by the members of a speech community in order for it to survive a generally hostile environment. Patterns of language choice reflect language attitudes. Social factors and language loss…cont’d In cases of language shift one has to investigate underlying changes in attitude towards the languages involved, that is the abandoned language and the target language. Additionally investigations have to be made into Social factors and language loss… cont’d Internal pressure on minority languages such as limited communication yield caused by restricted distribution of the language. External pressures on minority languages such as stigmatization, exclusion from education and political participation and economic deprivation. Social factors and language loss…cont’d The actual process of abandoning a language may be observed in a decrease in Number of speakers Functional domains Competence Social factors affecting language maintenance and shift Asian vernaculars in general have had no practical value -- they have never been (widely) used in broadcasting, newspapers, information distribution or entertainment in the form of films, education, employment etc. European varieties are used for these purposes. Social factors cont’d Pragmatic aspects Concerns how widely the language is used and the benefits gained by its use. In Guyana and Trinidad OH is dying because the oldest generation of speakers did not regard the language as having practical value, so it was not transmitted. Languages have practical value in areas such as education, employment, wider communication, access to information, entertainment etc. Situation is similar for the Chinese. Social factors cont’d Urbanization and Occupation Language shift usually occurs more readily in urban areas because of the increased contact. People usually migrate to urban areas in search of greater employment opportunities. Language shift from Overseas Hindi in Trinidad and Guyana is more extensive in urban areas. (In general, urbanization does not necessarily lead to widespread language shift, but when the shift begins, it may occur more rapidly among the urban population. Social factors cont’d Urbanization and Occupation cont’d Maintenance of occupation promotes language maintenance. Mohan and Zabor (1986:315) report a close relationship between having been a labourer on the sugar estates and high competence in Trinidad Bhojpuri. Two factors which have conditioned the near loss Trinidad and Guyanese Bhojpuri therefore are the shift in occupation and urbanization. Social factors cont’d Demography Chinese were not a numerically dominant group (except in Cuba). Numerically nondominant groups are usually under pressure to conform. Social factors affecting language maintenance and shift Size of the group is sometimes an ambivalent factor. The expectation is that the large size of the Indian communities would have encouraged language maintenance. In terms of actual numbers the country with the smallest Indian population, Suriname has one of the thriving varieties of overseas Hindi. Social factors cont’d Time and space can also be an ambivalent factor. Longer history of migration is usually a factor in language maintenance but Suriname which had the shortest years of Indian migration is the only speech community with OH thriving. Trinidad (71years), Guyana (78 years) Suriname (43years). Social factors cont’d Contact with other groups. Related to urbanization and occupation—less contact, the greater the chance of maintenance. Indians working and living in sugar estates in the rural areas are usually isolated from other groups (Guyana). Social factors cont’d Education and Employment European languages served as official in Caribbean territories before and after independence. In Trinidad and Guyana, OH has no official place in education and employment. Gambhir (1981:3) the major reason for the shift from OH has been the importance of learning English for success in education, for economic gain and for political power. Social factors cont’d Wider communication No Asian vernaculars have been useful for intergroup communication. The advantage of having another language for wider communication within a country may be an important factor in language shift. (In Suriname however, Sranan is the lingua franca but there has been no shift from Sarnami -ethnicity issues)