Commentary_Ch_4_Crowley

advertisement

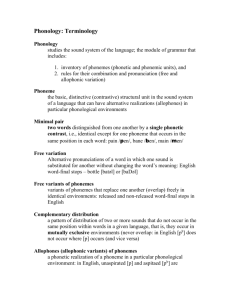

Commentary on Crowley Chapter Four PHONETIC AND PHONEMIC CHANGE This chapter discusses six topics. Phonetic change without phonemic change Phonetic change with phonemic change Phonemic loss Phonemic addition Rephonemicization shifts mergers splits This chapter discusses six topics. 1. Phonetic change without phonemic change Why do languages have phonological rules? The explanation is historical: languages constantly undergo phonetic changes, and these have cumulative effects upon the system. Minimally, phonetic change causes dialect differences; further changes cause systemic alterations— allophones added or lost, forcing restructuring of the sound system. Periodic restructuring accounts for language divergence, e.g. Latin evolved into modern Italian. Minimally, phonetic changes cause dialect differences, also called allophonic rules. This is what the textbook means by the phrase: “Phonetic change without phonemic change.” For example, the Scottish /r/ is the same as the North American /r/ except for one small and—some might say— linguistically “insignificant” detail: it is pronounced differently. The explanation is historical. Every pronunciation difference between two dialects is the result of phonetic change. This fact raises two questions: Which dialect is more conservative (with respect to this one comparison)? Which dialect is more innovative (with respect to this one comparison)? Scottish trilled /r/ is conservative; North American /r/ is innovative. Logically, of course, it is possible that neither dialect is conservative, because both are innovative. This idea was introduced by Sir William Jones about the relationship of Latin, Greek and Sanskrit. Phonetic change can also lead to structural changes, in 5 ways. 2. Phonemic loss 3. Phonemic addition Rephonemicization 4. shifts 5. mergers 6. splits Crowleyan Howlers On p. 74 Crowley says that “Phonemic loss is self- explanatory” and on the same page he says “Phonemic addition is also self-explanatory.” In my personal experience, any sentence I have ever read containing the word “phoneme” or “phonemic” is not selfexplanatory. Crowley’s discussion on p. 74 is clear and accurate; you may judge for yourself whether it is self-explanatory. Phonemic loss can be partial or total. Small phonetic changes can, over time, alter the phonological system. For example, the inventory of phonemes can be reduced through total loss of all allophones of a phoneme. Thus Motu was described in Chapter 2 as having lost the velar nasal via unconditioned change: *ŋ > Ø. This change altered the inventory of phonemes, reducing it by one phoneme. Phonemic loss can be partial. Much more common is partial loss of a phoneme, meaning that an allophone disappeared. For example, in Rejang, final *-l disappeared in all native words: *l > Ø/__#. Elsewhere, /l/ was retained. More radically, in many Oceanic languages, all final consonants disappeared: *C > Ø/__#. For each such language, every consonant phoneme lost one allophone. NEVER FORGET: “PHONEMES CHANGE (ONE ALLOPHONE AT A TIME)” A phoneme is a bunch of allophones—up to ten or more. Partial loss of a phoneme means one allophone disappears, e.g. word-initially. The inventory of phonemes is unaffected. Total loss of a phoneme means all allophones of a phoneme disappear. In this case, the inventory of phonemes is affected—it has been reduced by one. PHONEMIC ADDITION Again, phonemic addition can be partial or total. Partial phonemic addition means a new allophone is added; this does not alter the inventory of phonemes. Total phonemic addition means that a new phoneme is added, increasing the number of phonemes in the system. Prothesis means adding a sound at the beginning of a word. It may or may not add a new phoneme to a language. Motu added a new phoneme /l/ before word-initial /a/: Ø > l /#__a. Before the change, /l/ did not exist in Motu, so this change added a new phoneme to the language. Rejang added a new allophone [ɂ] before word-initial vowels: Ø >Ɂ /#__V. Before the change, Rejang already had glottal stop between vowels and word-finally, so this change did not add a new phoneme to the language. Amazingly, prothesis may occur without adding either a phoneme or an allophone. Does Crowley really think this is self-explanatory? Crowley’s example is Mpakwithi (N. Australia) which adds a prothetic schwa before word-initial fricatives and /r/: Ø > ə / #___ fricative r Crazy as it may sound, since Mpakwithi does not have a schwa phoneme, it cannot have a schwa allophone. Therefore, this change just “hangs out there” phonemically. It is an example of phonetic change without phonemic change. I’ll admit it The Rejang and Mpakwithi examples might make you think that linguists have lost their minds. Actually, it is only synchronic linguists that get all tangled up like this. Notice how easy and natural the phenomena are when viewed simply as sound changes. PHONETIC DETAIL PERVADES THROUGHOUT Don’t think this is as an isolated example. American speech is filled with sounds that never make it to allophonic status. For example most Southern American dialects are like Rejang in that a glottal stop is added before any word beginning with a vowel: Ø >Ɂ /#__V. In most Southern American dialects a glottal stop is added before every word beginning with a vowel: Ø >Ɂ /#__V. This change has a profound effect on the distribution of allophones of /r/. Consider the distribution of /r/ between Boston and Atlanta in the sentence: Park your car in HarvardYard. Glottal stop is added before every word beginning with a vowel: Ø >Ɂ /#__V. (Let h represent deleted /r/.) Boston: Pahk yoah car in Hahvahd Yahd. Atlanta: Pahk yoah cah ɂin Hahvahd Yahd. Both Boston and Atlanta have a rule dropping /r/ before a consonant. In Boston, /r/ occurs between two vowels in the phrase car in (with smooth onset for in); by contrast, in Atlanta the sequence is pronounced cah ɂin (with glottal onset preceding in), in perfect conformity with the rule. This chapter discusses six topics. Rephonemicization 4. shifts 5. mergers 6. splits These constitute 90% of Historical Phonology. These topices are not—repeat not—self-explanatory. THE IDENTIFICATION OF A SHIFT, MERGER OR SPLIT DEPENDS ON THE EFFECT ON THE LANGUAGE SYSTEM. Shift: When a series of phonemes change positions without affecting the number of phonemes in the system, e.g. Grimm’s Law and the Great Vowel Shift. The most famous shifts are so profound one might be surprized at the lack of mergers and splits, which would have resulted in loss or addition of phonemes. Instead, the phonemes simply got shifted around inside the articulatory quadrangle, in a series of movements called a “chain shift”. Famous Chain Shifts Grimm’s Law (Germanic) Second Consonant Shift (Germanic) Great Vowel Shift (English, 1400-1600) Note: Chaucer was born in 1400 and Shakespeare died in 1619. Northern Cities Shift (American English, 1950 - present) English represents older Germanic English and the Low German languages-Dutch, Flemish, and Plattdeutsch differ from Modern Standard German partly because Standard German has undergone a second or High German Consonant Shift. English preserves the older common Germanic sounds which were changed in High German between the sixth and the eighth centuries. Below are some English and High German cognates that show sound correspondence according to the Second Consonant Shift. A SHIFT NEED NOT ALTER THE NUMBER OF PHONEMES IN THE SYSTEM. SEE AND HEAR THE GVS http://facweb.furman.edu/~mmenzer/gvs/seehear.htm Merger Mergers in American English Don/Dawn merge in many dialects of American English. pin / pen merge / __n in South Midlands (Athens) and most of the South. MERGER As you might guess, a merger can be partial or total. Partial mergers are the most common; the allophones of two or more phonemes merge, e.g. C > ɂ / ___# (all word-final consonants became glottal stop in Minangkabau (Sumatra)). The phonemic inventory was unchanged. Total mergers also occur, e.g. Mentŭ, in Sarawak, Borneo, where *l and *r merged as *r. This change altered the phonemic inventory of Mentŭ, which now lacks /l/. Splits Split For a phonemic split to occur there must be two factors in play. a) A phoneme X undergoes a conditioned change: X > Z /A__B b) Z (and X) are phonemes in the language. Suppose there is a change n > m /__p, as in English: *in+possible > impossible. It can be said that /n/ has undergone partial split, because one allophone became /m/ while the rest remained /n/. Split of *a /__# in Rejang Rejang underwent a three-way split under complex conditions: *a o ə əy *kena > kəno *ita > itə *mata > matəy ‘strike’ ‘we (incl)’ ‘eye’ PHONEMIC CHANGE WITHOUT PHONETIC CHANGE Watch out for linguist-speak. Don’t be taken in by the smooth talk. Broadly speaking, what the above implies is impossible. But speaking very narrowly, Crowley means that a sound can be re-classified without ITSELF undergoing any change. The re-phonemicization change may simply occur elsewhere in the language. Consider what happens to the books in the library. In a local library, Book A was displayed in a section called “Young Adult” and Book B was displayed under “Adult Fiction”. Some parents complained that “Adult Fiction” sounded like dirty books, which they weren’t. Nevertheless, to avoid confusion the Library changed the display to read: “Young Adult” and “New Fiction”. In this way, the books were re-classified without any change in the books themselves. Consider how /ŋ/ became a phoneme of English. Step 1: OE had disyllables like /singe/ [siŋge]. Step 2: Middle English lost final -e by apocope, causing words to acquire a final CC: /sing/ [siŋg]. Step 3: Modern English simplified the consonant cluster by dropping the final -g, but kept the velar pronunciation of the nasal: /siŋ/. Step 4: Linguists recognized/ŋ/ as a new phoneme with a limited distribution (cannot begin a syllable). Psycholinguistic test What is your aptitude for learning Tagalog? ŋunit ‘now’ ŋaŋa ‘gape’ ŋumaŋaŋa ‘chew thoroughly’ [ŋu.ma.ŋá.ŋa] End of Chapter Four Historical Linguistics Winter 2009