Theories of Language and Gender

advertisement

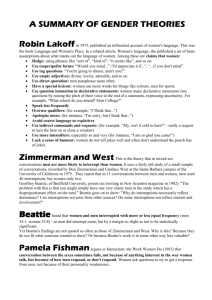

Theories of Language and Gender How do men and women speak differently? AIMS To revise some of the theories about men and women’s use of language Broadly speaking… • Language and gender theories, over time, have moved through several stages: • The deficit model • The dominance theory • The difference theory The Deficit Model • This is the idea that there may be something intrinsically wrong with the language of a disadvantaged group. • Theories which fall into the deficit model analyse language by seeing men’s language as the norm and women’s language as deviating from that norm in various ways. • Otto Jesperson wrote in these terms… Otto Jesperson (1922) • One of the first linguists to write about male and female language. He had a chapter in his book entitled ‘The Woman’ • He believed that: – women had limited vocabularies – women are delicate and easily offended, so prefer to avoid ‘coarse and gross expressions’ and use more ‘veiled and indirect expressions.’ – Men invent new terms, while women are naturally conservative. – “there is a danger of the language becoming languid and insipid if we…content ourselves with women’s expression” while male language adds “vigour and vividness” to the English language! The Dominance Theory • Men dominate and control both interactions with women and the language system itself. • Women use language in a way which reflects their subordinate position in society, and men in a way which reflects their power. • Differences in men and women's speech is due to men's dominance and women's subordination. • Therefore the language we use is more about power and status than gender Dominance Approach • 1. Lakoff (1975) claimed that the differential use of language needed to be explained in large part on the basis of women's subordinate social status and the resulting social insecurity. • 2. Dale Spender (1980) "It is the men, not women, who control knowledge, and I believe that this is an understanding we should never lose sight of”(from "Man Made Language") • 3. Zimmerman and West (1983) 99% of interruptions are made my males. They concluded that men's dominance in conversation via interruption mirrors their dominance in contemporary western culture. Interruption is "a device for exercising power and control in conversation" (West & Zimmerman, 1983, p. 103). Men typically enjoy greater status and power than women in most societies, and they are more likely than women to assume they are entitled to take over the conversation. Robin Lakoff (1975) Lakoff published a series of basic assumptions about what she believed to be typical of women’s language: • • • • • Hedge: using phrases like “sort of”, “kind of”, “it seems like”, etc Use (super)polite forms: “Would you mind...”,“I'd appreciate it if...”, “...if you don't mind”. Use tag questions: “You're going to dinner, aren't you?” Speak in italics: intonational emphasis equal to underlining words - so, very, quite. Use empty adjectives: divine, lovely, adorable, etc Robin Lakoff (1975) • • • • • Use hypercorrect grammar and pronunciation: English prestige grammar and clear enunciation. Use direct quotation: men paraphrase more often. Have a special lexicon: women use more words for things like colours, men for sports. Use question intonation in declarative statements: women make declarative statements into questions by raising the pitch of their voice at the end of a statement, expressing uncertainty. For example, “What school do you attend? Eton College?” Avoid coarse language or expletives Lakoff contd… Lakoff’s theories still have much support, although some are more difficult to assess, such as women lack a sense of humour because they do not tell jokes well and often don't understand the punch line of jokes. • Another central idea of Lakoff’s was that women were socialised into sounding like ‘ladies’, which then kept them in their place because being ladylike is a bar to being powerful in our culture. If women talked like ‘ladies’ they were seen as powerless and trivial, but if they talked like men, they were considered unfeminine. Zimmerman and West (1975) • Men interrupt more often than women • Men seek to dominate talk • In 1975, Don Zimmerman and Candace West analysed conversations in a college community, focusing on interruptions. • An important point about this very famous research is that it is a fairly old study of a small sample of conversations. All subjects were white, middle class and under 35 years of age. Peter Trudgill (1970s) • Women use high prestige pronunciation as they aim for overt prestige (social class) • Men use low prestige pronunciation seeking covert prestige by appearing tough or down to earth • There is a tendency for men to use more vernacular forms (common language / dialect of a specific area) • An example would be verbs ending in -ing, where Trudgill wanted to see whether the speaker dropped the final g and pronounced this as ‘-in'. Dale Spender (1980) • Language itself sustains male power • Men seek to dominate women through talk • Men tend to speak in non-standard forms with covert prestige as a means of social bonding (carries on from Trudgill’s research) Dale Spender agrees with and develops Zimmerman and West’s dominance theory. Her radical view is that it is difficult to challenge male-dominated society because our very language reinforces male power. Dominance approach LAWYER: And you saw, you observed what? WITNESS: Well, after I heard- I can’t really, I can’t definitely state whether the brakes or the lights came first, but I rotated my head slightly to the right, and looked directly behind Mr. Z, and I saw reflections of lights, and uh, very, very, very instantaneously after that, I heard a very, very loud explosion – from my standpoint of view it would have been an implosion because everything was forced outwards, like this, like a grenade thrown into a room. And, uh, it was, it was terrifically loud. • TASK – Which is male, which is female – why? TASK From Mullaray (2003). Steve – manager running a meeting. He is trying to get his subordinates to run their own induction day.) Steve : Do you feel that (-) we need to do perhaps something like (-) the sales department did? Mike: Set a date to sort it out Steve : Cos as Sue’s quite rightly pointed out, all it’s all been done for us and the things etc. why don’t we just take advantage of that? (.) Sue’s offered her support with perhaps John? (-) Err you know perhaps to run that (-) why don’t we just set a date now? Matt : Yeah Steve: And say right okay let’s do it Sue : Just get everybody in Matt : Yeah TASK • What aspects of Steve’s language are stereotypically female? • Why is he using these features? Difference Approach • Difference – sees men and women belonging to different sub-cultures, who because they are socialised differently from childhood, have different ways of communicating with each other. e.g. women are more supportive in conversation, because they’re brought up to be facilitators (Fishman, 1983) Language and Gender: Language in use Difference approach: Gimme the ball! Now!! Let’s go downstairs and get some pizza..? Deborah Tannen (1992): Difference Approach: six contrasts • • • • • • Status vs. support Independence vs. intimacy Advice vs. understanding Information vs. feelings Orders vs. proposals Conflict vs. compromise In each case, the male characteristic (that is, the one that is judged to be more typically male) comes first. Status versus support • Men grow up in a world in which conversation is competitive - they seek to achieve the upper hand or to prevent others from dominating them. • For women, talking is often a way to gain confirmation and support for their ideas. • Men see the world as a place where people try to gain status and keep it. • Women see the world as “a network of connections seeking support and consensus”. Independence versus intimacy • Women often think in terms of closeness and support, and struggle to preserve intimacy. • Men, concerned with status, tend to focus more on independence. These traits can lead women and men to starkly different views of the same situation. • Professor Tannen gives the example of a woman who would check with her husband before inviting a guest to stay - because she likes telling friends that she has to check with him. • The man, meanwhile, invites a friend without asking his wife first, because to tell the friend he must check amounts to a loss of status. • (Often, of course, the relationship is such that an annoyed wife will rebuke him later). Advice versus understanding • Deborah Tannen claims that, to many men a complaint is a challenge to find a solution: • “When my mother tells my father she doesn't feel well, he invariably offers to take her to the doctor. Invariably, she is disappointed with his reaction. Like many men, he is focused on what he can do, whereas she wants sympathy.” Information versus feelings • A young man makes a brief phone call. His mother overhears it as a series of grunts. Later she asks him about it - it emerges that he has arranged to go to a specific place, where he will play football with various people and he has to take the ball. • Men focus on conveying information as quickly as possible • A young woman makes a phone call - it lasts half an hour or more. The mother asks about it - it emerges that she has been talking “you know” “about stuff”. The conversation has been mostly groomingtalk and comment on feelings. • Women focus on sharing emotions and elaborating on details • Historically, men's concerns were seen as more important than those of women, but today this situation may be reversed so that the giving of information and brevity of speech are considered of less value than sharing of emotions and elaboration. Orders versus proposals • Women often suggest that people do things in indirect ways - “let's”, “why don't we?” or “wouldn't it be good, if we...?” • Men may use, and prefer to hear, a direct imperative – ‘We’ll go to the Red Lion first then get last orders in the Railway’ Conflict versus compromise • “In trying to prevent fights,” writes Professor Tannen “some women refuse to oppose the will of others openly. But sometimes it's far more effective for a woman to assert herself, even at the risk of conflict. ” • This situation is easily observed in work-situations where a management decision seems unattractive - men will often resist it vocally, while women may appear to agree, but go off and complain subsequently. • Of course, this is a broad generalization - and for every one of Deborah Tannen's oppositions, we will know of men and women who are exceptions to the norm. Jennifer Coates (1998) • Sees women’s simultaneous talk as supportive and cooperative • Women use tag questions to interact sensitively in conversations Coates sees many features of women’s talk, such as tag questions, as a means of communicating sensitively and appropriately, respecting the face needs of the listener. Language and Gender: Language in use Critiquing the difference and dominance approaches • Are all men and women ultimately the same? They’re presented by the research as homogenous categories – is this really true? • Do men always have power in society? Don’t some women have power too? • Do boys and girls always socialise in single-sex groups only? What happens when they interact? • The research seems to find evidence for popular stereotypes of men and women – is there anything wrong with this? What other stereotypes might be proved – or disproved?