GROW YOUNGSTOWN A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

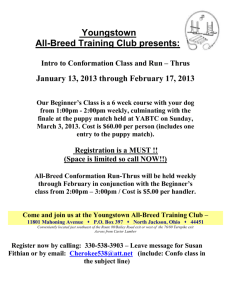

advertisement