Document 10897509

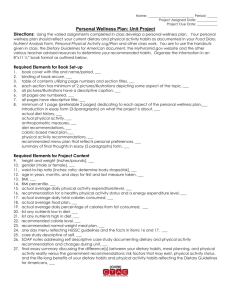

advertisement