Art Institute Paper

advertisement

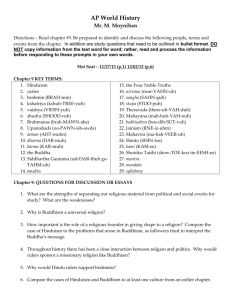

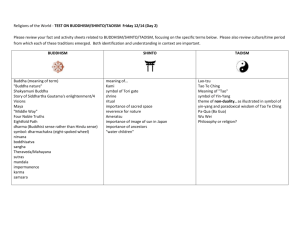

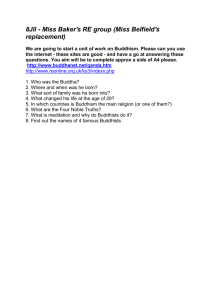

Jane Meyer Ancient World Finch 12 November 2009 Art Institute of Chicago I. India Figure 5 Figure 3 Figure 4 India’s central cultural glue centers around its religion and the society religion imposes or upholds. In Hinduism, which developed after the Aryan invasion around 1500 B.C.E, Brahman, or the “Essence of the universe,” manifests itself in three different gods: Brahma, the creator; Vishnu, the preserver; and Shiva (Figure 1), the destroyer (Benton 262). Much of this early art depicted these gods along with Vishnu’s early forms called avatars (262). Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi’s son, Ganesha (Figure 2), is fond of sweets and wears a snake tied around his middle; his rat vehicle tripped on a snake and his sweets fell out of his stomach (262). Buddhism rose in reaction to the increasing corruption of the Brahman class. Buddha, who lived between 563 and 483 B.C.E, discovered that human greed and connection to impermanent, material things cause suffering. Although Buddha upheld reincarnation, he did not support the caste system. Under Ashoka’s rule (during the Mauryan period- r. 269-232 B.C.E), India underwent mass conversions to Buddhism. Art now took the form of Buddha, seated, deep in mediation. However, after the fall of Ashoka and the Mauyran Empire, Hinduism experienced a renaissance. In the Gupta period (4th- 6th century C.E), the monasteries tried to fight this come back by developing thirty-two physical characteristics of Buddha, making his form increasingly iconic. The seated Buddha in Figure 3 has three of these laksanas. One, the ushnishna, or cranial protuberance; two, the urna or round mark on the center of the forehead to “symbolize the power to illuminate the world; three, the elongated ears (269). Although these measures helped Buddhism spread and take hold in other parts of the East and North, lack of connection between the monasteries and the everyday people and royal patronage contributed to Hinduism’s dominance. Yet Buddhism still influenced ancient art greatly. Figure shows a Buddha in Pakistan. Notice the Greek-like robes, left over influence from Alexander the Great’s invasion, and the mustache which marks the piece as Pakistani. Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 1 II. Greece Ancient Greeks developed unprecedented styles such as the blackfigure style of ceramics and idealism of sculpture. During the Orientalizing Period (700-600 B.C.E), Figure 1 the Greek city states established trade Figure 1 links and made contact with Egyptain and Persian civilizations (Benton 66). During this period, arts produced oinochoes (wine jugs) and olps (66). In the Archaic period, the ancient Greeks experimented with black figure styles, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. In this style, “black glaze [covers] a natural orange clay background…details are created by scraping through the black glaze to reveal the orange clay underneath (67). As the classical period commenced, the Greeks devoted a great deal of time and effort to sculpture and architecture. The Athenian city state under Perikles built edifices on the acropolis such as the Parthenon. In sculpture, such famous artists as Polykleitos and Praxiteles focused on ideal human forms. Figure 3 parallels the Spear-bearer (ca. 440 B.CE) and the written rules of Polykleitos which base measurements off of the size of the head (98). The subject of Figure 3 links the artwork of Athens to the war culture of Sparta. Although Sparta produced Figure 4 little art compared to Athens, their dedication to building a war society led to victory in the Peloponnesian War. Like Figure 4, the female form arose later in the classical and throughout the Hellenistic period. Although the woman in Figure 4 is not nude like Aphrodite of Knidos (ca. 350-200 B.C.E), the realistic depictions of the falling robe is similar to that in Praxiteles’ masterpiece. Figure 3 Figure 4 III. Egypt The Pyramids and tombs of the Ancient Egyptians remain one of the greatest wonders of the modern world. Developing slowly from around 5000 B.C.E, the Ancient Egyptian culture gained a political center around 3100 B.C.E when Narmer united upper and lower parts of the Nile. Although the pyramids of Gaza serve largely as a symbol of the entire culture today, the Egyptians also developed sophisticated language, architecture, and sculpture. The hieroglyphics has roots before 3000 B.C.E, and grace a great deal of the Egyptian artwork. As present in Figure 1 and 2, the hieroglyphs “not only [read] symbolically but phonetically as well” (Benton 19). The sculpture King Menkaure and Queen (ca. 2490-2472) as well as the Figure depicted in the tomb reliefs embody the “composite view of the human body” and allow the eye to fill in what is missing (26). The language and artistic tradition remain largely Figure 1 unchanged throughout the 3000 years of the Ancient Egypt civilization, all mediums united under the common theme of a stable religion. According to Benton, “much of the Egyptian life appears to have been oriented toward preparing for the hereafter” (21). In order to ensure the preservation of the ka, or fundamental essence of a person, the deceased body was embalmed and bound, and large pyramids constructed to allow the divine monarch entrance to the world of the gods. The Egyptians, during the Old Kingdom, built massive pyramids which have roots in the mastabas of the Mesopotamian culture. Composed of millions of sandstone and limestone blocks, the Pyramids of Gaza reflected the unification of all classes of people, not only slaves, in preparing for the afterlife. All Figures 1-4 have connections to the polytheistic religion. Figures 3 and 4 served as covers for the mummies inside the tombs of the New Kingdom (1552-1069 B.C.E). The ornate decorations and extensive use of gold attracted many grave robbers. Figures 1 and 2 are blocks of tomb walls. Figure 2 in particular reflect fundamental artistic elements. Like Ti Watching a Hippopotamus Hunt (ca. 2500-2400 B.C.E), the artist uses relative sizes to indicate social superiority and inferiority. The relief also depicts the human figure in a profile view in an impossible position. These values continued unchanged through to the New Kingdom (see Figure 2 Nobleman Hunting in the Marshes ca. 1400 B.C.E), only briefly interrupted by Akhenaten. Figure 3 IV. Rome Figure 1 Figure 2 Although the Romans conquered the Greeks, the Greek culture not only preserved by served as the foundation for Roman art, architecture, and religion. Indeed, the Romans often copied bronze Greek sculptures in marble. Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos shown on page 97 in Benton is actually a Roman copy, the Greek original having been destroyed. Figure 1 shows the bust of the Roman god of war, Mars. The Romans renamed the Greek gods (Ares→Mars). Figure 1 also embodies the Roman transition from the Greek idealism to realism. Although the sculpture Augustus of Primaporta (ca. 20 B.C.E) has more idealized features, they remain uniquely Augustus’’, indicating the Roman emphasis on individuality. In Figure 2, the Portrait Bust of a Woman (ca. 140-150 C.E), the drapery of the clothing parallels the clothing in Greek sculptures (such as the Three Seated goddesses on the east pediment at the Parthenon). Roman also developed sophisticated paintings at such cities as Pompeii. According to Benton, painting consisted of four different styles. The First Style, or “masonry style,” started around the 2nd century and is characterized by wall decorations that “imitated the appearance of colored marble slabs” (Benton 158). During the Second Style, or “illusionistic style” between 80 B.C.E and 20 B.C.E, architectural structures were colored and copied into paint (159). The Third Style, “ornamented” style, the emphasis shifted to capturing decorative detail (160). The freer, and sketch-like qualities of the Four style, which began around 62 C.E. was cut off by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E (160). Ironically, although the eruption destroyed the city, it preserved their painting styles. Figure 4, a portion of a mosaic floor, also represents the highly decorative and ornate style of the Romans. Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 1 V. China While religion and social structure might hold the Indian civilizations together, the Chinese social glue arises from Figure 2 a highly centralized and organized bureaucracy supported by philosophy. Comprised of many dynasties, the history of ancient China reflects an unprecedented level of cultural sophistication. During the Shang, Zhou, and Qin dynasties, artists experimented with bronzes and other metals as part of a Neolithic age in China (Figues 1, 2). During these periods the Chinese also started a tradition of ceramics with small handbuilt figures (Figures 3 and 4). The Zhou, conflicted with a weak political structure and the Qin, troubled by a rigid and demanding bureaucracy headed by the Legalists, gave Figure 4 way to the artistic Golden Age of the Han (202 B.C.E -220 C.E). The Han’s artwork was characterized by many clay figurines that would reside in the tombs of the nobility (Figures 5 and 6). The political turmoil after the fall of the Han contributed to the rise of Buddhism in China. Throughout the Sui and Tang dynasties, sculptures of Buddha were constructed along with many monasteries (Figure 12). Under Empress Wu of the Tang dynasty, Royal patronage reached a height. However, the Confucians resurged under Neo-confucian which combines Buddhism and Toaism into a single school of thought, declaring the importance of finding individual morality. By the late Tang period, under Emperor Wuzong, the distain for Buddhism translated into open persecution. Many monestaries and Buddha figures were destroyed, hence the lack of Buddhas at the Institute of Art. Yet the Tang and the Song had their own cultural achievements, largely fueled by the resurgence of Confucianism. The produced famous poets such as Li Bai and Du Fu and also produced pottery (Figure 10). However, it was during the Song period that reached its height; Song pottery is often characterized by various green glazes (Figure 7), reached its height. Neo-Confucianism paintings of landscapes (Figure 9) continued into the Ming period, highlighting vital elements of Taoism. Figure 3 Figure 5 Figure 1 Alhtough the Chinese had a national pottery market, until the Ming and later dynasties, the Chinese did not focus production on exportation. However, as contacts with the west increased, Chinese pottery became more decorative, hoping to attract the western eye. Figure 11 is such a piece, adorned with the eight immortals of Taoist mythology. Figure 10 Figure 7 Figure 9 Figure 11 Figure 12 Figure 1 VI. Japanese Although Japan’s geographic location largely isolated the island from the western influences, in the ancient time period, Japan participated in an elaborate cultural exchange with mainland China and Korea. Most significantly, Buddhism, traveling along the Silk Road from India, to China, and finally to Japan, fused with Shinto in creating a uniquely Japanese religion. Around the 5th and 6th century, a wave of immigrants bought a complex writing Figure 3 system, medicine, poetry, and Buddhism to Japan. Originating in India, Buddhism identified greed and humans relations to impermanent things as the originator or human suffering. Similar to the Indian iconic Figure 2 Buddha, Japan’s Shakayamuni and lesser deities (including the Bosatsu in Figure 1) is often depicted in a cross-legged position. Figure 1 and the Shaka Triad (Ashuka period) embody this international connection and the “awareness of the Chinese sculptural tradition from the pre-Tang period, including the focus Figure 1 of attention on the large head and hands” (323). Figure 4 Yet the Japanese often used wood, a scare resource, in their artwork rather than stone or clay (Figure 4). The other influential faith, Shinto, remains in active practice today as well. According to Benton, Shinto “developed from a kind of nature worship into a state religion of patriotic appreciation of Japanese land” (321). In other words, Shinto combines nature and ancestor worship with ritualistic actions. Kami, or gods, originate from Izanagi and his consort Izanami. Figure 2 shows the Shinto deity Hachiman whose cult embraced many different philosophies of life, including Buddhism. The flowing robes relate to the Roman and Greek clothing that was carried along trade routes and by Alexander the Great to India. This Buddhalike figure shows the incorporation of Shinto and Buddhist beliefs into architecture and art. Figure 3, a warrior who would protect a monastery, not only represents the rise of Buddhism in Japanese culture, but the importance of warriors. In the later Heian period, regional warriors, the samurai, gained more power over the actual rulers, and thus began the Kamakura period (11851333 C.E). During the period, Zen Buddhism, with its stress on self-discipline and inner strength, increased in popularity. Figure 2 VII. The Americas The Americas developed in geographic isolation of the eastern world containing the Roman Empire and the Chinese dynasties. Instead, these eclectic civilizations developed their own vibrant religions and art work (and in the Mayan and Aztec cultures, calendars and Figure 1 mathematics the rivaled the ancient Babylonians). One of the earlier civilizations was the ancient city of Teotihuacan which rose to power after 300 B.C.E. The height of Teotihuacan’s innovation comes in the form of tow large pyramids, the Pyramid of the sun and the Pyramid of the Moon which centered around the Avenue of death. Actually made up of many ziggurats, the Pyramids “suggest [the city’s role] as an astronomical and ritualistic center” (342). Figure 1, the mask of an incense burner portraying the god of fire (ca. 450 C.E), embodies this rich religious tradition and social hierarchy surrounding religion. Figure 2, a mural fragment carved around 600-750 C.E, represents the ritual of the renewal of the world. The Teotihuacan declined due to an ecological disaster from pillaging surrounding land for lime. The Mayan culture (250 B.C.E – 900 C.E) developed in the Yucatan peninsula. Their complex ritual and time-keeping system, based off of two calendars, one a 365 day calendar and the other a 260 day ritualistic calendar, matched Teohuacan’s precision. The extensive writing system not only recorded these astronomical observations but also documented the genealogies of rulers and the records of their victories. Figure 3 shows a profile of a Mayan ruler made in the late classic Mayan period (650-800 C.E.). The Maya civilizations centered around many cities, one of the most important being Tikal. As a great political center, Tikal contains six giant temples in six miles. In addition, the Mayan ruler held great religious significance, letting his own blood to give sustenance to the spiritual world. According to the Mayan legend of origin (the Popol Vuh), the gods created humans to amuse them, finally succeeding Figure 4 in their creation attempts on the third try. Made out of maize and water, this narrative reveals the importance of agriculture for sustaining the Mayan culture. The Wacan Chan, a great tree, connected the three worlds. Like the Olmecs and the Aztecs, the Mayans worshiped the Jaguar God. The ball game (carved into stone in Figure 4) has long captured the interest of historians. Although sometimes the players bet their worldly Figure 3 possessions, sometimes their lives were at stake; if they lost, they would be sacrificed. The Moche (200-700 C.E) arose out of the northern coast of Peru. Like the people of Teotihuacán, the Moche built large huacas or “pyramids made of sun-dried bricks” (Benton 349). Unfortunately, the Spanish dug into these pyramids and captured many gold pieces and melted them down, thus contributing to the rarity of such artwork at the Institute of Art. The Moche were skilled potters and sculptures, using molds and firing techniques with temperatures that reached up to 800 degrees Celsius. Like the Romans and regional civilizations in India, the Moche used a lost-wax technique. Around 800 C.E, the Moche fell, perhaps to an ecological disaster caused by an earthquake and the Nino. Calling their empire the Tawantinsuyu, the Mayans created a strong empire with an extensive infrastructure that rivaled that of Romans. Highways and runners allowed information to circulate quickly through the mountainous region. The Inca’s engineering is best shown through Machu Picchu, a religious refuge built in the Andes without the benefit of carts of wheels. Inca society, like that of India, consisted of highly stratified classes with the rulers on top and the peasants on the bottom (priests and the aristocracy in between). The Inca rulers owned all of the land in the empire. According to Benton, “their rule was absolute, and they retained their exalted position after death” (352). Similar to the rulers in Egypt, the rulers served as intermediaries between and the god and the people, and thus their death required great ritual (mummification in both cultures). The Inca fell to the Spanish whose war tactics, guns, and disease soon decimated local populations. Figure 5 groups and the importance of hunting. The Buffalo hunters in the Great Planes of North American retained their nomadic culture. Tribes moved about, following the great buffalo herds and using the stampeding technique for mass slaughtering. This tradition continued until the English and the American government killed the Buffalo in order to subdue the Native Americans into a position of dependence. Indeed, Benton notes that between 1830 and 1870, “the buffalo population in the West dropped from around 30 millions…to 8 million” (355). Figure 5, a painting on hide created in 1870, shows the warrior culture of these