Inhibition to excitation ratio regulates visual system responses and behavior... vivo Wanhua Shen Caroline R. McKeown

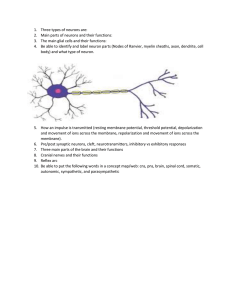

advertisement