i o STARKER LECTURES LIs,

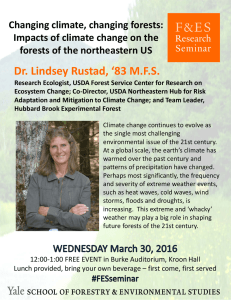

advertisement